Contributed by Ryan Wheeler

Poster sessions are a great way to share information and connect with people at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology. Exhibitors have two hours to share their research and projects, connecting at length with attendees that stop by to chat–a bit less pressure than the regular sessions and symposia! At the recent 89th annual meeting of the SAA, the Journal of Archaeology & Education was represented at the Thursday afternoon posters after hours session. For those that couldn’t make it, here are some highlights of our poster:

Abstract

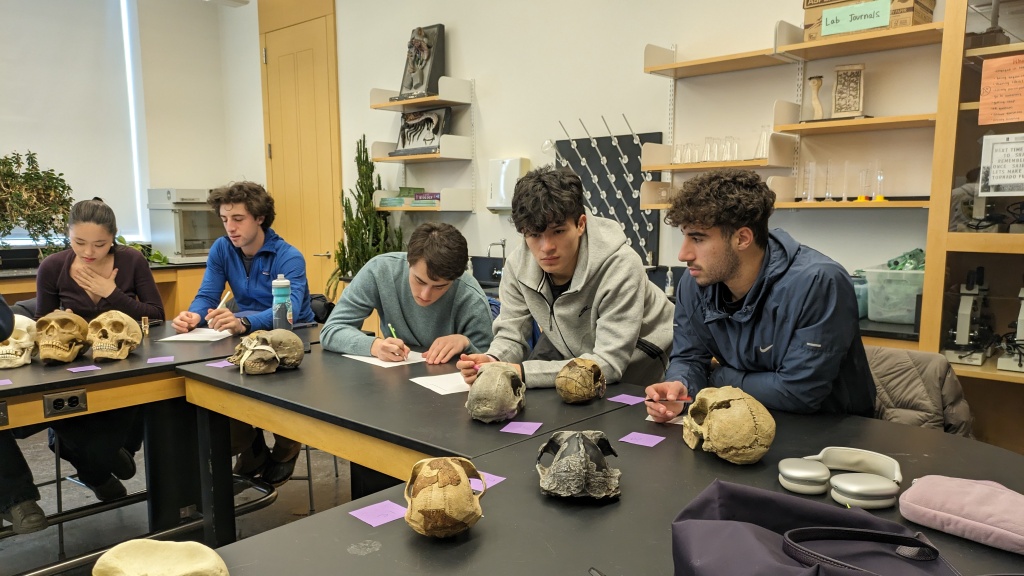

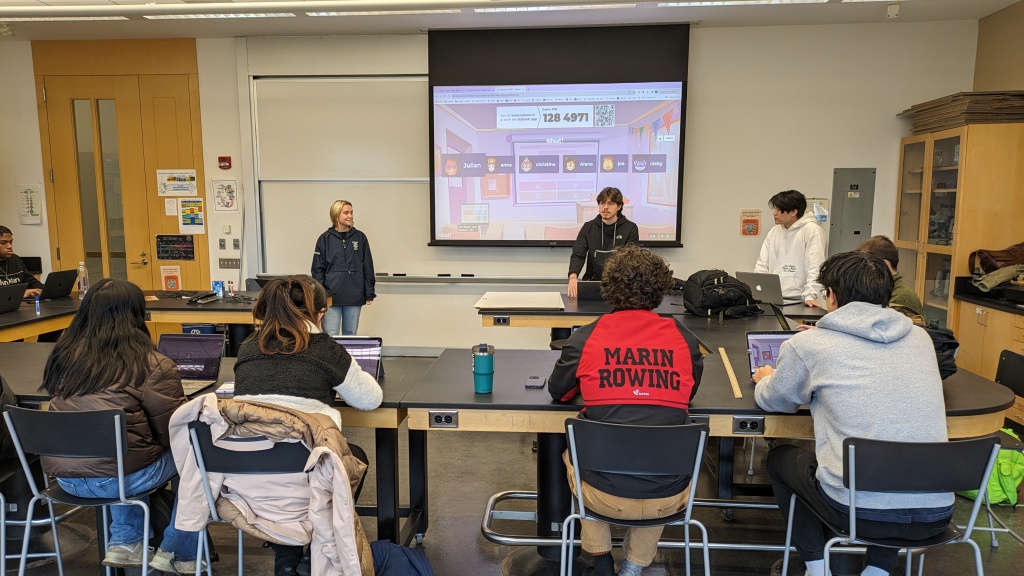

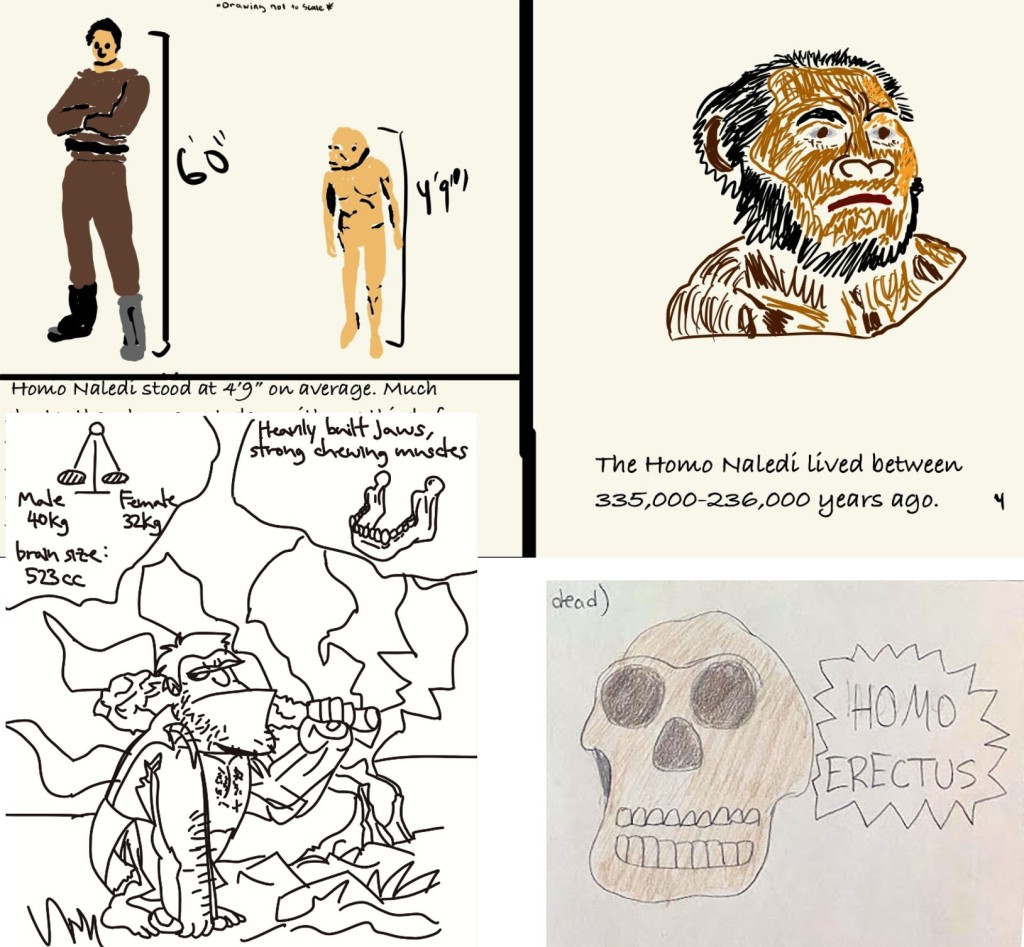

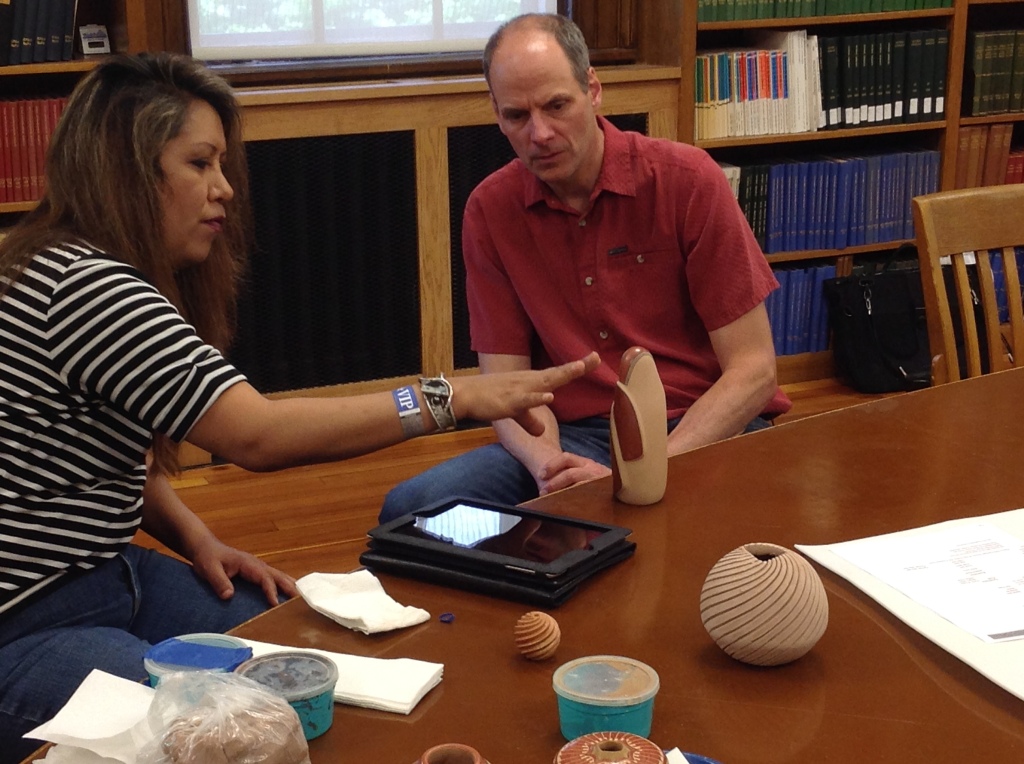

Education has become an important component of archaeology in all realms, from traditional teaching arenas in universities and K-12 schools to research to government and contract work. In 2017 the Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology and the University of Maine, Orono collaborated to found the Journal of Archaeology & Education, a peer-reviewed, open-access journal dedicated to disseminating research and sharing practices in archaeological education. The journal’s founders recognize the significant role that archaeology can play in education at all levels and intend for JAE to provide a home for the growing community of practitioners and scholars interested in sharing their first-hand experiences and research. Since 2017, JAE has published 41 articles and 2 special issues with a total of 12,412 downloads. JAE’s editorial board contend with issues around growing awareness and increasing submissions, as well as how to handle the ethics of human subjects research in environments where Institutional Research Boards are not always available and researchers are not consistently aware of the need to have their research vetted.

About the Journal

The Journal of Archaeology and Education is a peer-reviewed, open-access journal dedicated to disseminating research and sharing practices in archaeological education at all levels. We welcome submissions dealing with education in its widest sense, both in and out of the classroom—from early childhood through the graduate level—including public outreach from museums and other institutions, as well as professional development for the anthropologist and archaeologist.

The journal’s founders recognize the significant role that archaeology can play in education at all levels and intend for the Journal of Archaeology and Education to provide a home for the growing community of practitioners and scholars interested in sharing their first-hand experiences and research. Costs related to publication are shared by the University of Maine, providing for access to the bepress publishing platform, and the Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology, funding copyediting and layout. Authors are not assessed any fees.

