Submitted by John Bergman-McCool

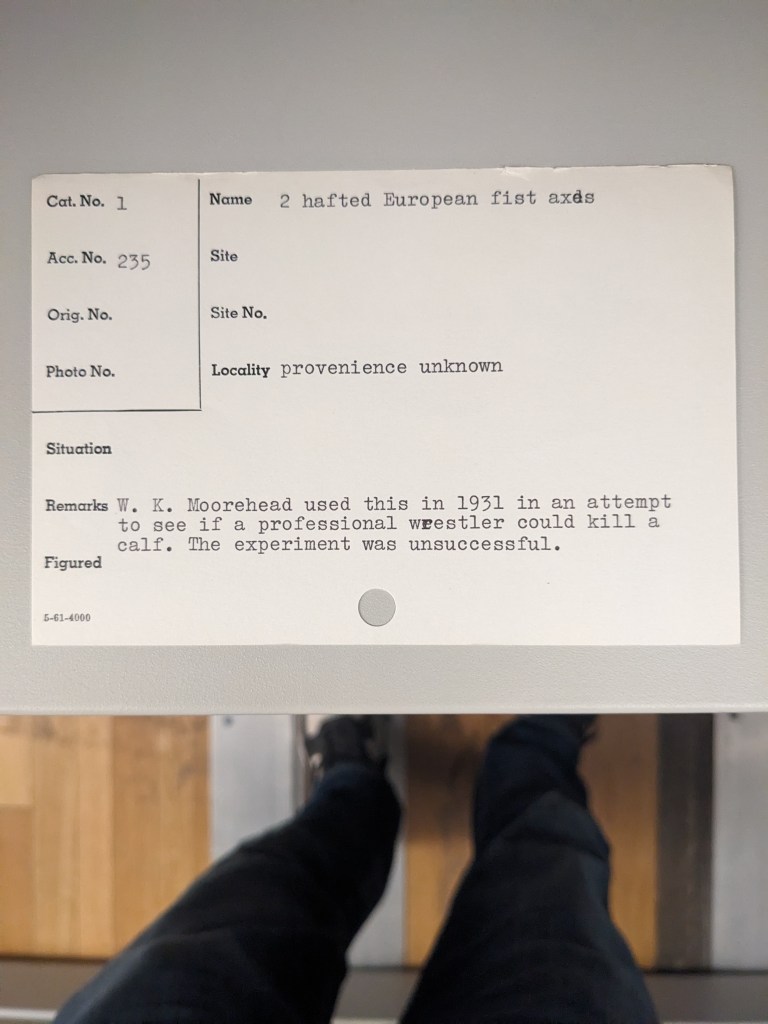

A few years ago, I came across a catalog card with an interesting account in the remarks section. The card read “W. K. Moorehead used this in 1931 in an attempt to see if a professional wrestler could kill a calf. The experiment was unsuccessful.” There is a lot to unpack from this card. It references experimental archaeology, professional wrestling, and, judged by today’s standards, ethically questionable behavior. I figured that there had to be a story to unearth, but with more pressing work to do, I filed this note away for another time.

The catalog card describes two hafted European ‘fist axes’ (or handaxes). The provenience of the items is unknown. The Peabody acquired a collection of similar European tools shortly before these items were cataloged. It’s possible that the hafted handaxes are somehow related.

Over the past few years this card occasionally comes to mind, or I will see the handaxes. When they do, I will do a quick search of the internet for any related newspaper articles, journals, or archival clues. I’ve looked through our institutional records but haven’t found anything that appears to be related.

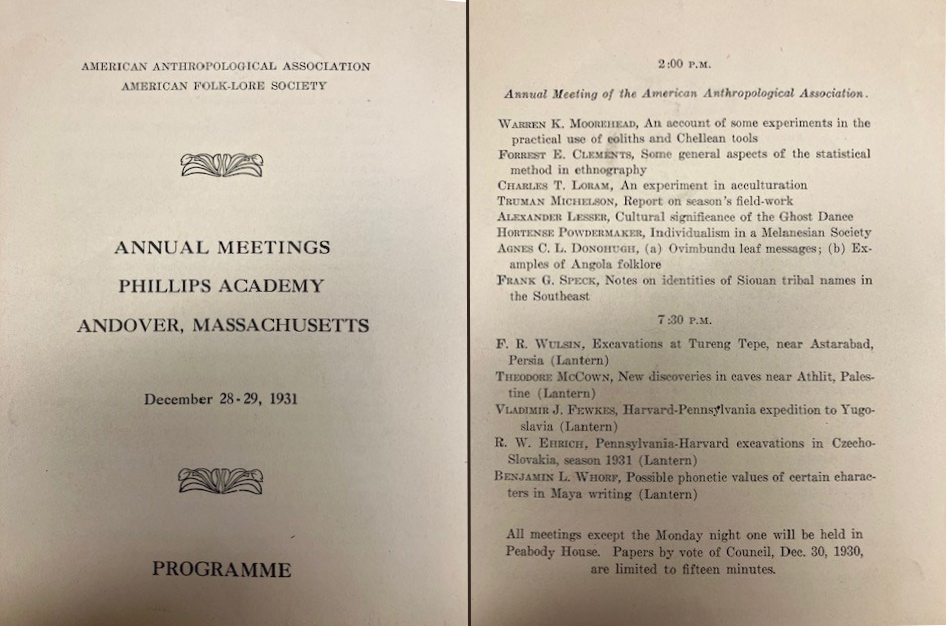

A breakthrough came when I found the minutes from the combined 1931 Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association (AAA) and American Folk-Lore Society. The meeting was held at Peabody House at Phillips Academy on December 28-29. The minutes included a description of a talk given by Warren K. Moorehead titled “An account of some experiments in the practical use of eoliths and Chellean tools.”

