The Peabody oral history project began last year, a little by chance. I recognized the name of a family friend, retired Brandeis Anthropology professor Robert (Bob) Hunt, in some of our archival records from the Scotty MacNeish era. Peabody director Ryan Wheeler suggested I reach out to Bob and ask about his memories of MacNeish. I did, and Bob eventually came up from Cambridge to carry out the oral history in April 2017. Curator of collections Marla Taylor and I had an hour-long conversation with him, which was recorded and transcribed and is now part of our archives (and available for anyone who is interested). As it turns out, Bob and his first wife Eva Hunt met MacNeish in Mexico in the 1960s – they were doing archival research in Mexico City, and fieldwork among the Cuicatec, a small Mexican-Indian group located between the Tehuacán Valley and the Valley of Oaxaca. They crossed paths with MacNeish and his crew in the city of Tehuacán and became friends. Eva also wrote a chapter on irrigation for Volume Four of the Tehuacán publications.

It was fascinating to hear about MacNeish from someone who had known him personally and who could describe and contextualize his personality, fieldwork and scholarship. I had just spent several months processing MacNeish’s papers and welcomed the opportunity to learn something new about this person who was very familiar to me, but in a two-dimensional, removed in time sort of way. Now that I have done several oral histories, I recognize this wondrous quality while conducting them of time being suspended, of the past and present merging, as individuals and situations are evoked and memories are transmitted anew. As an archivist who usually works with static records, experiencing the living, human dimension of archives through these conversations has been very meaningful.

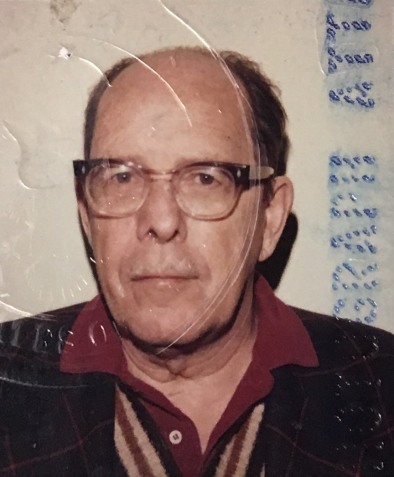

After the interview with Bob Hunt, Ryan suggested a few other people with whom he thought it would be great to do oral histories. Anticipating that some of them would be at the Society for American Archaeology conference in Washington, D.C. in April, Ryan proposed I attend too. I then arranged ahead of time to meet and carry out the interviews with Ted Stoddard, associated with the Peabody in the late 1940s-early 1950s, and with Dick Drennan, a curator at the Peabody in the 1970s. Their stories were wonderful to listen to: Ted described carrying out fieldwork in Maine for the Peabody as an undergraduate and then graduate student at Harvard, his memories of the Peabody director and curator team Doug Byers and Fred Johnson, and how he went on to pursue a career outside of archaeology. Dick talked about carrying out fieldwork in Mexico, teaching the archaeology class to Phillips Academy students and carrying out excavations at the Andover town dump, other memories of the Peabody at the time, and how the position fit into his overall career. I am still finalizing those transcripts but they will soon be available for anyone interested to consult.

I hope the oral history project will continue over the years to come!

The Temporary Archivist position is supported by a generous grant from the Oak River Foundation of Peoria, Ill. to improve the intellectual and physical control of the institute’s collections. We hope this gift will inspire others to support our work to better catalog, document, and make accessible the Peabody’s world-class collections of objects, photographs, and archival materials. If you would like information on how you can help please contact Peabody director Ryan Wheeler at rwheeler@andover.eduor 978 749 4493.