My job is pretty amazing. I get to do what I like to do, in an institution I like with many people whose company I enjoy. What else could anyone really ask for when it comes to their career, right? Well, a job wouldn’t be a job without at least one thorn in one’s side, and here, that thorn for me is whatever the heck the people who worked here in the 1940s and 1950s were doing.

Going through the collections to complete portions of the inventory project is usually pretty straightforward. Pick a drawer, take inventory, put the information in the database, rehouse the artifacts, return the box to its location. Repeat, repeat, repeat. This is all fine and dandy until you are entering the artifact number in the database and this lovely message pops up on the screen.

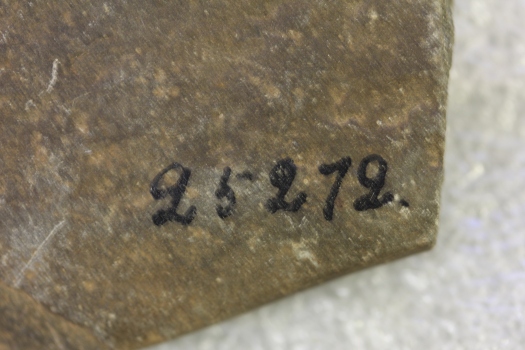

That’s right. Apparently this number already exists elsewhere in the collection. We’re just going to double check it though. After all, some of the numbers written on the artifacts are notoriously difficult to read (here’s a big shout out to whoever thought it was a great idea to loop the hook of a 2 so it looks like a 9. Or a Q. They don’t call them terrible twos for nothing).

Next step is to go to the location of where the artifact is in the database, and there it is, plain as day. These two artifacts have the same number and are housed in very different locations from each other. Okay fine, no big deal. We’ll just update the catalog record to say that there’s another artifact with this number in this location. Right? RIGHT?!

Now, there are times when this makes sense. Maybe someone took an object out and forgot where they got it from and just made their best guess when they put it back. However, when it comes to artifacts from Northern Maine, I have absolutely no idea what people were thinking. Some objects with the same number are spread out between four or five different drawers. Typically, it is ceramics that have recieved this inhumane treatment. My best guess is that someone attempted to separate the ceramics out by design motif for analysis. One motif is housed in a box, regardless of what object numbers the sherds have, another motif in a different box, so on and so forth. In a way this would make sense. It would make even more sense if the motifs were ACTUALLY the same. However, more often than not, the design patterns are not really the same at all. A few sherds may have a similar decorative pattern on them, while many sherds look so vastly different that I have to question what they were looking at. This practice makes the inventory process particularly difficult when there are sherds with four different object numbers in a box along with dozens of sherds with no number whatsoever. It therefore becomes impossible to determine which sherd belongs with which object ID number, and as a result, all of the unnumbered sherds are assigned a “found in collections” number.

What I have learned through this process is that we must improve on the housing methods of the past. I shudder to think that someone in the future will go through the collections and question what the heck I was doing and silently curse me under their breath. Extreme organization is a key to happy collections and happy employees/volunteers of the future, and I truly hope that some of the organizational methods that have been implemented during my time here help to achieve this goal.