Contributed by John Bergman-McCool

AI seems to be everywhere these days. A recent real-world example of AI creep came during this year’s Super Bowl where roughly 25% of the ads that aired were about AI or utilized AI to generate ad content. In general, the ads promised increased productivity and greater inclusion of AI in our everyday lives.

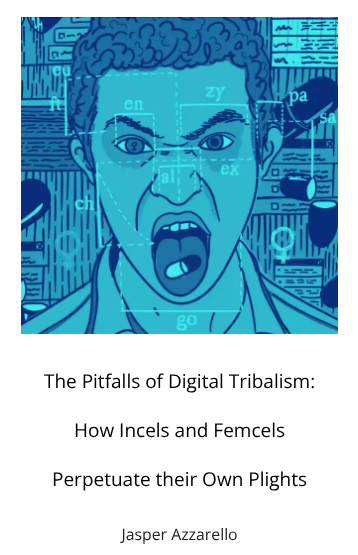

Aside from the occasional Google Lens image search, I haven’t found a productive use for artificial intelligence in my everyday life. A recent study of ChatGPT interaction logs illustrated that, by rank, people engage AI most for creative composition, “romantic” role-playing, planning, and as a source of general information. Productive uses for AI, including coding and academic composition, came in farther down the list.

In my work at the Peabody, I engage in data management tasks that are repetitive or deal with large amounts of data. I have learned to use Excel tools to make my work more efficient (VLOOKUP- if you know, you know). However, some tasks are more complicated and in recent years we have explored AI as a tool for processing them.

