Contributed by Marla Taylor

Did you know how beautiful New Mexico is? I had the opportunity to travel to the Albuquerque and Santa Fe areas this July and can definitely recommend making the trip.

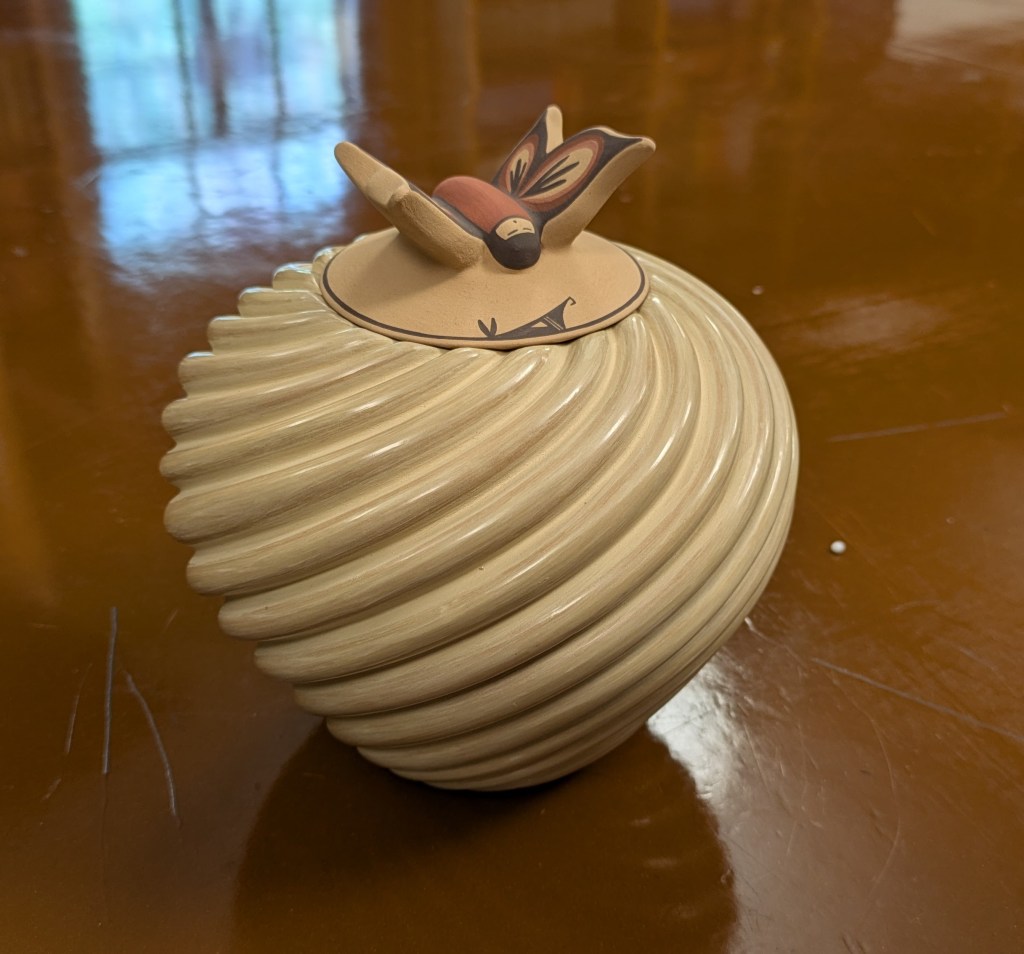

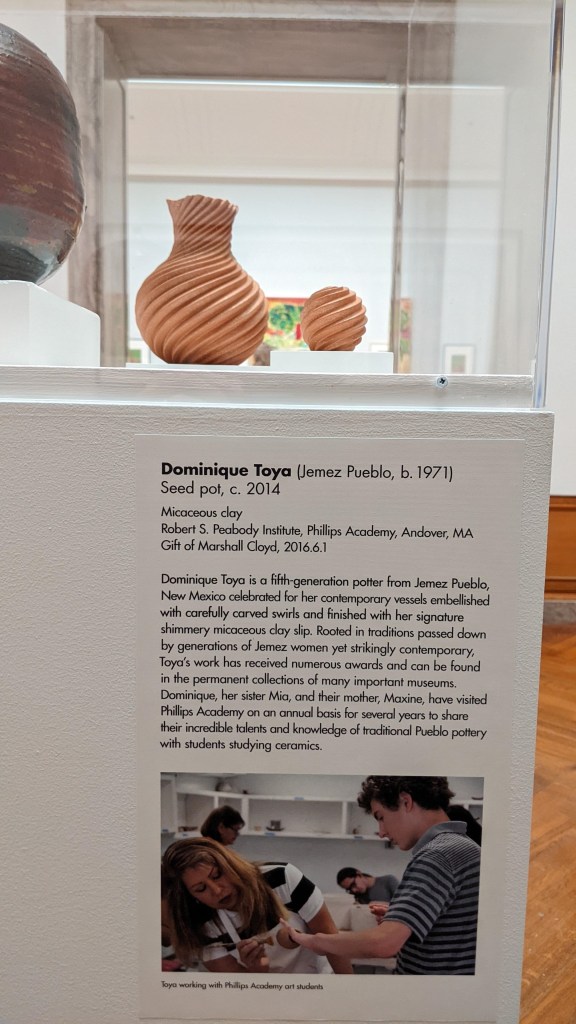

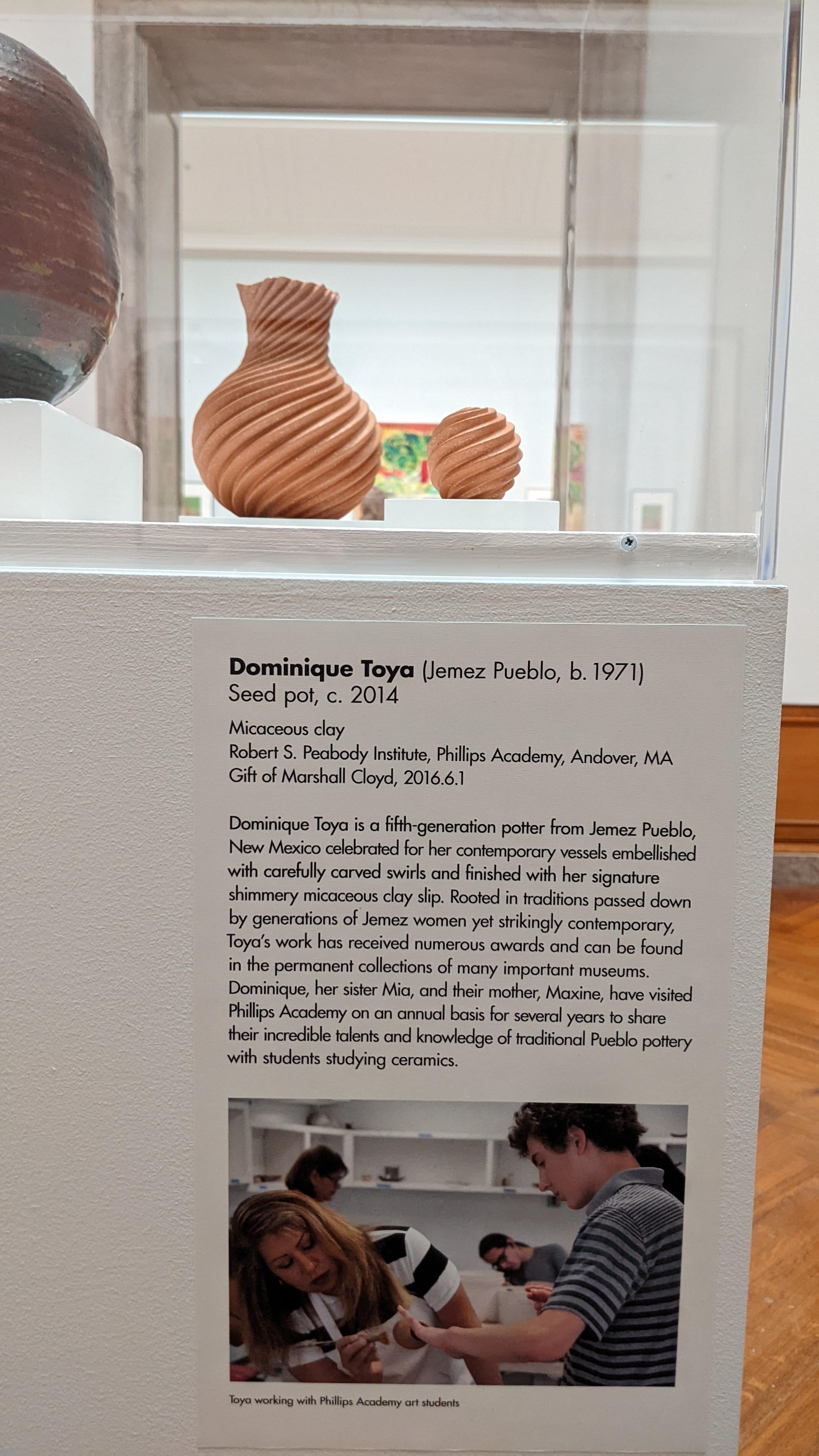

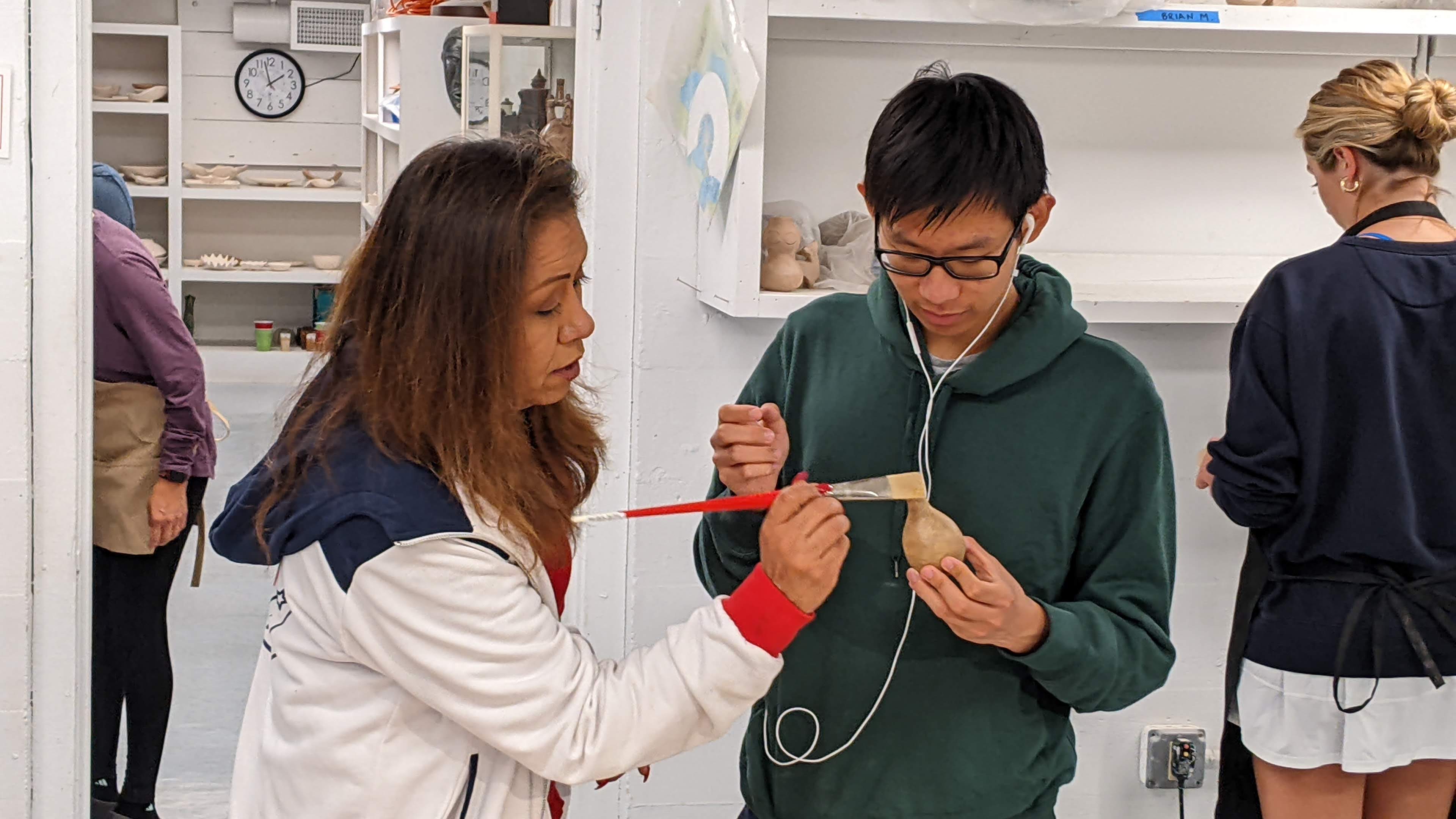

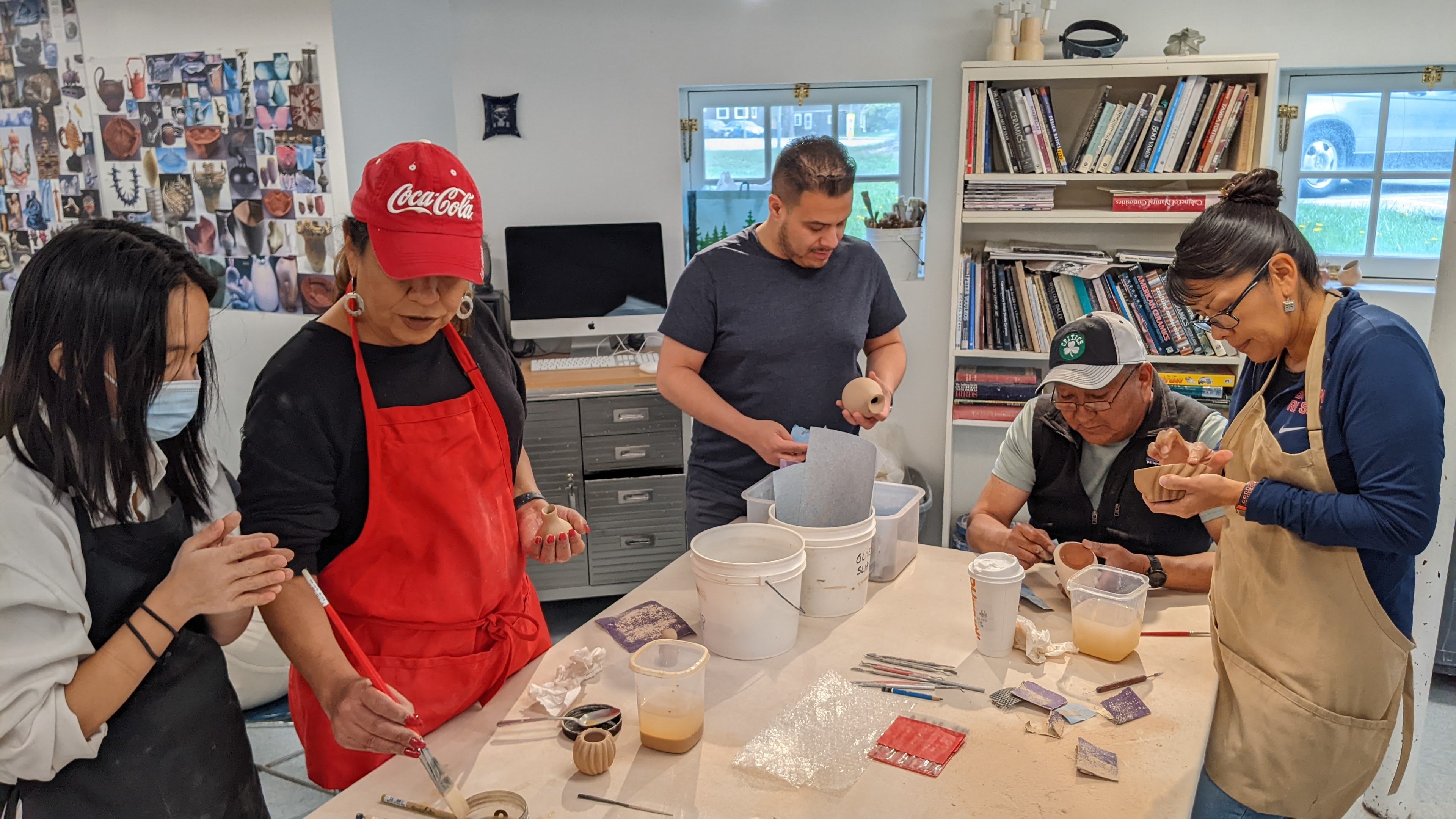

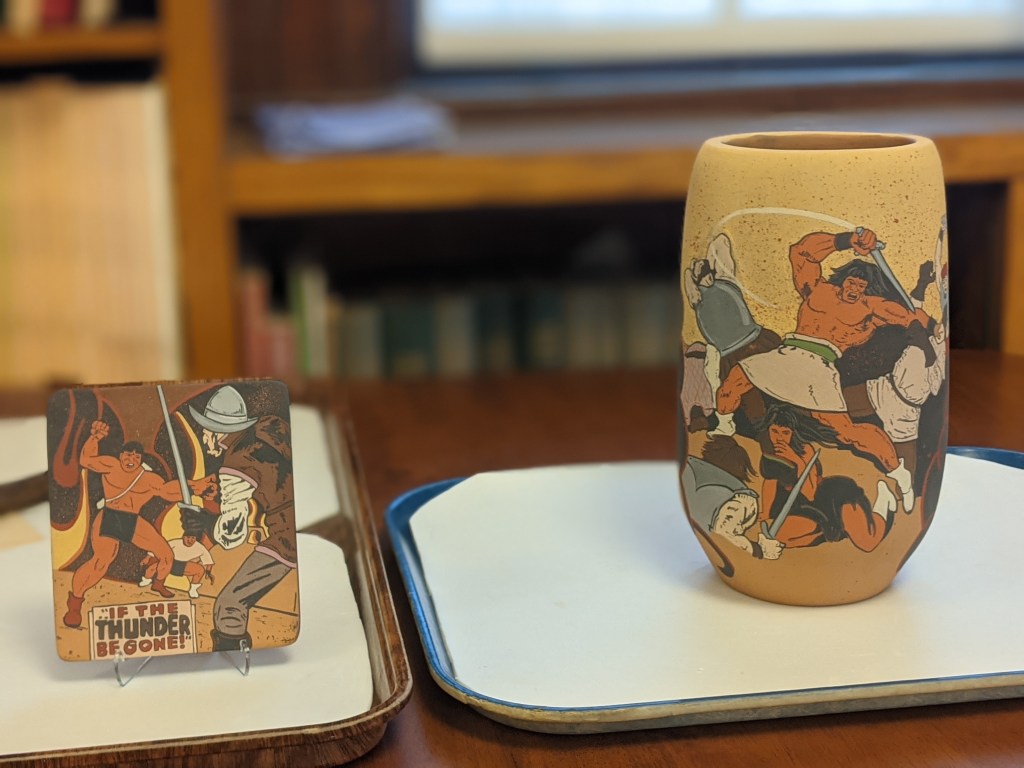

The Peabody Institute actually has a long relationship with New Mexico. In the 1920s, Alfred Kidder excavated Pecos Pueblo on behalf of Phillips Academy (what is now the Peabody Institute). The ripple effects of that work included repatriation work with the Pueblo of Jemez, a long-term loan with the Pecos National Historical Park, inter-institutional collaboration, relationships with Jemez artists, and incredible learning opportunities for the students at Phillips Academy.

