Contributed by John Bergman-McCool

Last May the Robert S. Peabody Institute hosted visiting researcher, Dr. Kurt Rademaker. Dr. Rademaker is an Associate Professor and Director of the Center for the Study of the First Americans Laboratory at Texas A&M University. His research interests include early human ecology and settlement dynamics of the central Andean highlands.

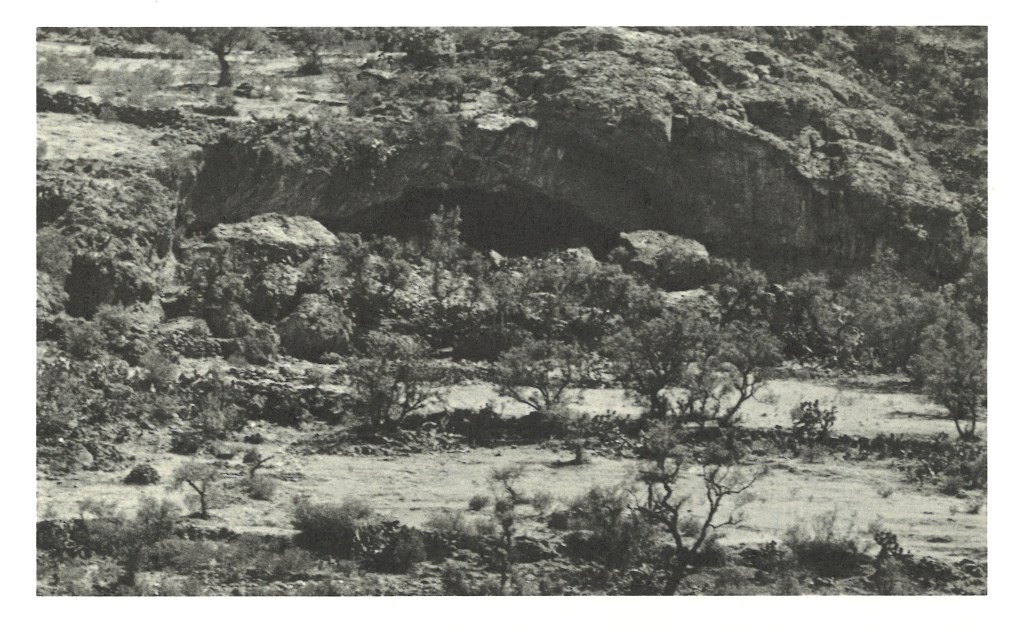

Dr. Rademaker came to the Peabody to view materials collected by Richard “Scotty” MacNeish from the Ayacucho Valley in the Andean highlands. Between 1969 and 1972, MacNeish led an interdisciplinary team that searched for evidence of the origins of agriculture and civilization in South America.

Based on previous work conducted on the Peruvian coast, MacNeish and others hypothesized that agriculture originated in Peru’s Andean highlands. The Ayacucho Valley encapsulates diverse habitats spanning a range of elevations. It also contains dry caves with long stratigraphic sequences, two criteria MacNeish utilized in his study of the origins of agriculture in the Mexico’s Tehuacán Valley.

Botanical remains discarded by humans, including domesticated plants, can be well-preserved in dry caves, while long stratigraphic sequences give archaeologists the ability to see how things change over long spans of time. MacNeish was looking for evidence of human cultural development, including domesticated plants across time and habitats.