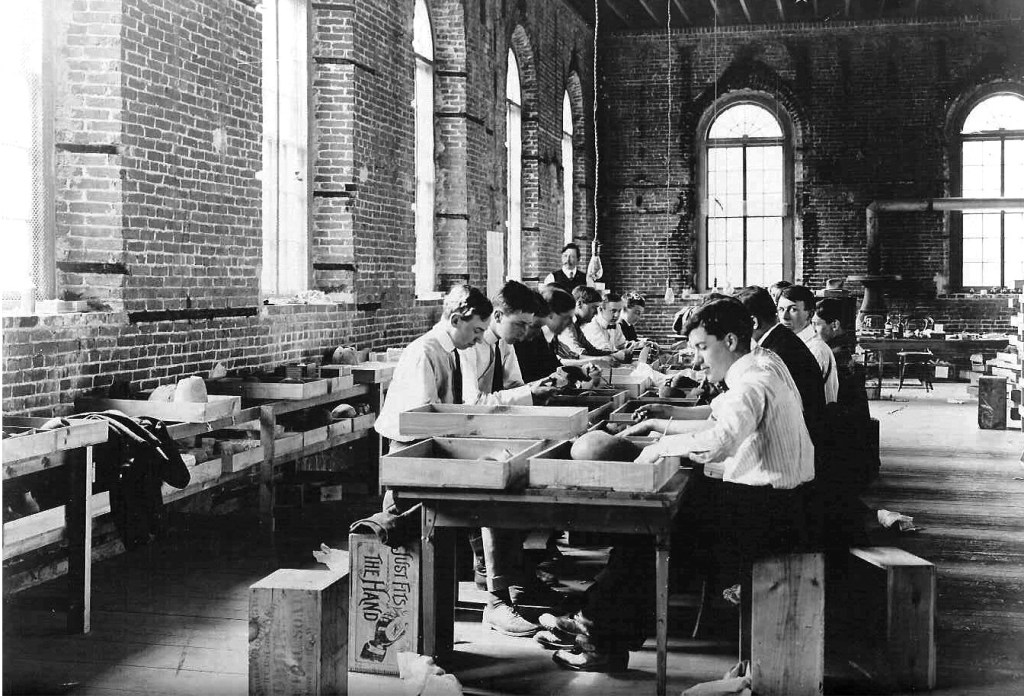

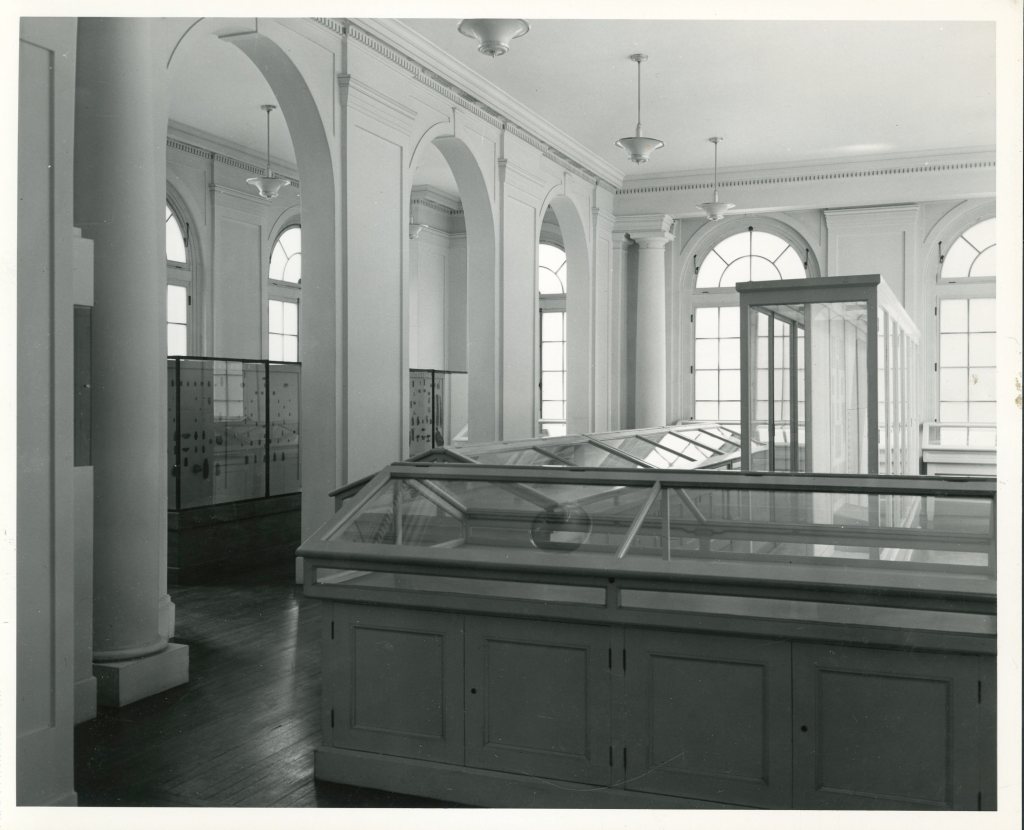

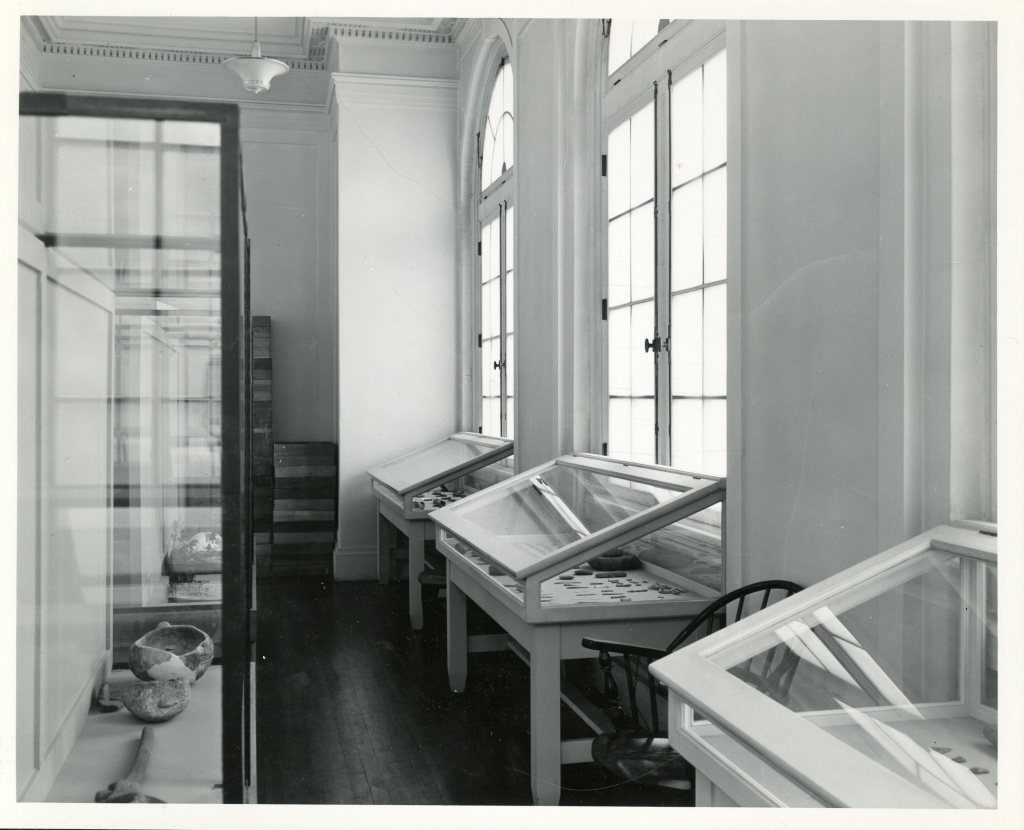

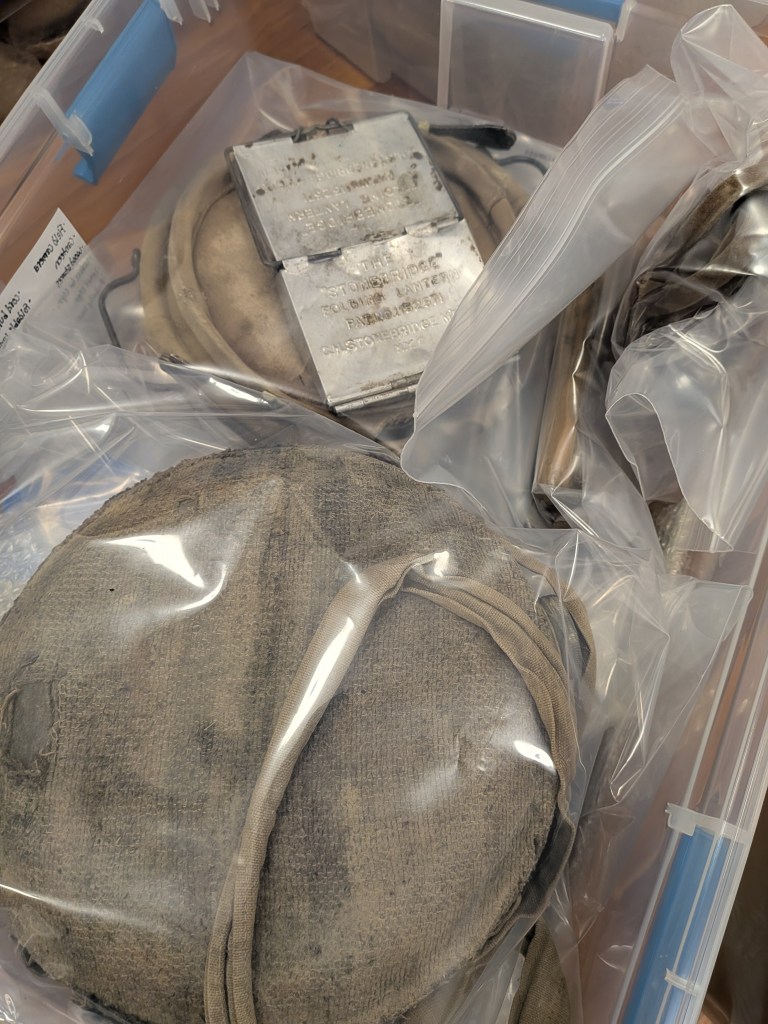

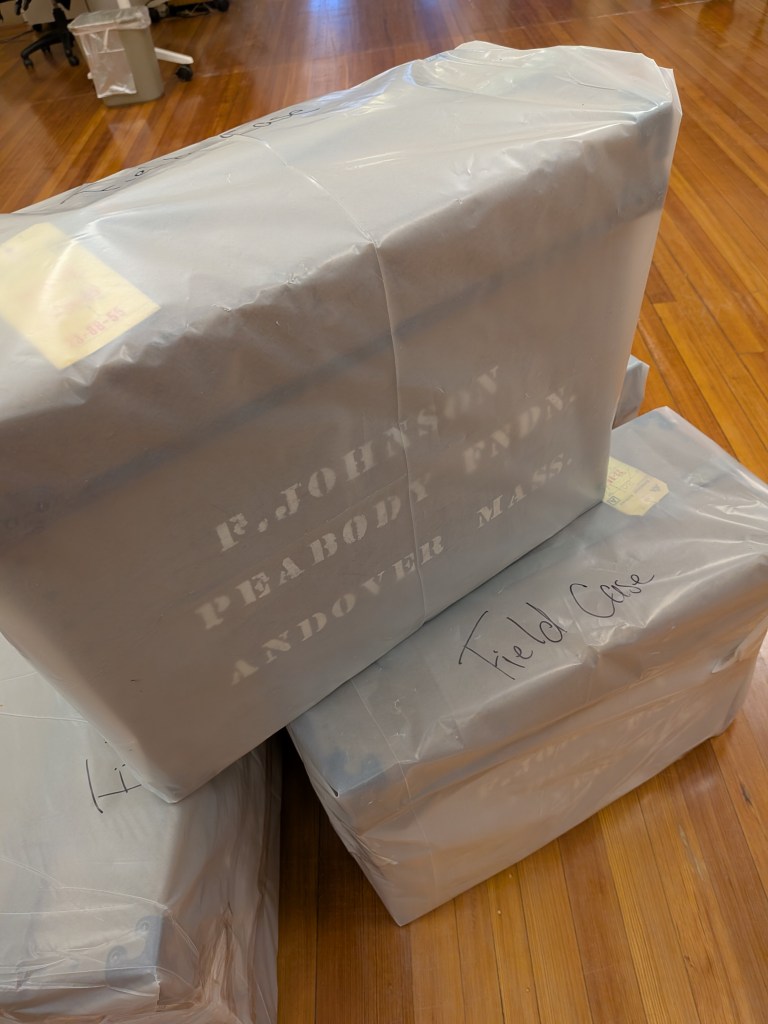

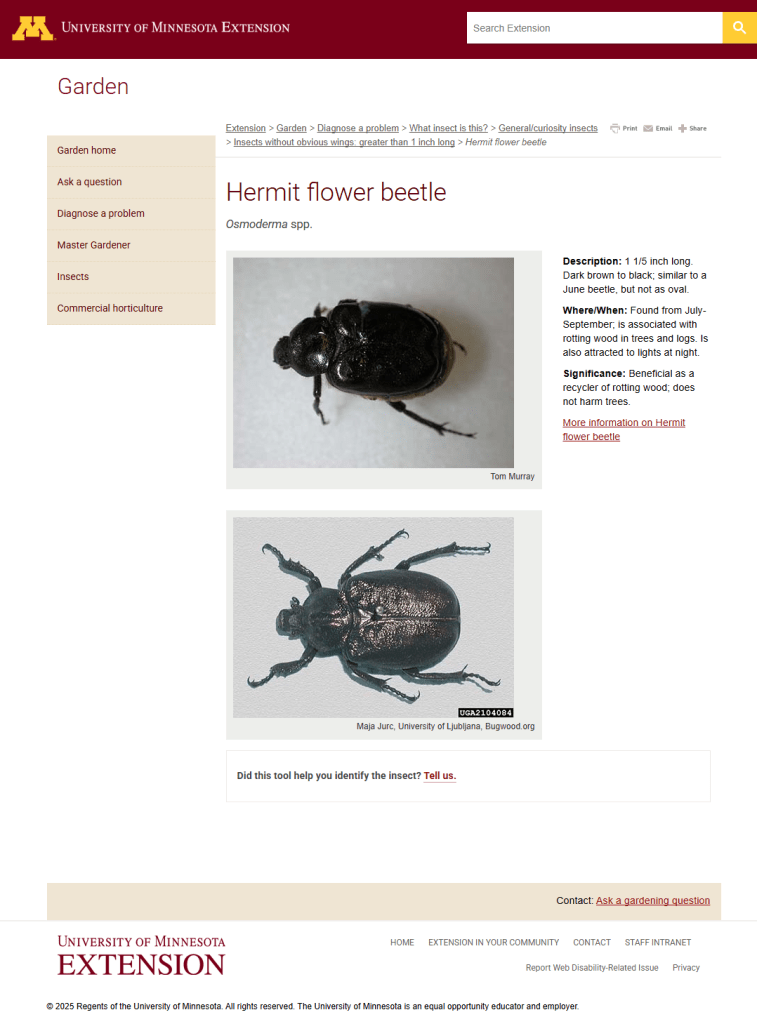

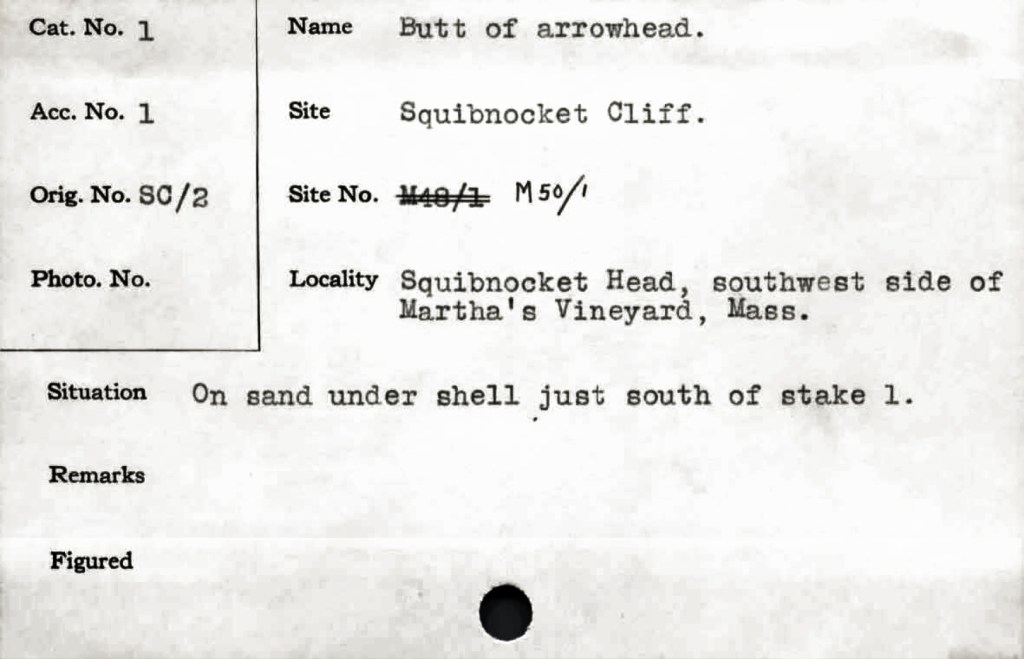

