Contributed by Ryan J. Wheeler

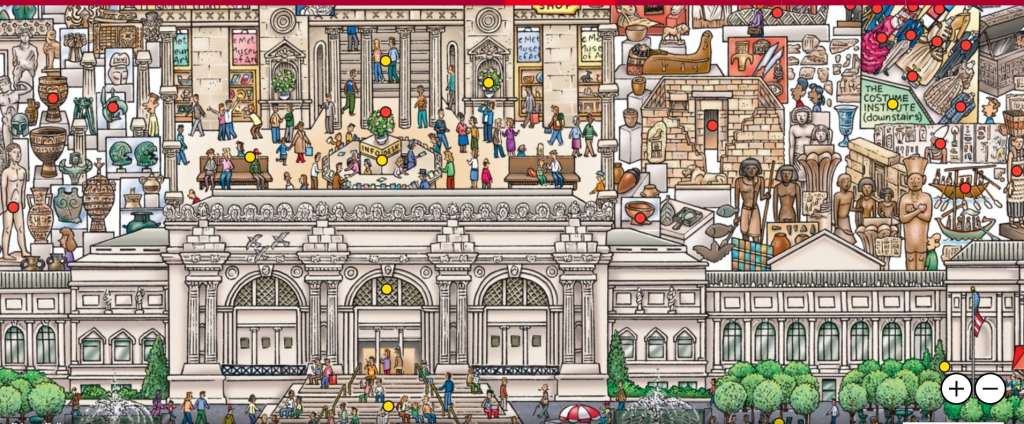

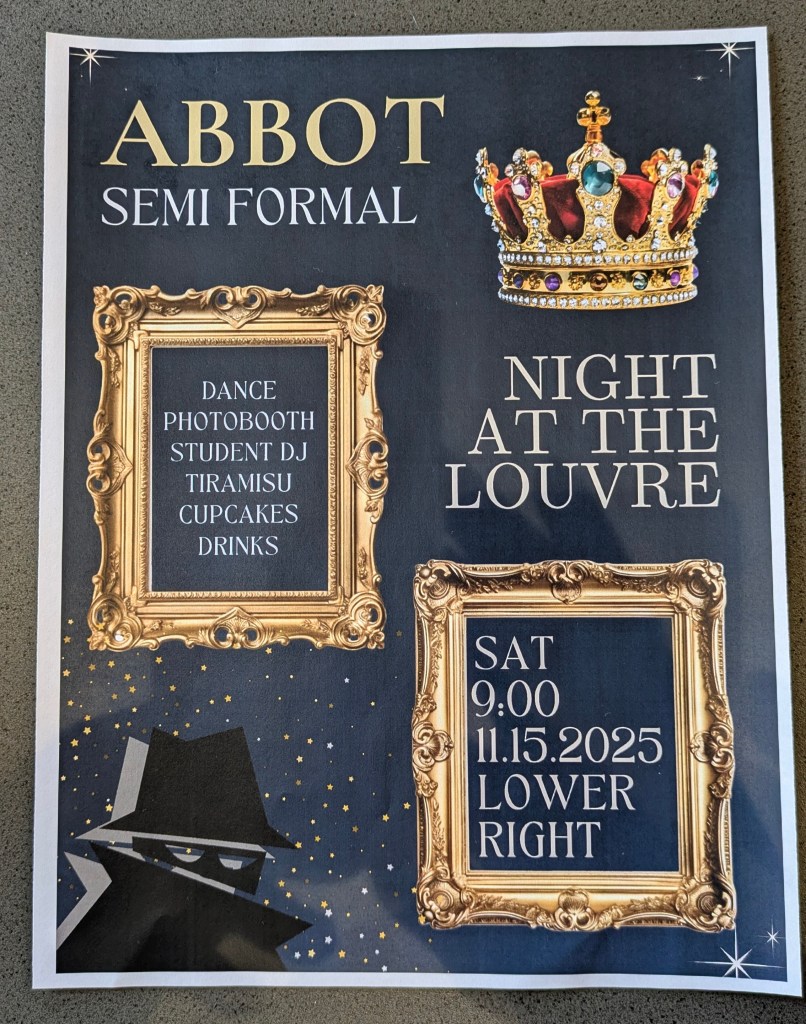

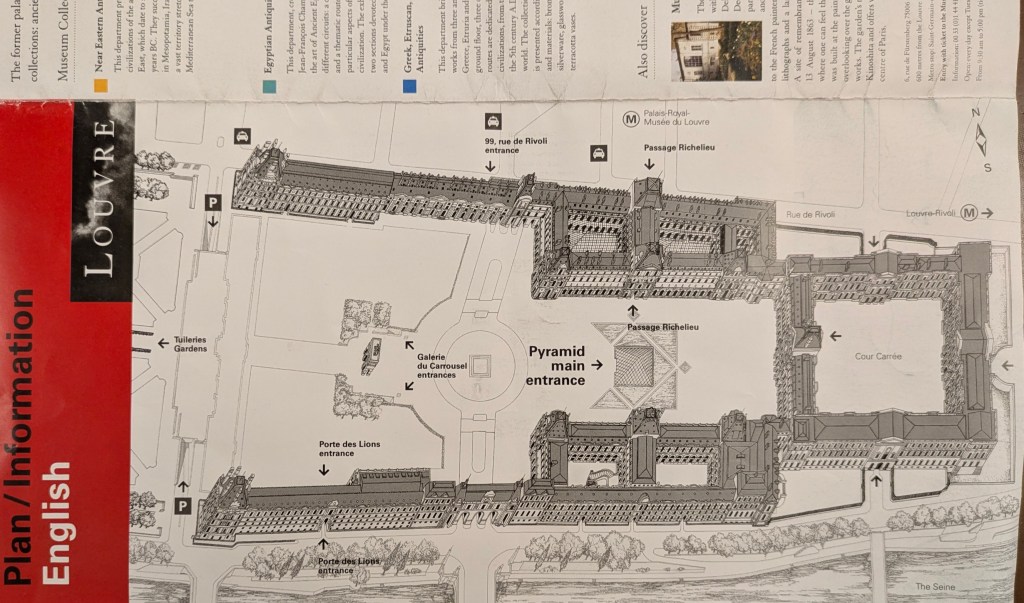

The brazen theft of crown jewels from the Louvre on October 19, 2025 fed the ongoing public fascination with museum heists. From details like which mobile work platform was used to access the museum to issues with security, there was almost endless interest and speculation. Even the dapper high school student mistaken for a French detective captured the world’s attention. Not surprisingly, the museum heist is a classic movie and tv trope from the recent The Mastermind (2025) to How to Steal a Million (1966) to the multiple versions of The Thomas Crown Affair (1968, 1999—and apparently a new one in production!), and many others. Fictional literature about heists could occupy a library. Even students here at Phillips Academy hosted a Louvre heist-themed dance! The exciting and glittery portrayals of museum heists, however, often veer far from the real blend of cunning, avarice, ineptitude, and the real mess that museum thefts leave in their wake. Just a few days before the Louvre heist, thieves gained access to the Oakland Museum’s storage spaces, taking over 1,000 objects, including many Native American items.

When I joined the Peabody Institute in 2012, former director Jim Bradley told me to be on alert for missing items, presumed stolen at some unknown point in the museum’s past. Early in Jim’s tenure as director, he had been involved in the recovery of a shell gorget from the Etowah site in Georgia. Since that time several collectors have returned items from Etowah and Maine, and others have been tracked down with the aid of the FBI art crimes team. What we now understand is that the Peabody Institute experienced two thefts—one in late 1970 or early 1971, and another in 1986.