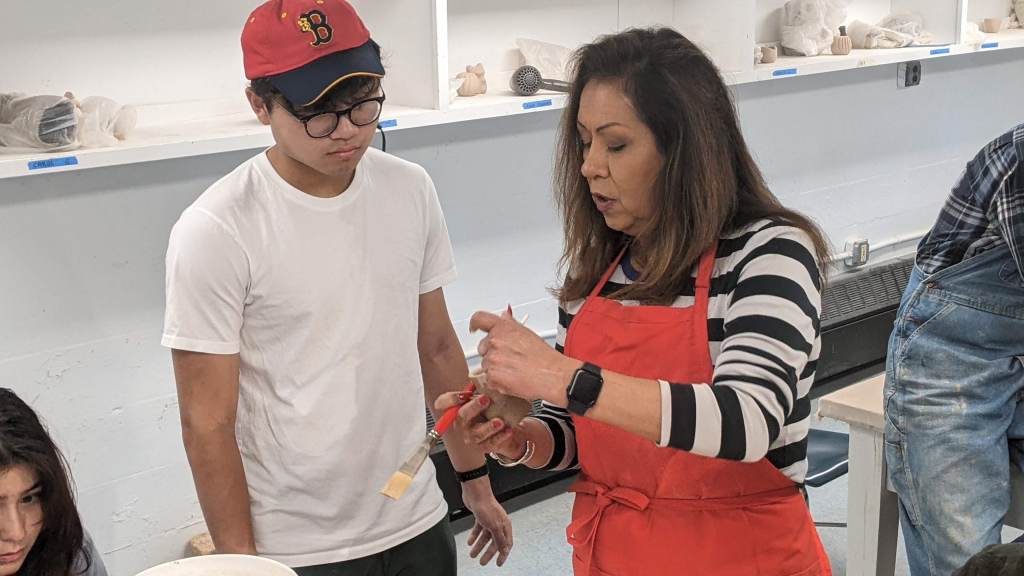

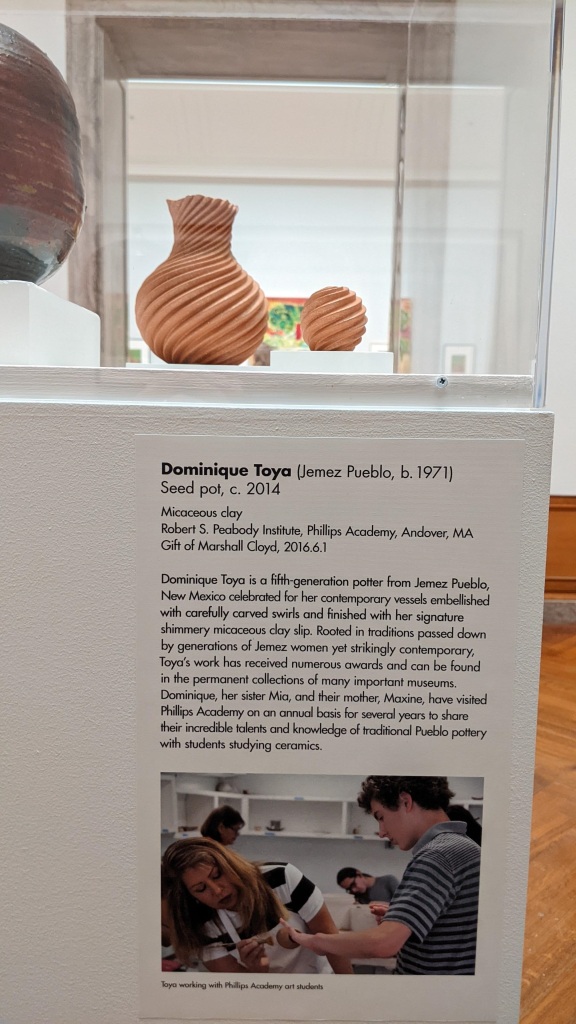

The journal was founded at the Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology, where archaeology is used to support high school curricula at Phillips Academy, and is hosted at the University of Maine’s Digital Commons website. Contact the editors by emailing Kathryn Kamp (KAMP@Grinnell.EDU) or Ryan Wheeler (rwheeler@andover.edu).