The Chellean tools Moorehead references belong to what is today known as the Acheulean stone tool industry. They are named after a site in Saint-Acheul, France where their classification as a prehistoric tool was first broadly accepted. Acheulean handaxes are distinct and have come to define Acheulean stone tool technology overall. The hafted hand axes in question are unquestionably Acheulean in form, with the hafting being a recent addition.

The distribution of these tools is wide-ranging geographically and temporally. The oldest examples date to 1.76 million years ago. An end date for their use has been placed between 300,000 and 100,000 years BP. Some handaxes are very large, measuring 2 feet, while others are quite small, just 6 inches.

They have been found in Africa, Europe and west, south and east Asia. They are very old examples of stone tool technology and would have been made by hominids, such as Homo erectus.

-A quick note about eoliths. These were once thought to be stone tools and were subject to heated debate for many decades. They have been found in deposits that vastly predate the Acheulean. They are now recognized as naturally occurring geofacts and are not of human origin.

Finding the meeting minutes describing Moorehead’s presentation seemed to be one step closer to an account of the experiment-gone-wrong mentioned in the catalog card. Armed with more information and a date to work with, I did another round of searching on the internet and within our archives.

Eventually, I contacted the Ohio History Connection (OHC). Moorehead was the first curator at the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society (OAHS) before coming to Phillips Academy. After his death in 1939, Moorehead’s family gave many of his papers to OAHS. Our two institutions share some of the same correspondences and we have reached out to them in the past.

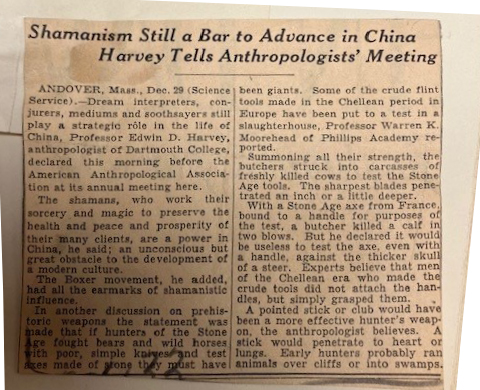

Amazingly, OHC responded with a newspaper clipping from the New York Times that provided more context about the talk Moorhead gave at the 1931 AAA meeting. The article mentions that the tools were used by butchers in a slaughterhouse on carcasses and one living animal. The butchers declared the tools to be ineffectual, and Moorehead proposed that sticks or clubs would have been better suited as hunting tools.

Today, experimentation of this nature on live animals would be ethically inconceivable. Scientific research is meant to manipulate variables in controlled situations to study factors relevant to the proposed question. Moorehead’s experiment didn’t take into account the many varied sizes of handaxes and whether they should be hafted or simply held in hand. Testing a range of sizes and handling methods might lead to better results. However, this and any future replication or refinement of Moorhead’s conditions would certainly lead to increasing levels of harm to animals.

A researcher who has engaged in experimental archaeology shared via correspondence some of the alternatives and ethical considerations of modern experimentation in the field. Colleagues testing projectile point penetration utilized targets made from meat and meat substitutes, such as ballistic gel and clay. The meat used for the targets needed to be ethically sourced (from a hunter or butcher for example) and would otherwise have been discarded if it not used in the experiment.

Sometimes substitutions for animal remains are unavoidable. An article on the topic of animal resources in experimental archaeology outlines concerns of sample procurement. Scientific studies often require large sample sizes. Animal remains are non-renewable resources that have limited availability. These samples are linked to the death of animals, no matter how they are procured. In these situations, modern researchers must strike a balance between scientific rigor and ethical integrity.

Returning to the catalog card and newspaper article concerning this experiment; it is interesting to note that the professional wrestler in one, is a slaughterhouse butcher in the other. I was hoping any notes Moorehead used to prepare his presentation or other related correspondence could provide more information, but I have yet to find them.

Both the card and article declare the experiment to be a failure, seemingly as tools for hunting and maybe butchery. To be sure, the hafting has left very little of the cutting edge of one of these tools available for penetration.

Subsequent experiments with Acheulean handaxes have found them to be effective tools for a wide range of tasks aside from hunting including butchering animals, stripping wood, processing plants and digging. These experiments are supported by surface wear pattern studies. It is unclear whether these tools were ever used for hunting, which Moorehead’s sensational experiment somewhat confirms.

Websites with more information on Acheulean culture:

Journal article outlining challanges associated with animal experiments in archaeology: