Contributed by Nick Andrusin

I already did 6 years of school, what’s one more class! This summer I had the opportunity to do some professional development with the Peabody, and I was more than happy to take advantage of the chance to learn something new. Museum Study LLC is a service that offers online courses and virtual lectures on a variety of museum related topics, from collections management to administration.

Museum Study online professional development – Home

After some painful humming and hawing (I was informed I can only do one at a time…Marla…) I decided on Foundations of Community Engagement, taught by the awesome Dr. Shannyn Palmer.

Museum Study Instructor Shannyn Palmer

My background is in public history, and part of my role at the Peabody is engaging with the community, so it was a good fit. The class lasted for the month of July and was virtual. Each week involved multiple readings on how different museums have incorporated community engagement, how it’s been done successfully (or unsuccessfully in a few cases), and the philosophy behind ethical engagement with museum communities. We would have questions and assignments to fill out, and then we would meet once a week virtually to discuss what we learned. The class was small, but the conversations were interesting, with participants from a variety of museums.

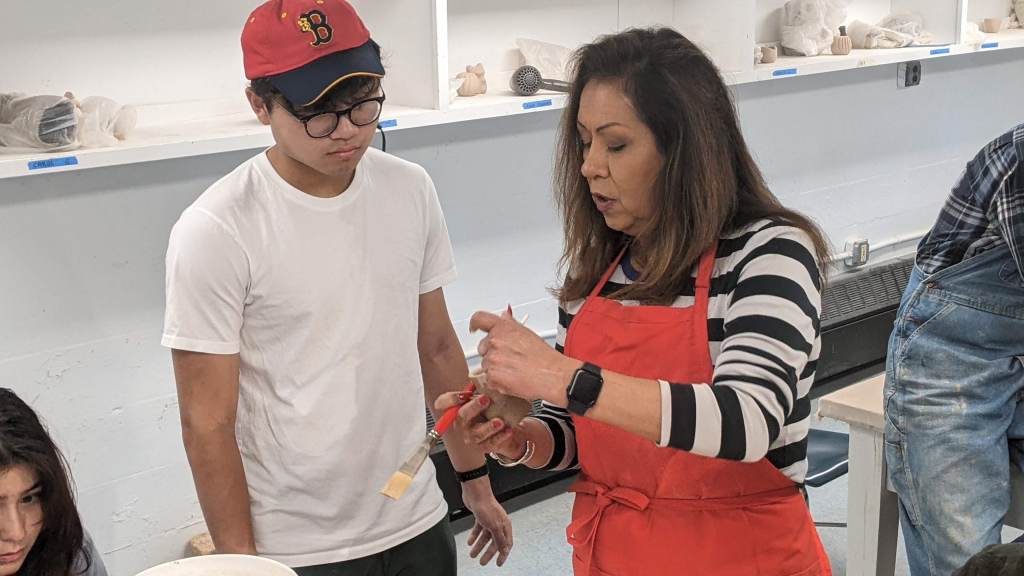

Just what is community engagement? Well, not to use a circular definition, but it’s how a museum engages with its communities. How much, what methods, which groups specifically, etc. The particulars will vary from project to project, but it all centers on connecting, collaborating, and co-creating with the group. Not just having them sign off on the project but allowing them the opportunity to be meaningfully involved in the planning and/or execution. Again, depending on the specific context of the exhibit or project. A big aspect of the class was the idea that this is not a perfect science and there is no one size fits all solution. It’s something that needs to be practiced and adapted to different situations. If a museum is doing an exhibit on a specific local community for example, that community should be involved from the outset, and at multiple levels of the project. Otherwise, what little involvement they do have may be tokenistic and the exhibit could be inauthentic or potentially offensive.

As largely public institutions, museums live and breathe on how well they engage their communities. Therefore, this engagement being ethical and non-tokenistic is a big deal. Between the modern-day ramifications of white supremacy and colonization, as well as the Covid-19 pandemic, museums are at a bit of an impasse. Questions about whom museums serve and what they should and shouldn’t do are becoming more common. Their roles are evolving as they determine their purpose. Ethical community engagement is the right way to ensure the museum is not failing the groups and individuals served.