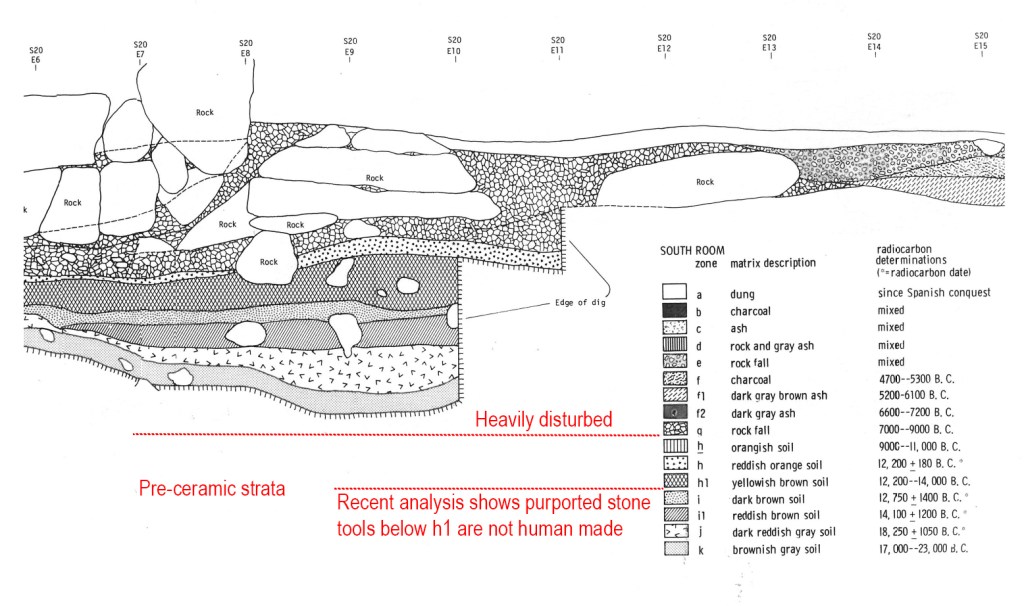

Interestingly, and unrelated to the question of plant domestication, MacNeish’s summary of excavations at one site, Pikimachay, concluded that humans and now-extinct Pleistocence animals may have interacted. This was based on the presence of artifacts and extinct animal remains in the same pre-ceramic stratigraphic layer. The claim was supported by radiocarbon dating which returned dates of roughly 14,000 and 23,000 years before present. However, this conclusion has always been somewhat controversial since the dating methods do not meet scientific standards of quality control, not to mention they contradicted widely held notions of the peopling of the Americas.

Radiocarbon dating, at the time, required a large amount of sample material. MacNeish gathered material from several sources spanning a wide area. In the intervening years, isotope analysis has improved to the point where only one gram of sample material is needed. Now a single bone with clear stratigraphic origin can be sampled.

Additionally, sample preparation can now isolate carbon from the item being dated and remove carbon from the surrounding sediment. Previous methods couldn’t parse these sources and may have resulted in dating the burial environment. This can help determine if the sample was moved from it’s original stratigraphy by burrowing animals or other natural forces.

The story of when people arrived in the Americas has changed over time as new discoveries led archaeologists to question existing hypotheses. At the time of MacNeish’s Ayacucho project, the commonly held belief was that the first people arrived at the end of the Ice Age, by way of the Beringia land bridge and ice-free corridors. The earliest evidence of human presence was at Clovis, New Mexico, dated 13,250 to 12,800 years before present. His discovery meant that people may have arrived in North America much earlier if they were established in Peru 14,000 to 23,000 years ago.

Revisiting MacNeish’s Ayacucho materials offers an intriguing opportunity to confirm his findings. Recent work has revealed that the stone tools found in the lowest strata (see figure 3) were naturally occurring and not made by people, perhaps ruling out the oldest dates MacNeish obtained. However, the researchers confirmed that human-made tools and cut animal bones are present in earlier layers (strata h, h and h1).

Dr. Rademaker has proposed sampling as many animal bones as possible from pre-ceramic stratigraphic layers. If any remains are from the Pleistocene Epoch, then MacNeish’s results will be supported and will add further support to a pre-clovis peopling of the Americas. If the remains are younger, from the Holocene Epoch, then it is likely that they were deposited in lower strata through some manner of disturbance.

During Dr. Rademaker’s visit he spent several days reviewing archival materials including field notes, radiocarbon sample data and correspondence. The final day of the visit, Dr. Rademaker collected a sub-set of samples; roughly 1/3 of the total proposed. The bones they were taken from are quite old and may not contain the collagen necessary for isotope analysis. If these samples prove to have viable collagen and they return good dates, Dr. Rademaker will return to collect the remaining samples.