Contributed by Lainie Schultz

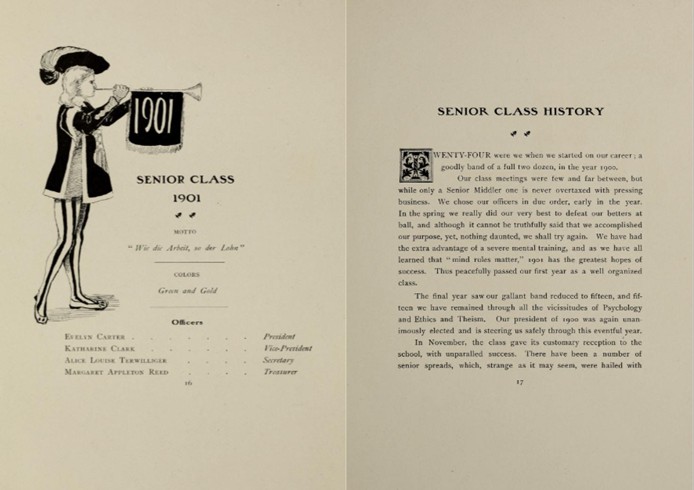

Hitting a major birthday like a 125th is no small thing. Even institutions established to preserve history in perpetuity – like, say, an archaeology museum – rarely last even a fraction of that time. The Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology reaches this milestone on March 21, and it offers a moment for introspection: how did we manage to make it this long? What has the Peabody done in that time? What from our past continues to inspire us today – whether as something we seek to sustain or that guides us toward new directions?

I hope you aren’t now looking at me to answer any of these questions. These are thoughts to let tumble around the entirety of this anniversary year, and beyond. (Possibly we should all start our quasquicentennial with a (re)reading of “Glory, Trouble, and Renaissance at the Robert S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology” – because, yes, Emma, I am fancy!).

Instead, I want to go all the way back to the beginning. If we are going to ask how far the Peabody has gone, we have to know where the Peabody started. This makes me wonder: What was the world the Peabody was born into? What did 1901 look like? With the help of Google, below is an absurdly partial snapshot of life as the Peabody came onto the scene.

[Word of warning: despite my best intentions, it turns out that when you’re doing a Google search, in English, with an internet connection in MA, and an education obtained almost entirely in the US, Canada, and Australia; and when you’re trying to find examples of events that you think will be “recognizable” and “interesting” – you end up with a pretty biased list. You would almost think from my snapshot below that the only noteworthy things to happen came out of the US and Great Britain (which I think is wrong?). Please bear in mind AAALLLLLL the other places and people and happenings not remotely referenced here while reading.]

In no particular order and with truly no claims of significance:

A lot a lot a lot of people died. Some of these deaths were noted by historians, and even the general public. These included: Queen Victoria (at the time the longest reigning monarch of Great Britain); President William McKinley (the third US sitting president to be assassinated); and Cecil Franklin Patch Bancroft (the 8th Principal of Andover’s Phillips Academy).

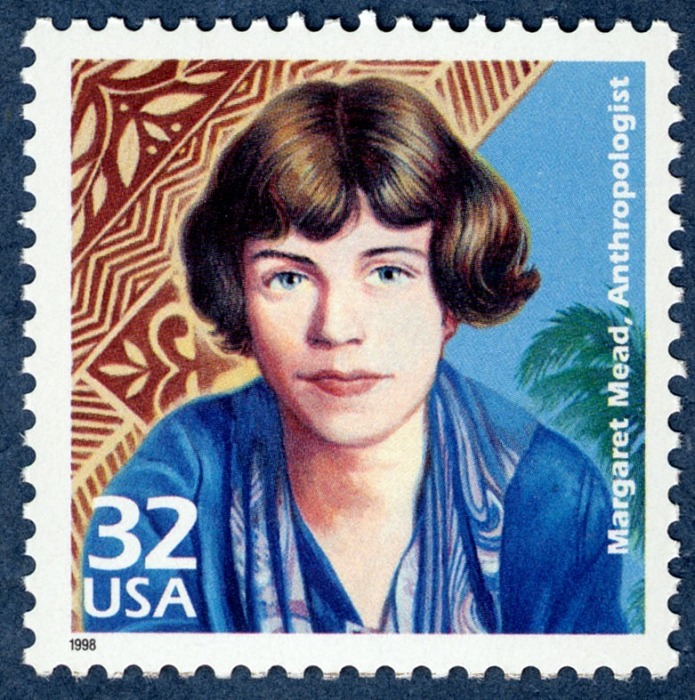

A lot a lot a lot of people were born. Even more than the number of people who died. Eventually history would care about some of them. These included: Louis Armstrong, Walt Disney, Hirohito, Langston Hughes, Margaret Mead, and Ed Sullivan.