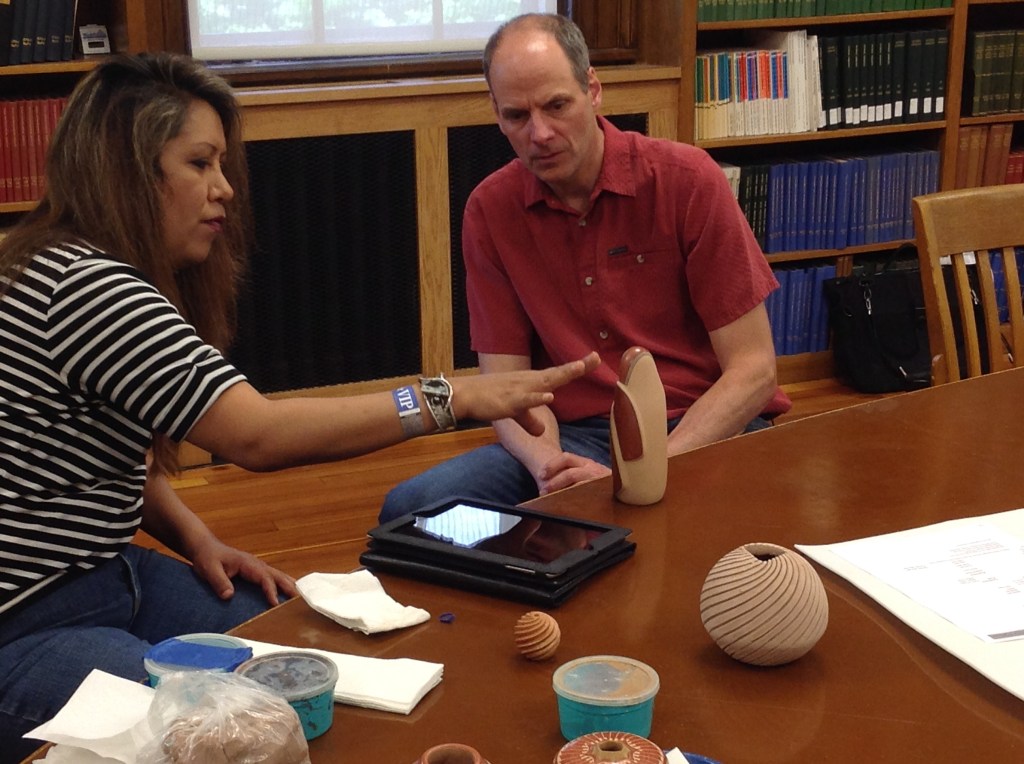

While I had been to the Pueblo of Jemez before this summer, I had not had the opportunity to see the Pecos archaeological site or Pecos National Historical Park before. It was truly a pleasure to experience the site in-person and get an understanding of how Pecos sits in the landscape. I was also able to view their wonderful exhibit, spend time with the Museum Curator to view the collections on loan from the Peabody, and meet several dedicated park staff members. I am grateful for the opportunity to spend that time with them all.

