Contributed by John Bergman-McCool

This blog represents the thirteenth entry in a blog series – Peabody 25 – that will delve into the history of the Peabody Institute through objects in our collection.

If you travel on state routes through the Northeast this time of year, you will likely witness a continuous stream of hand-painted signs advertising sweet corn. On a recent road trip through Maine, the oft-repeating signs got me thinking about all the places I’ve seen corn cultivated: Washington State, Arizona, the Midwest cornbelt and New England. A quick search on the internet reveals that modern corn varieties can be grown in USDA hardiness zones 3-11 (that’s just about everywhere!). Currently corn is an important crop for many economies across the globe (map of world corn production).

With corn seemingly grown nearly everywhere, you may wonder when and where did it first originate? This question has been the subject of debate among scientists for more than a century. Richard “Scotty” MacNeish, former director of the Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology and influential twentieth century archaeologist, played an important role in untangling maize’s history of domestication.

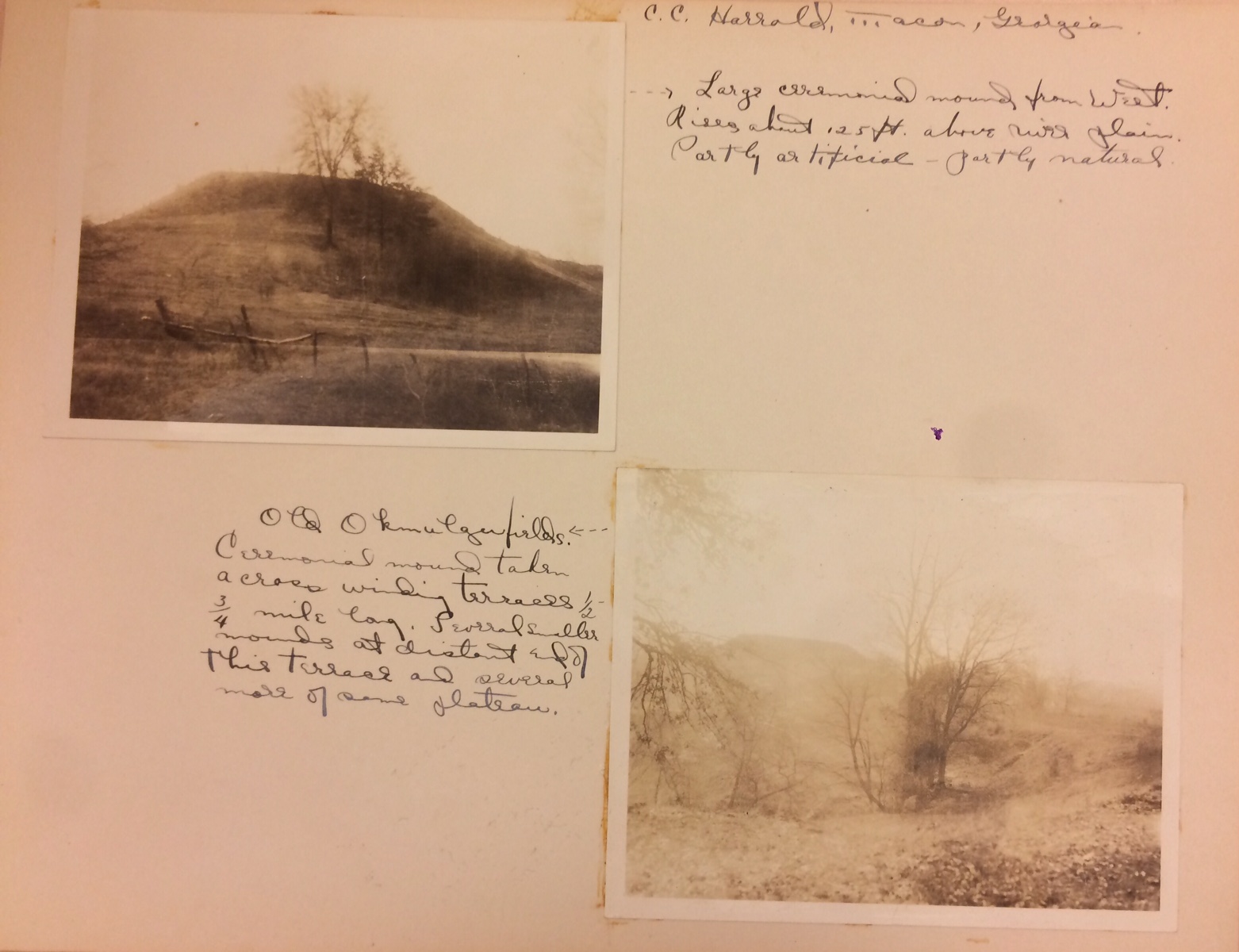

While a doctoral candidate in 1945, MacNeish was sent to Texas and northern Mexico to look for evidence supporting the theory that Mesoamerican migration into North America led to the development of mound building cultures. MacNeish found no link, but he did locate a series ruins, campsites, and dry caves that had the potential for long sequences of human occupation in Tamaulipas, a state in northern Mexico.

In 1948, MacNeish returned for a field season that included the excavation of three cave sites in the Sierra de Tamaulipas. The caves housed a surprising amount of very well preserved botanical remains. During the closing moment of the excavation in Tamaulipas, the crew had all but closed up shop and shipped off their specimens and equipment when three small maize (corn) cobs were recovered from La Perra cave. The excavations in Tamaulipas pushed the age of maize cultivation back to 2,500 BC. The discovery of what was then the earliest evidence of domestication in the Americas would shape the direction of MacNeish’s archaeological research.

A little over a decade later, spurred by colleagues in botany, MacNeish would search farther south for earlier evidence of maize cultivation. In 1961, after years of survey in Central America and southern Mexico, MacNeish found promising dry caves in the Tehuacán valley of Mexico. There he led a multidisciplinary team in the excavation of six cave sites. Among the many discoveries were maize remains recovered from layers dating to 4,700 BC. Tehuacán was theorized as the ancient seat of maize domestication.