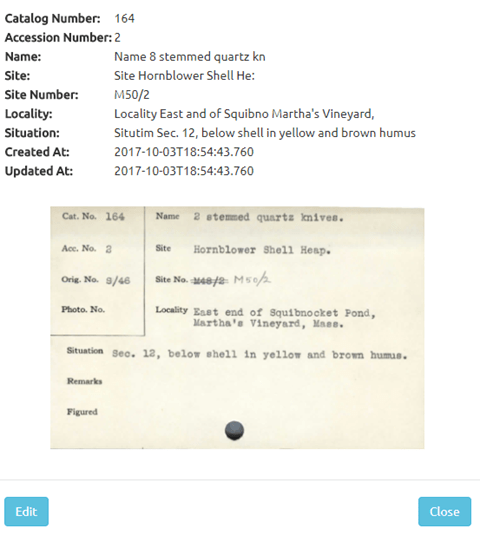

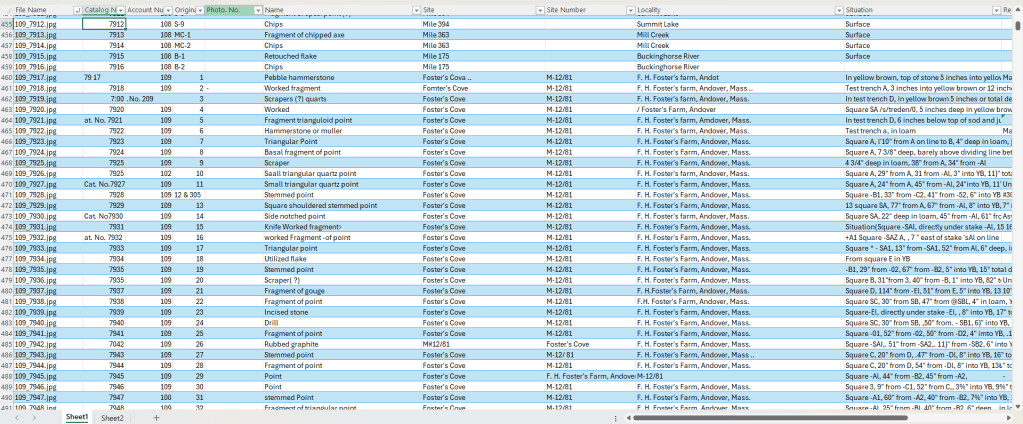

One such complicated process is transcribing institutional records. We have roughly 50,000 catalog cards that are associated with our collections that were accessioned between the 1930s and 1970s. These cards hold valuable information on provenience and provenance for our collections and should be included in our database. Extracting the text from these cards would normally require time-consuming transcription of text by hand into an excel document.

As an example, in 2019 we were awarded an Abbot Academy Fund grant to hire a temporary staff member to transcribe our handwritten accession books. The process took a little over a year and, eventually, three staff members were tasked with completing the project. By comparison, the catalog cards would likely take just as much or more time to process.

