Contributed by John Bergman-McCool

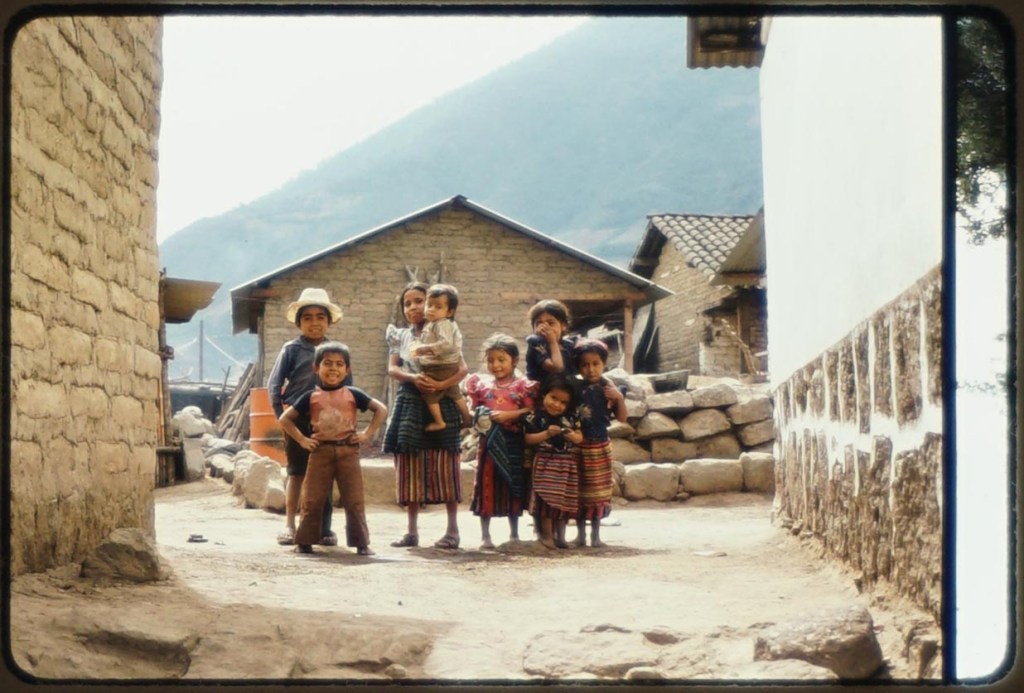

We are pleased to announce that the Peabody has installed an interactive artwork by Jonny Yates (aka Jonny White Bull). Jonny is a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and lives in McLaughlin, South Dakota. He is a talented jewelry maker, stylist, and chef, known for his own version of burger dogs, nachos with homemade chips, and other delicacies.

The piece, titled lalá, or grandfather, in the Lakota language, is a reference to Jonny’s ancestor Sitting Bull, who is depicted here. Jonny is the consummate “maker,” who loves creating carved and painted bone jewelry, drawings, and three-dimensional pieces made from cardboard, milk jugs, and other found materials.

Jonny invites everyone to spin his kinetic artwork and reflect on your own ancestors. You can find lalá in the Hornblower Gallery on the first floor of the Peabody.

CONTEMPORARY ART AT THE PEABODY

Jonny Yate’s piece joins a small but growing collection of contemporary Native art at the Peabody. When possible, the Peabody has purchased and commissioned artwork from Native artists with the support of donors and members of the Peabody Advisory Community. Artists with work in the collection include Dominique Toya, Maxine Toya, Bessie Yepa, Jeremy Frey, and Jason Garcia. These artists highlight some of the unique relationships that have developed between the Peabody and Native artists over the years. As an example, the Andover community has been fortunate to have several visits by Pueblo potters Dominique, Maxine, and Mia Toya over the years. During these visits, the Toyas share traditional pottery methods with students in Thayer Zaeder’s ceramics classes. They are very talented artists and quite passionate educators. You can read more about their most recent visit here.