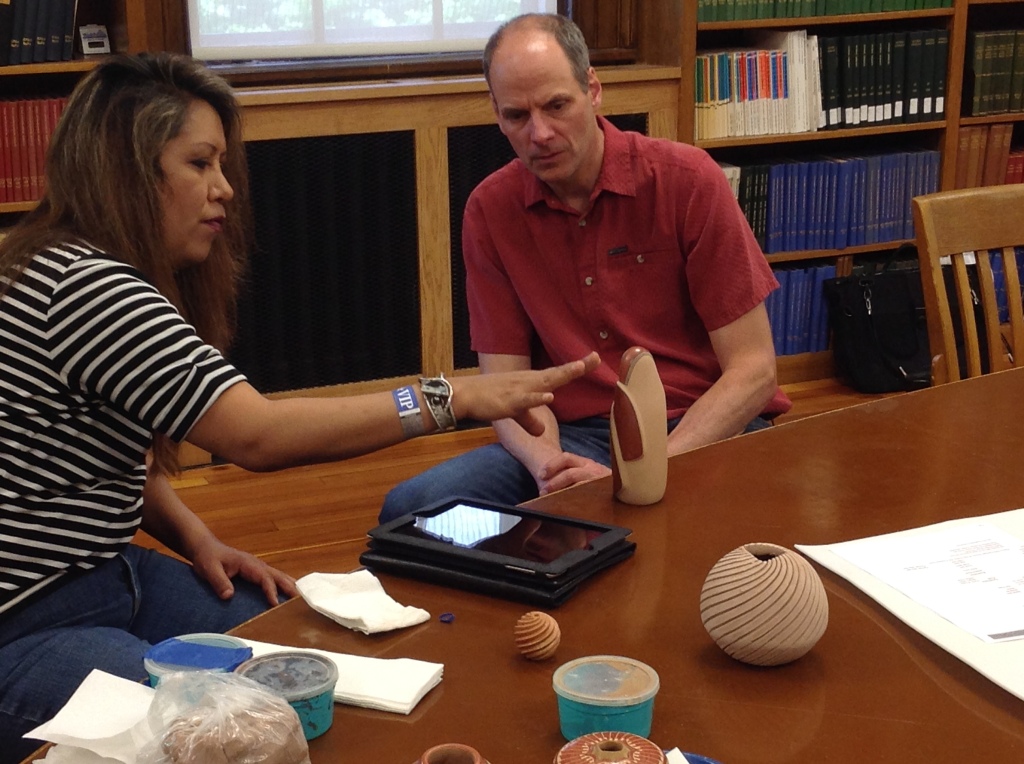

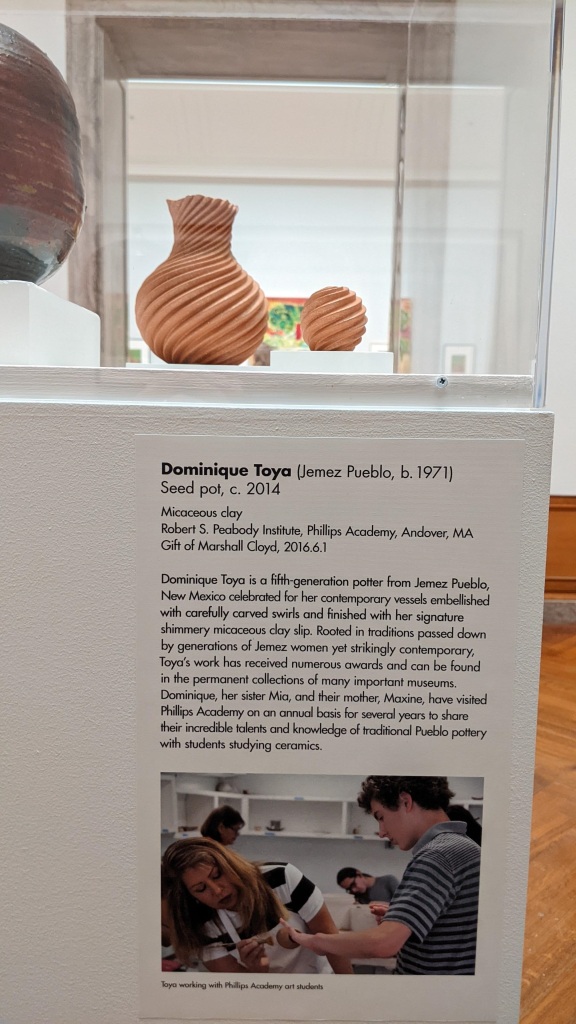

The Peabody is an interesting museum in this case, because we haven’t created exhibits for the last couple of decades. Therefore, our community doesn’t really include your typical idea of museum visitors. However, the students and faculty of Phillips Academy absolutely fit the definition of our community. As well as the Native communities we work with during repatriation. Ergo when the Peabody does community engagement, we seek to collaborate with these groups in balanced and effective ways.

Overall, it was an interesting class with a great professor! I am very grateful to the Peabody for the chance at some professional development! This was just a taste of what it offered; one blog is far too short to go into detail on everything. If I piqued your curiosity, you will just have to check out the class for yourself….