Unlike the handwritten ledgers, the typed catalog cards have the benefit of being able to be converted to searchable text through the use of Optical Character Recognition (OCR). Many of us have converted a PDF into a searchable document with OCR. The technology is standard in many PDF readers these days.

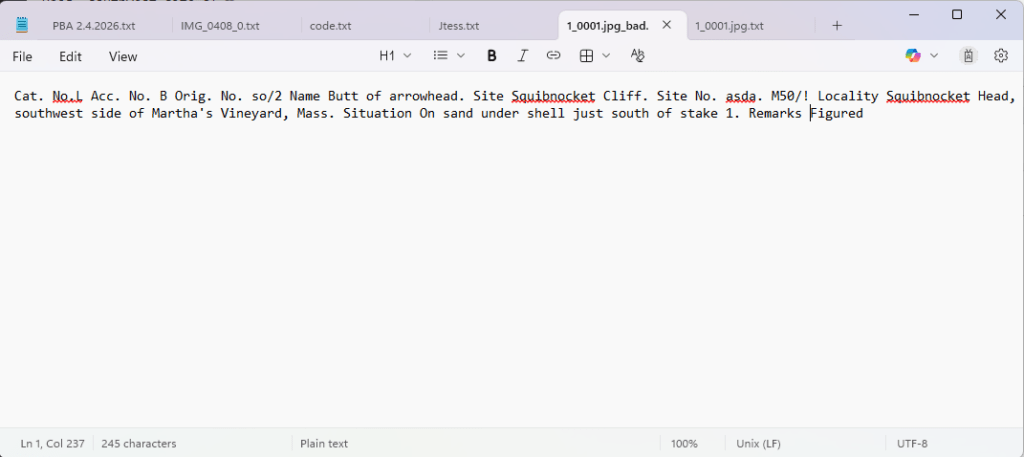

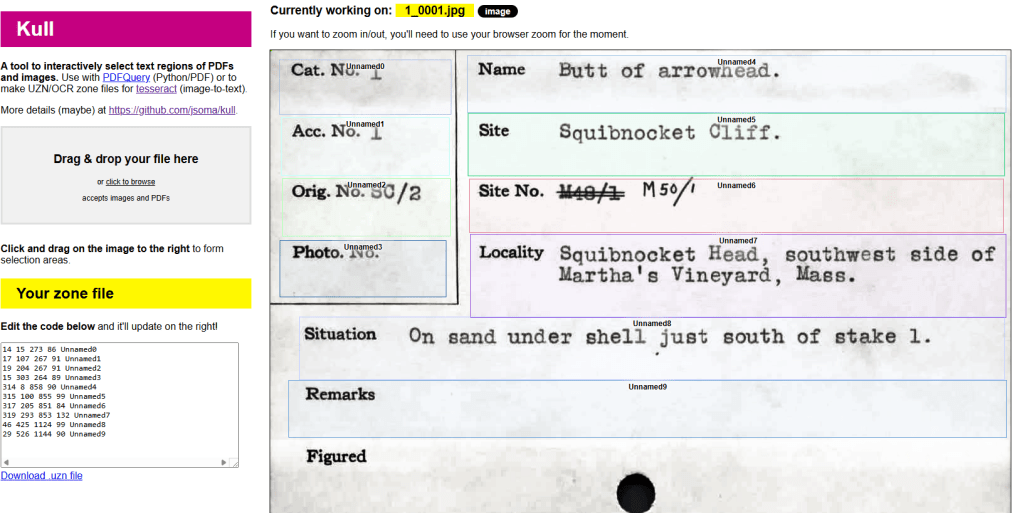

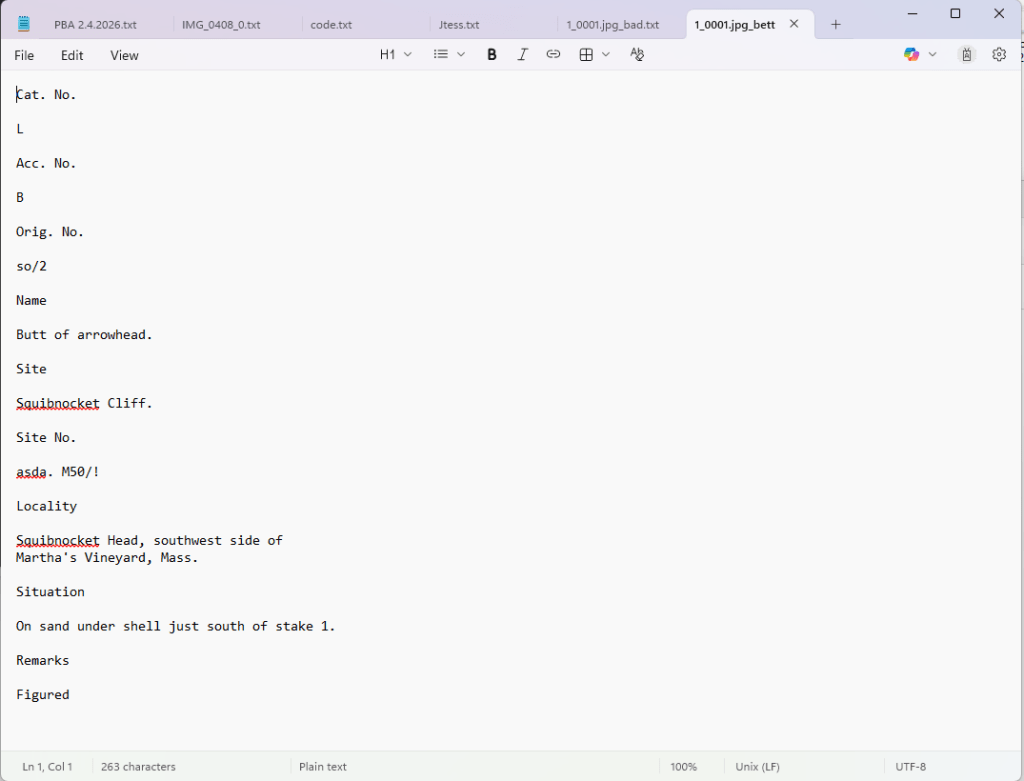

Various attempts have been made over the years to use OCR to extract the text from our catalog cards. The process is complicated because, in the case of these cards, a block of text is useless unless it can be related to the field it originated from. OCR is also an imperfect technology; it can include a lot of errors. Despite these problems, it can be helped with a bit of training.

PA students embarked on the first attempt to read and extract the catalog card data. They created a computer program which read and extracted text from the cards and placed the text in corresponding