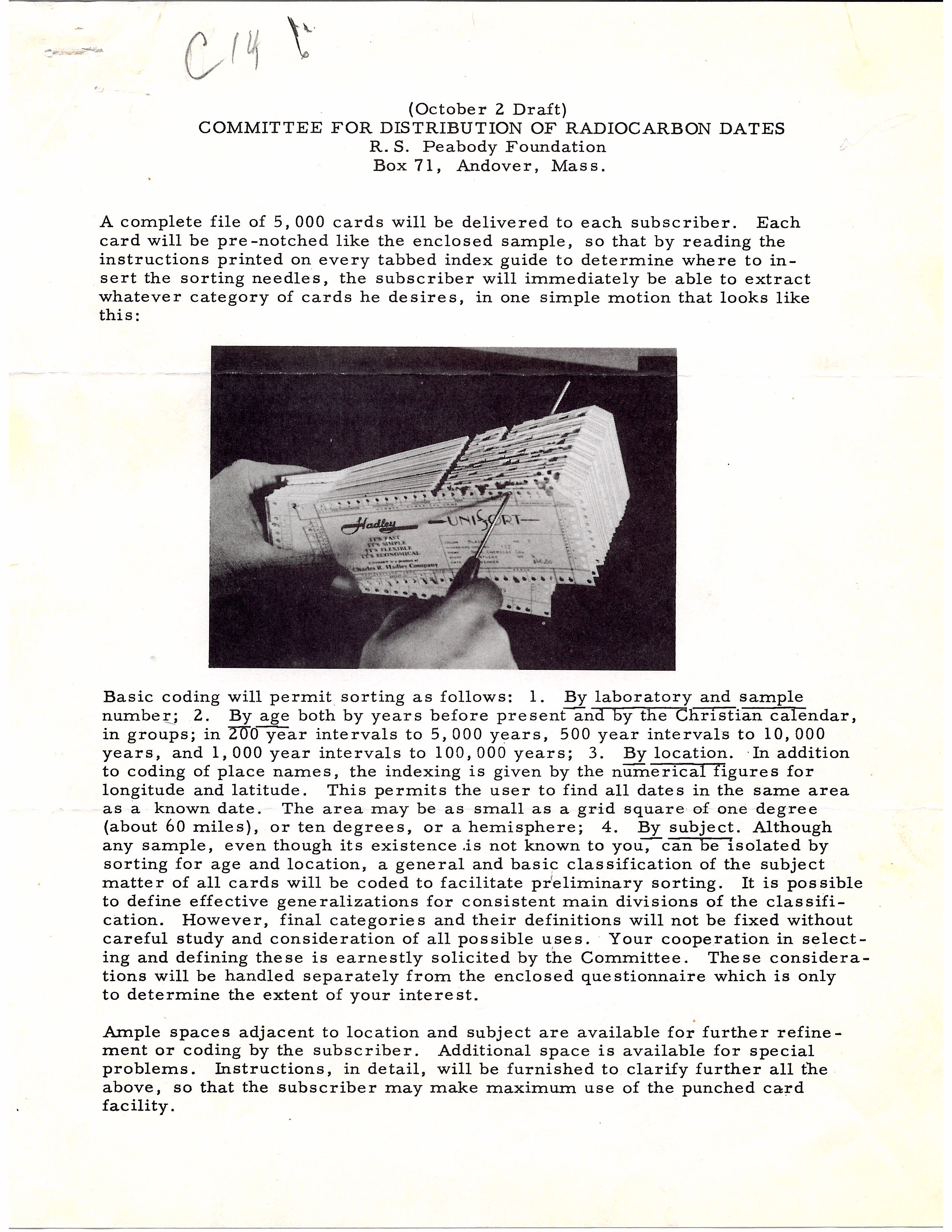

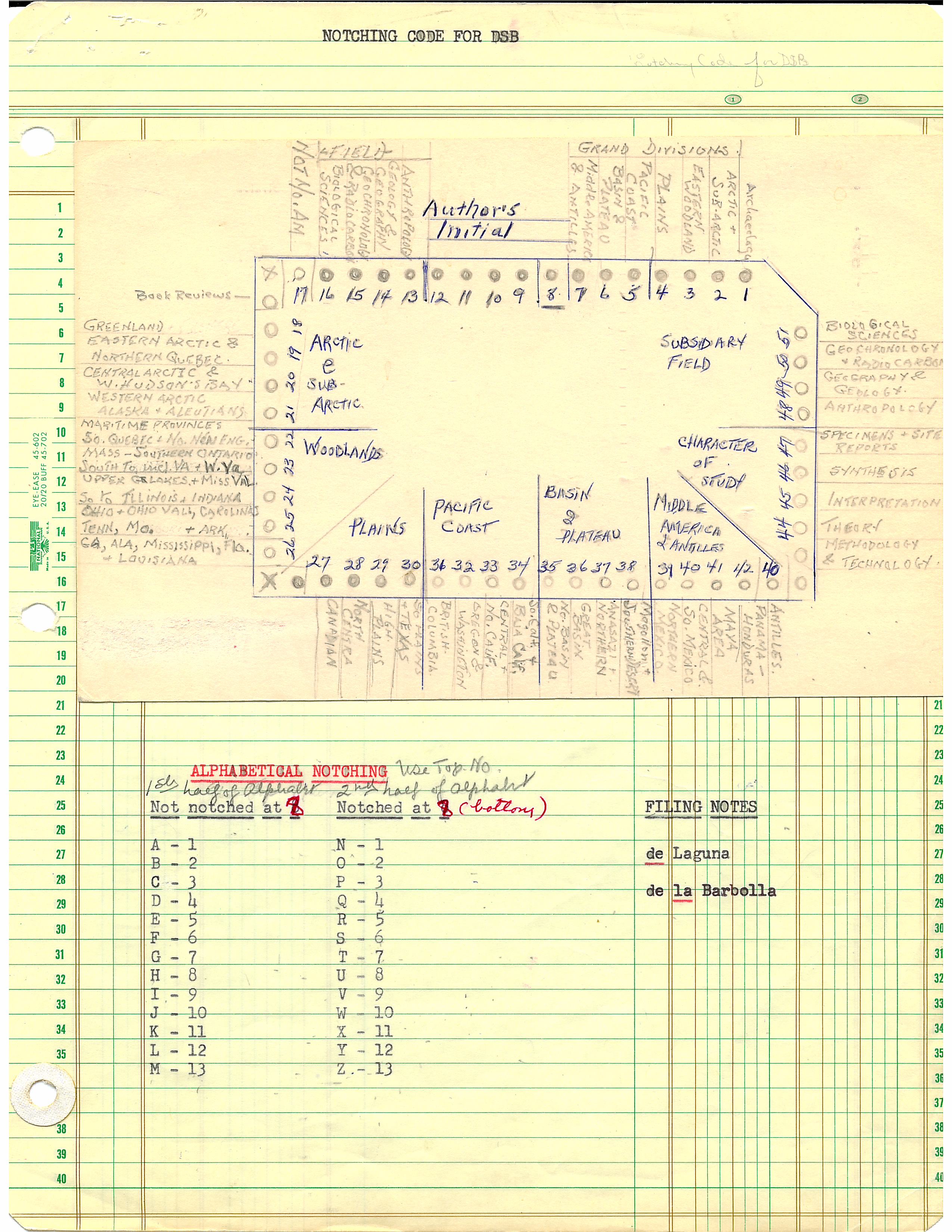

Radiocarbon dating techniques utilized by MacNeish in Tamaulipas and Tehuacán required large amounts of carbon, frequently charcoal, that would be destroyed during the dating process. The resulting age was then assigned to artifacts (corn, stone tools, bone, etc.) that were found in the same layer as the charcoal. Developments in radiocarbon made in the 1980s meant that much smaller samples were required, reducing the chance that sampled