As typical, there were far too many military engagements. Such as: the Second Boer War in South Africa (then ongoing); the Philippine-American War (then ongoing); the War of a Thousand Days/Colombian civil war (then ongoing); and the Boxer Uprising/Yihetuan Movement in China (formally ended with the signing of the Boxer Protocol).

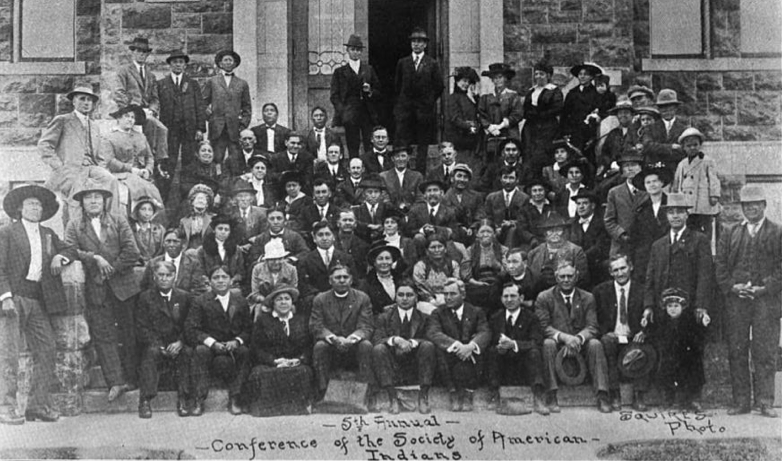

Other political-type stuff happened: The six British colonies of Australia federated to form the Commonwealth of Australia. The US’s Platt Amendment made Cuba a US protectorate. The US and Great Britain signed the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty, giving the US exclusive right to build and manage a canal in Panama. In his first annual message to Congress, US President Theodore Roosevelt stressed the need to treat Native Americans as individuals rather than as members of separate sovereign nations, and to break up tribal funds in the same way allotment broke up tribal lands.

We got some cool new technologies: Guglielmo Marconi sent the first transatlantic radio transmission; it said “S.” The first United Kingdom Fingerprint Bureau was established at Scotland Yard, using Edward Henry’s classification system; it worked way better than phrenology. Hubert Cecil Booth patented a dust removing suction cleaner and started offering mobile cleaning services; his vacuum was large enough to frighten horses (it was also drawn by horses. This sounds messy). Satori Kato introduced his vacuum-dried coffee granules – aka instant coffee – at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, NY. (Also where President McKinley was shot. Yikes.).

There was a bunch of art and culture: Beatrix Potter published the Tale of Peter Rabbit. Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche posthumously published her brother Friedrich’s The Will to Power. H.G. Wells got it close with The First Men in the Moon (would have nailed it with first man on the moon…). Anton Chekhov’s play “Three Sisters” premiered at the Moscow Art Theatre. Vincent Van Gogh had his first retrospective, in a gallery in Paris. Pablo Picasso had his first major exhibit, also in a gallery in Paris. Sergei Rachmaninoff composed Piano Concerto No. 2; Claude Debussy offered Pour le piano; and Edward Elgar started his Pomp and Circumstance series with Marches No. 1 and 2 ( graduation ceremonies had no idea what was coming for them). But Americans REALLY loved parlor ballads, ragtime, and marching band music; they still could not get enough of Sousa’s Band’s Stars and Stripes Forever.

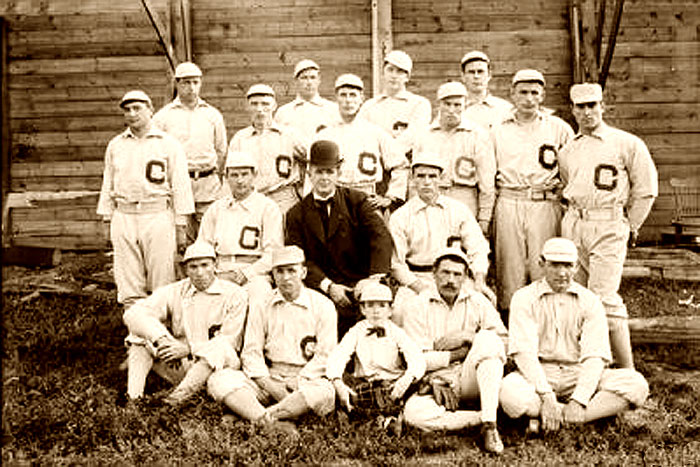

Are sports art and culture? Let’s just call it sports: The Winnipeg Victorias edged out the Montreal Shamrocks to win the Stanley Cup. Fútbol Club Atlético River Plate was founded in Argentina. The American League was established and the Chicago White Stockings (adorable!) won the first AL pennant. The Pittsburg Pirates took the National League pennant.