fields. Even better, their model could be trained through the use of Machine Learning thereby improving the program’s accuracy over time. OCR, on its own, utilizes pattern-recognition which does not qualify as Artificial Intelligence. Once Machine Learning was incorporated the program fell squarely within the realm of AI.

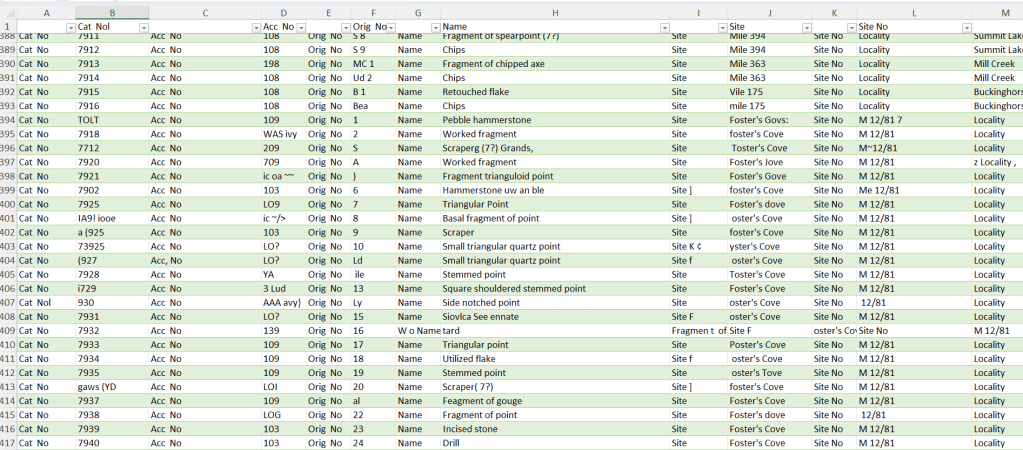

Output from the program was quality checked by humans; this was one of my weekly tasks when I first started working at the Peabody. In theory, the errors I and others corrected were fed back into the program. Once the output was loaded, the program would improve with subsequent readings.

Unfortunately, the student who spearheaded this program graduated and the project fizzled out without seeing results from the Machine Learning. Not long after, I found that I was consistently going to the catalog cards for provenience information. I realized that the project had serious benefits for our data management and I decided to take it on in my free time.