THE INSTALL

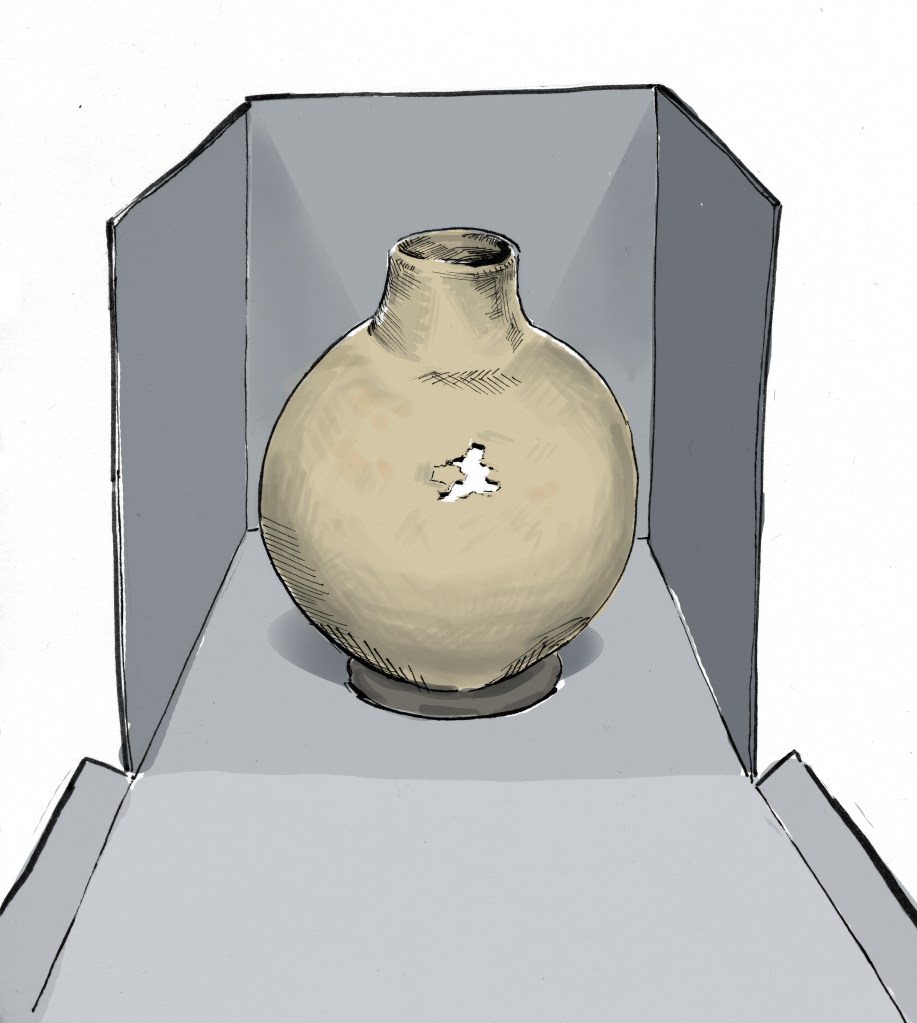

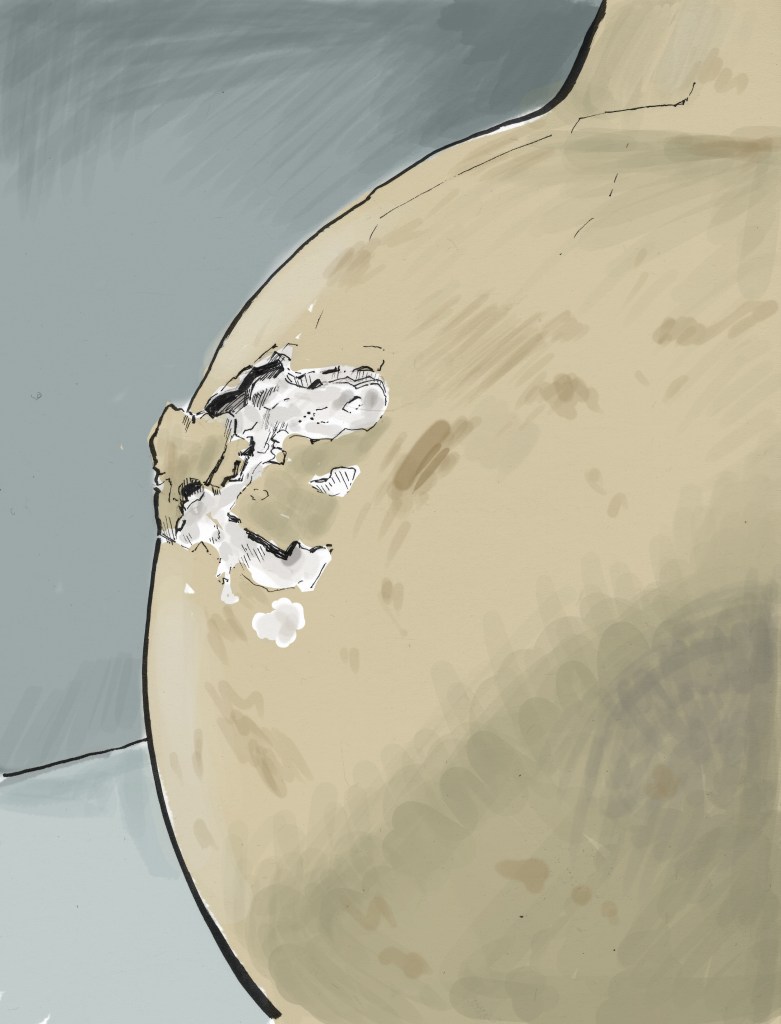

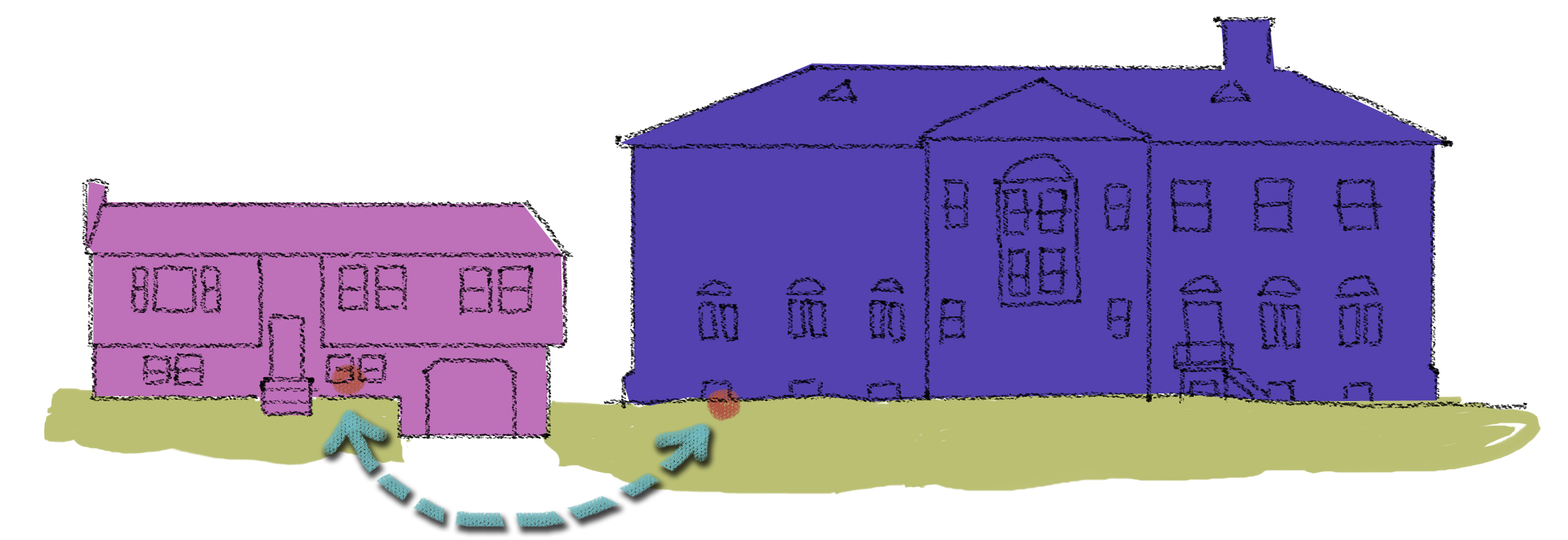

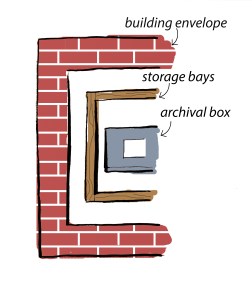

Hanging Jonny’s kinetic artwork presented a unique challenge; how could we make the piece available for a hands-on experience for students and visitors while keeping it safely installed. Research institutions, such as the Peabody, do not normally put collections on display, so we carefully considered our options. We chose to use cleats to secure the piece to the wall and a makeshift security clip to keep the piece from sliding out of the cleat. In place of a detailed narrative of the installation process, here are a series of photos of how we chose to approach the process. We hope you come by sometime and experience it for yourself.