The first Nobel Prizes were awarded in Stockholm to Wilhelm Röntgen (Physics), Jacobus Henricus van ‘t Hoff (Chemistry), Emil von Behring (Medicine), Sully Prudhomme (Literature), and jointly to Frédéric Passy and Jean Henry Dunant (Peace).

In other odds and ends: J.P. Morgan incorporated U.S. Steel as the first billion-dollar corporation. Mr. Walgreen opened the first Walgreens. The first successful loop-the-loop roller coaster opened on Coney Island (it was called the Loop-the-Loop). Connecticut set the first speed limit law (12 mph in cities; 15 mph on country roads) and forced cars to stop if they were scaring horses. Schoolteacher Annie Edson Taylor celebrated her 63rd birthday by going over Niagara Falls in a barrel and surviving, proving…something?

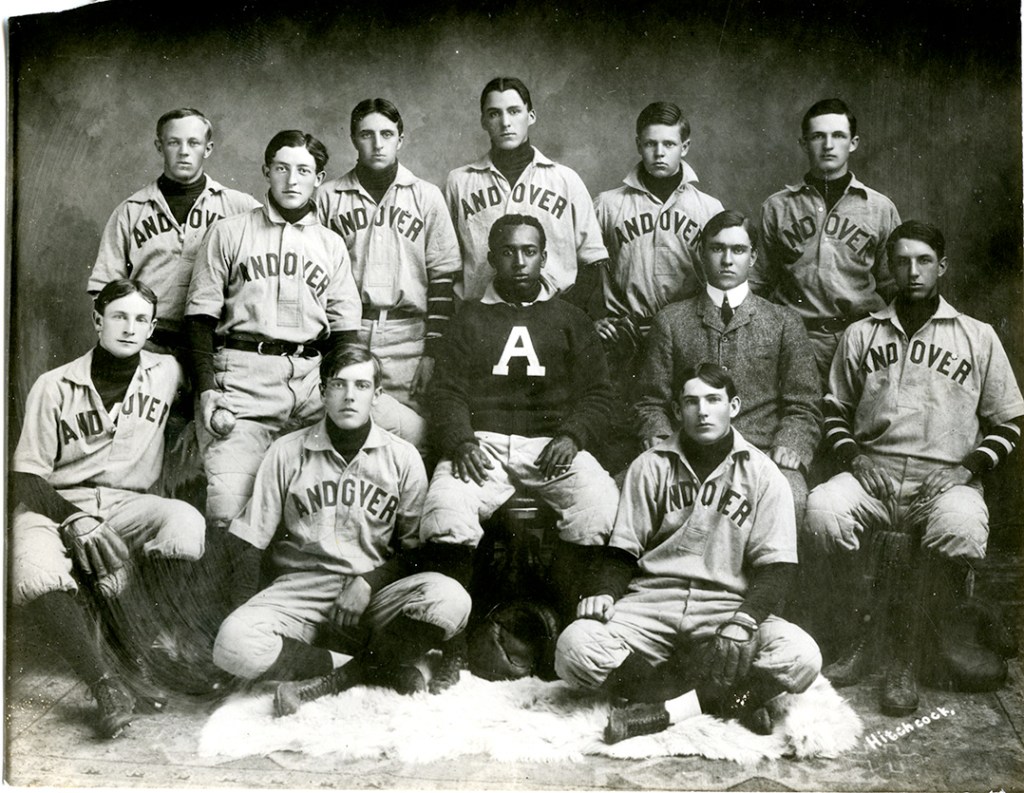

Immediately closer to home: fifteen young women graduated from Abbot Academy, and William Clarence Matthews graduated from Phillips Academy. No one knew it yet, but Matthews would go from leading the batting average on Harvard’s baseball team to playing on the Burlington, Vermont team of the Northern League, making him the only Black player in any white professional baseball league at the time. When he was barred from playing in the Major League he had to settle for being a lawyer instead, eventually getting appointed to the Justice Department by President Calvin Coolidge. Big mistake, MLB. Huge.

Finally, Churchill House was moved a block down Main Street, to make room for construction of the Peabody Institute building. And the rest is history.

[For more on gallery images: Illustrated London News; Margaret Mead stamp; British and Japanese forces engage Boxers in battle; Melbourne Rejoices in the Commonwealth; Booth’s vacuum cleaner at work, 1903; Jagtime Johnson’s Ragtime March; 1901 Chicago White Stockings; Nobel Prize medal; 1901 Kidder Steam Runabout; 1901 Circle]