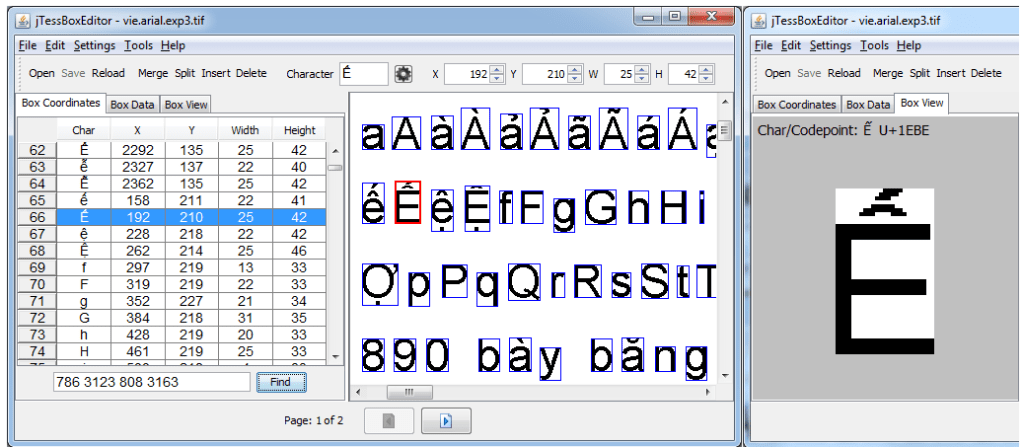

I found Tesseract OCR, a free and powerful tool for extracting text from images. I learned to use it in concert with tools to target specific areas of the cards so that the extracted text could be associated with its field of origin. The results were not great, so I learned how to improve the quality by correcting errors and feeding them back into the program. I basically recreated a very crude, inelegant and less functional version of the student program.

Early training showed that the program was probably not going to improve without a lot of input. I decided to stop working on the project at that point.

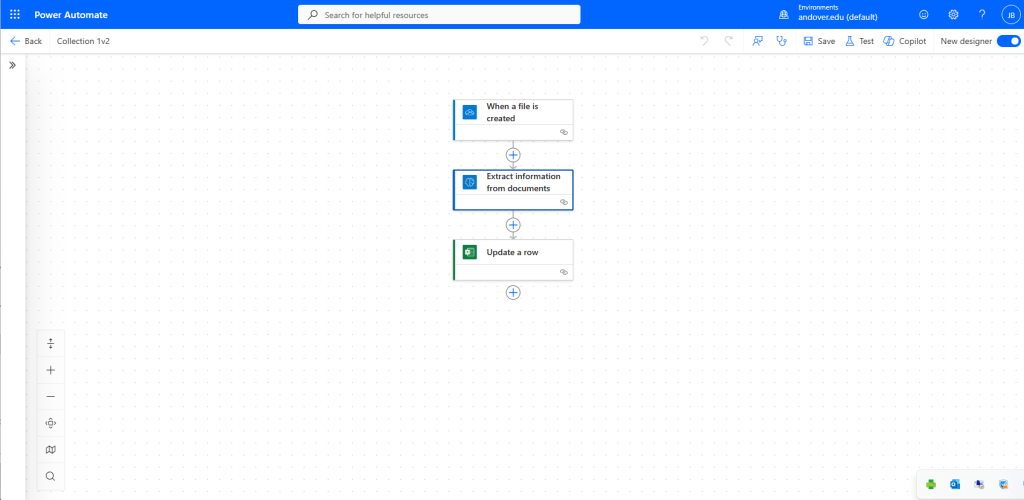

In the intervening years, AI tools have been developed that can read text with greater accuracy. We learned of a museum professional using Microsoft’s Power Automate to read catalog cards. We reached out and got a basic roadmap for how we could make the program work.

Very briefly, the AI Hub within Power Automate allows you to create a visual workflow that skips the need to write code. In addition to the workflow, I trained a model on ten examples of catalog cards. The training process allows you to select fields for the model to read. With the model trained and a workflow created, I was able to generate an Excel document where the extracted fields would be output.

The process of understanding how to set up the workflow, how to trigger it, and how to send the output into Excel were challenging. It required tinkering and several YouTube videos to get it function. It was not easy, but it was achievable, eventually.

And now, the Peabody has entered the AI age. If you need any advice on how to set up a workflow for reading documents, please feel free to reach out to me. Best of luck in your AI exploits.