Open Access Publishing

Open access publishing has significantly increased since 2010, when only around 30% of all articles published were freely available, to about 50% of articles published in 2019 (Heidbach et al. 2022). The overall trend has been toward open access publishing, as governments in both Europe and North America have pushed for open access publishing of studies that they have funded. The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) currently indexes 180 open access archaeology journals. Different levels of open access publishing include Gold, where all a journal’s articles are open access and indexed by the DOAJ. Often this requires that the author pay an article processing fee. Green level involves reader payment on a publisher’s website, but articles may become more freely available on open access archives after an embargo period. Hybrid level allows authors to choose from the Gold or Green open access models. Bronze level open access sees publication in a subscription-based journal (see Greussing et al. 2020; Marwick 2020). Other models–sometimes referred to as Diamond or Platinum–omit fees for authors and readers, like the JAE approach. Almost all of the open access models include some fees by either the author or reader, and this has become a significant discussion in open access publishing and academic publishing in general. Initially these fees were expected to be rather low, but now author fees are regularly thousands of dollars. This is an obstacle to those publishing studies that are adjacent to their primary research (often the case with archaeology education studies), or those working in areas with limited funding. Marwick (2020) uses the hashtag #openirony to describe articles published on open access in archaeological publishing that are, in fact, unavailable to many readers due to paywalls.

IRB Policy

In 2021, the JAE adopted a requirement for Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, or equivalent, for articles involving human subjects. The Editors and Editorial Board found that many archaeologists were unfamiliar with IRB review, but as they conducted and published assessment research, such review involving students and program participants was necessary. The policy states:

All human subjects research results published by the Journal of Archaeology and Education (JAE) must be approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or an equivalent entity in the author’s country. The purpose of IRB review is to assure, both in advance and by periodic review, that appropriate steps are taken to protect the rights and welfare of people participating as subjects in your research. If you do not have an IRB affiliated with your organization, you must find a suitable IRB at a qualified university or other institution. Most universities have IRBs that will accept applications from outside their institution. Authors, especially those without an academic affiliation, could use an independent IRB, which is subject to the same federal regulations as universities. There may be fees associated with university and independent IRB reviews. The IRB protocol number assigned by your IRB must be included in the article. Manuscripts without IRB approval will not be considered for publication in JAE.

Top Articles

AE has published 41 articles to date, with 12,412 downloads and 9,897 abstract views. Top referrers are http://www.google.com and scholar.google.com, followed by the JAE website and individual articles. Top articles, based on daily downloads, are listed below:

Future of JAE

JAE continues to solicit manuscripts for single articles and special focus issues. We anticipate an application for inclusion in the Directory of Open Access Journals this year, following initial notes from DOAJ to be clearer about author rights and licenses. Challenges include increasing manuscript submissions, identifying reviewers, and competition from more prestigious journals. Bocanegra-Valle (2017) discusses the challenges faced by “emerging” open access journals like JAE and outlines best practices for developing credibility in the academy. We believe that offering a publishing outlet without author or user fees, especially at the intersection of archaeology and education, remains critical for fostering community, especially when most archaeology education research is not supported by significant grant funds that could be used to pay author fees. Also, we are interested in input from authors and readers; for example would it be good to have a short submission option for practical teaching suggestions and actual exercises? What about reviews of films or web resources? We welcome your suggestions!

References Cited

Ana Bocanegra-Valle (2017) How Credible Are Open Access Emerging Journals?: A Situational Analysis in the Humanities. In Publishing Research in English as an Additional Language: Practices, Pathways and Potentials, edited by Margaret Cargill and Sally Burgess, 121–50. University of Adelaide Press, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.20851/j.ctt1t305cq.12.

Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), https://doaj.org/

Esther Greussing, Stefanie Kuballa, Monika Taddicken, Mareike Schulze, Corinna Mielke, Reinhold Haux (2020) Drivers and Obstacles of Open Access Publishing. A Qualitative Investigation of Individual and Institutional Factors. Frontiers in Communication, DOI: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.587465.

Katja Heidbach, Johannes Knaus, Ingo Laut, Margit Palzenberger (2022) Long Term Global Trends in Open Access: A Data Paper. Research Information Observatory, DOI:10.17617/2.3361428.

Ben Marwick (2020) Open Access to Publications to Expand Participation in Archaeology, Norwegian Archaeological Review, DOI: 10.1080/00293652.2020.1837233.