Contributed by Ryan Wheeler

The Peabody Institute has a history with New Mexico stretching back to 1915 and the beginning of Alfred Kidder’s nearly fifteen yearlong excavation at Pecos Pueblo outside of Santa Fe. In May, I had an opportunity to visit New Mexico, with stops at the Pueblo of Jemez and Pecos National Historical Park. The connections between Jemez and Pecos are even older, with a merger of the two communities in 1838, as the population at Pecos dwindled, and Jemez remained as the only place where Indigenous language Towa is spoken.

My first stop was the Pueblo of Jemez, where I had an opportunity to visit with tribal archaeologist Chris Toya, and tour the Jemez visitor center, which exhibits around 100 of the objects that Kidder removed from Pecos. Jemez, also called Walatowa, meaning “this is the place,” is situated in some amazing scenery of the Canon don Diego. The canyon is well known as “red rocks,” a reference to the vibrant red and orange hue of the sedimentary rock walls, capped by a volcanic tuff. When I was there, it had just rained, making the canyon wall even brighter. Jemez is typically closed to outsiders, but the Walatowa Visitor Center is open to all and has some great exhibits on Jemez history and culture. I spent the night at the Laughing Lizard in nearby Jemez Springs, where I had stayed with my family last summer.

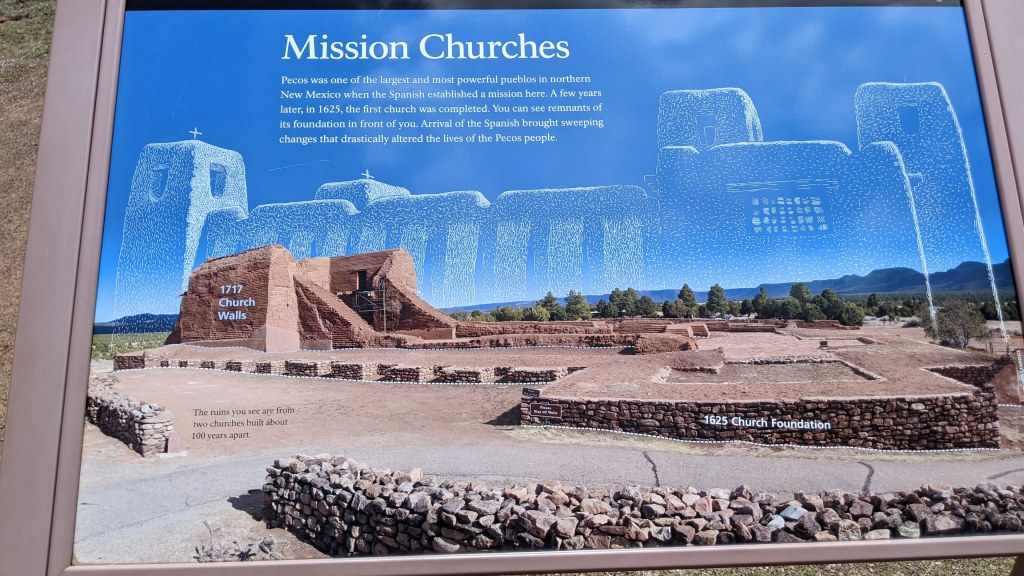

I got up early the next morning and drove to Pecos National Historical Park. The visitor center there has just received a significant update and includes more of the objects removed from Pecos by Kidder. Audio narration of the exhibits was in English and Towa, so great! The ruins of a Spanish church dominate the top of the plateau here and wandering the trails takes you past the remains of Pecos Pueblo. Ongoing preservation work at the church included capping the walls with contemporary adobe to protect the ancient features. I also had an opportunity to see the storage facilities where Pecos objects are housed and talk with Rhonda Brewer, park museum curator, and Jeremy Moss, cultural resource coordinator.

My final stop was in Albuquerque, and from there I ventured out to Chaco Canyon National Historical Park. I’ve been wanting to visit Chaco for some time, but it’s pretty much an all day excursion. I signed up for a tour by Kialo Winters of Navajo Tours USA. I was a little nervous about the drive to Chaco. After turning off US 550, the 20 miles or so to the Chaco visitor center go from paved to dirt to pretty bumpy. Apparently its bad when its wet. I have a terrible sense of direction, so was mostly worried about getting lost, but the road is well marked and was fine when I drove it.

Kialo shared that really to see everything at Chaco you would need about three days, but his tour hit the high notes, including the expansive ruins of Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito. I highly recommend the Navajo Tours USA tour—Kialo is incredibly knowledgeable and up to date on Chacoan archaeology and history, and he drew heavily on Navajo and Zia Pueblo Indigenous knowledge. It was impressive to walk through the ruins of what were once four-story high buildings at Pueblo Bonito and find the places where the different styles of masonry connected and extended the buildings. Occupation here dates from 850 to 1,250 CE. The Peabody also holds a number of objects from Pueblo Bonito related to Warren Moorehead’s 1897 visit to the site. As Teofilo, the author of Gambler’s House blog notes, Moorehead ransacked rooms 53 and 56, near other rooms that had produced fabulous finds, like cylinder jars and macaw burials. In fact, Moorehead removed several complete and fragmentary cylinder jars from the site.

Overall, it was a productive few days in New Mexico. It was great to visit Chaco Canyon, one of the most impressive cultural sites in the United States, as well as visit with folx at Jemez and Pecos. As many of you know, the Peabody Institute sponsored the long-running Pecos Pathways student travel program, and there has been a lot of interest in creating a new version of that trip. I’m not sure if or when that might happen, but we will work on further contacts, assess interest on campus, and see what happens. Certainly all of the above would be important stops!