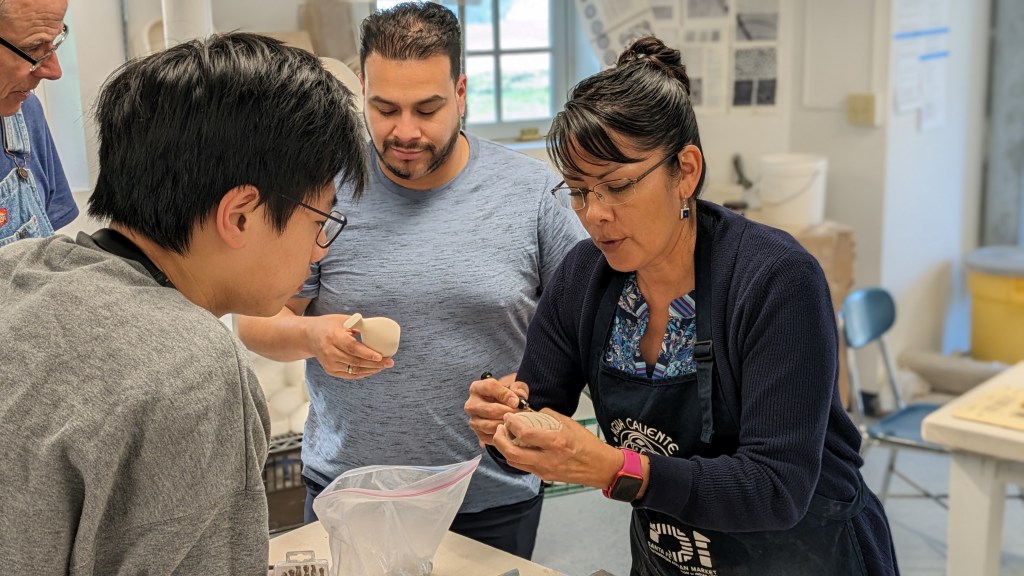

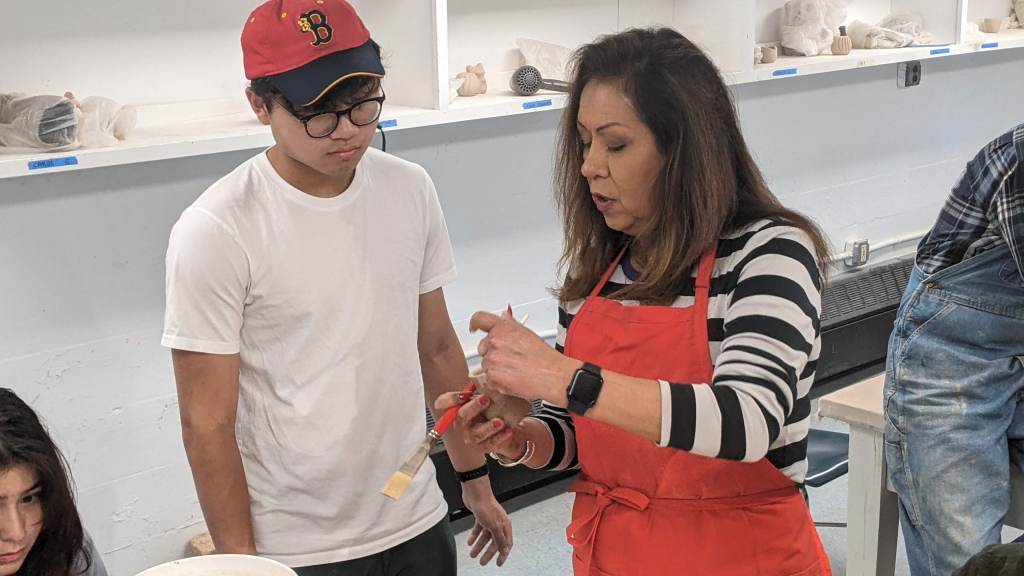

After my time at Pecos, I went to the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe to facilitate the final review session of the Indigenous Collections Care (ICC) Guide. This is a project that I have been working on for awhile and it was excited to be entering the final stages. Although the review session had to be rescheduled due to complications with our IMLS grant, we had a wonderful group of people to discuss the ICC Guide and help us move forward into the final stages of development.

The ICC Guide provides a framework to respect and recenter collections stewardship practices around the needs and knowledge of Indigenous community members. The Guide speaks to individuals engaged in collections stewardship within museums and collecting institutions. It is aimed specifically at museum professionals, emerging and established, and individuals who are seeking clarification, support, and validation to pursue culturally appropriate care.

Next steps are to send the Guide out for copy-editing and graphic design. A final version will be ready to be shared in the summer of 2026.

My time in New Mexico was amazing and I hope you can visit there sometime soon!