Marla Taylor and John Bergman-McCool recount the theft by George McLaughlin in 1986 in their 2020 blog post. McLaughlin gained access to the Peabody’s collection housing areas at a time when the institution lacked professional staff. That made it easier, but he also stole from other museums across New England and several private collectors. He was ultimately caught by the FBI and prosecuted, but not before removing most of the catalog numbers from the thousands of stone tools that he had taken. It was unclear what McLaughlin’s plans were, but it seems he was readying items for sale. And while the FBI arrest prevented that, to this day we have a large number of items that have lost their original provenience—in other words, a big mess.

I’ve shared before about an earlier theft at the Peabody Institute (also, see my article in the April 2018 SEAC newsletter). Based on correspondence, we are confident that items from Georgia and Maine were stolen in late 1970 or early 1971 while exhibits were being refreshed and updated. These items had been on display when they were photographed to illustrate Dean Snow’s 1976 book The Archaeology of North America. It seems like they were taken while awaiting reinstallation in the exhibits. As I mentioned above, a number of these items have been returned, either by conscientious collectors or through an investigation by the FBI art crimes team, begun in January 2018 when one of the Etowah items was returned to us. Many of these items are funerary objects and subject to repatriation under the Native American Graves Protection & Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Their continued absence complicates those repatriation efforts.

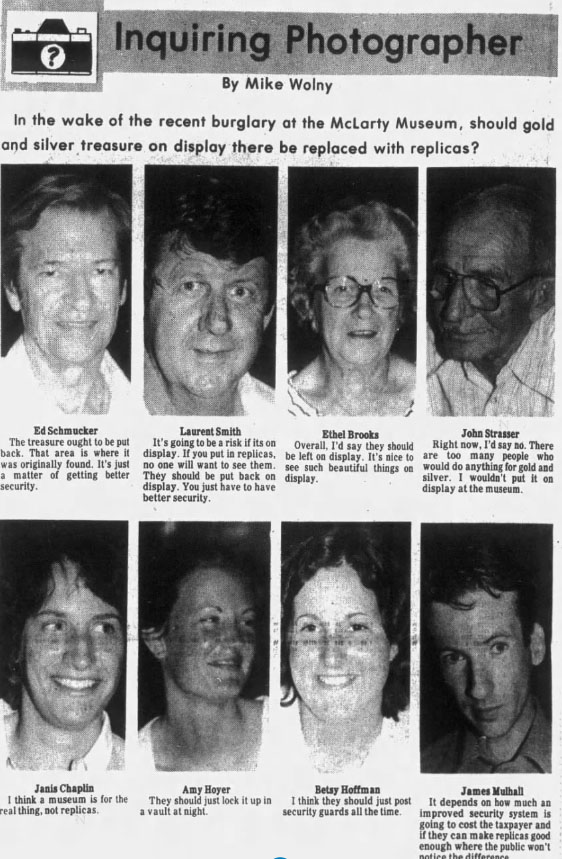

Unlike the glamourous (or humorous) fictional depictions of museum heists, these are often crimes of opportunity, driven by greed or misguided ideas about the role of museums in caring for and sharing art and culture. I think one example from my past career as Florida’s state archaeologist aptly captures the stupidity of the museum heist. Our collections in Florida included impressive holdings recovered from the shipwrecks of Spanish treasure galleons. Loans to the McLarty Museum near the survivor’s camp of the 1715 fleet wreck included gold coins and gold bars. In 1980, thieves defeated locks and security systems, but when confronted with the reality of disposing of a gold bar, things took a weird turn. They used a hack saw to begin cutting a gold bar into more saleable (or tradeable) pieces before being apprehended. The gold bar was recovered, but the saw cut end remains at large. During our annual 100% inventory of precious metals and coins our outside auditor frequently questioned what was going on with the clearly chopped up gold, so much so that we finally tucked some of the paperwork and news coverage with the piece to allay fears that we were helping ourselves. The thief in that case ultimately criticized press coverage, telling the court that he was “by no means a professional burglar” and that the theft was just a “reckless impulse.” So, enjoy that museum heist movie or book, but remember, it’s a far cry from the real mess made by these thefts.