artifacts would be completely destroyed. When this direct method was applied to maize from Tehuacán and squash from Tamaulipas, the results were up to 2,500 years younger than previously thought.

The revisions resulted in prickly disputes about the age of domestication in the Americas. Eventually the dust up resulting from the new dating technique settled, due in part to new dates obtained from squash seeds that rooted domestication to an earlier date of 8,000 BC in Mexico.

MacNeish remained resolute that the dates he derived were accurate up until he passed in 2001. In 2012, Archaeologists returned to the cave sites in the Tehuacán Valley in search of maize remains. The team recovered new maize samples that corroborated the younger age for Tehuacán maize.

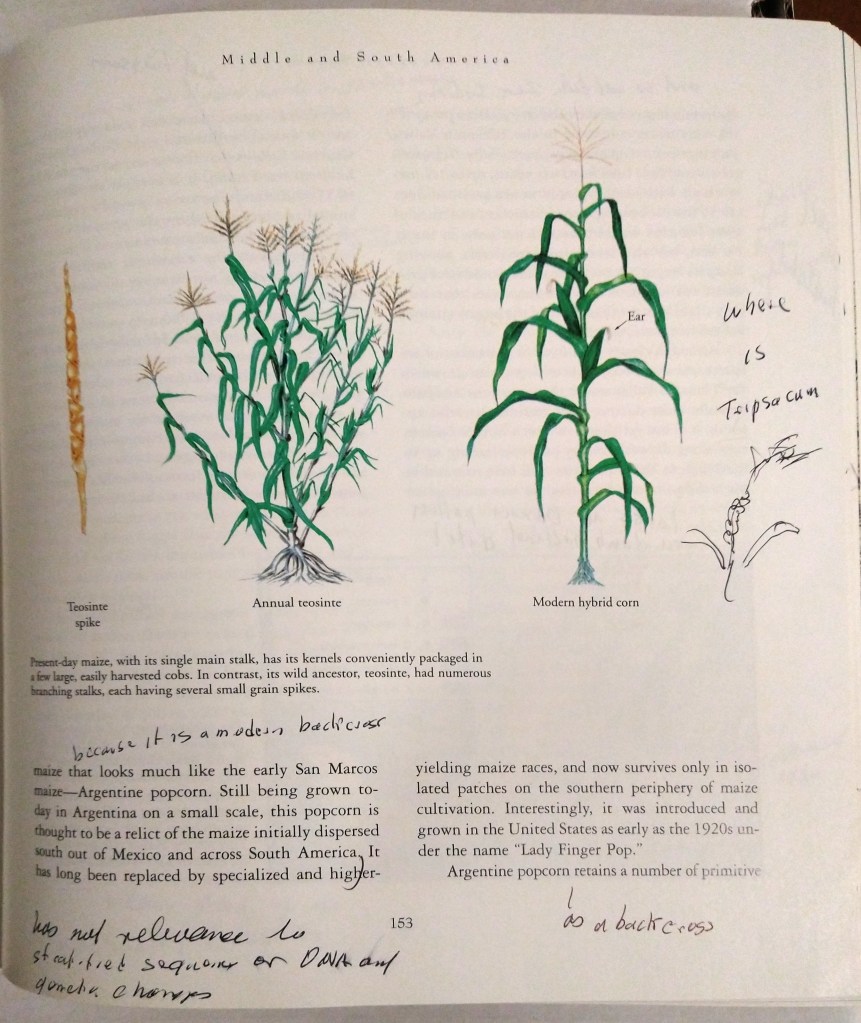

Recent research within the fields of microbiology and DNA have focused on the teosinte plant and the Balsas River as the probable ancestor and location for earliest cultivation of maize. Analysis of the DNA suggests that the plant was cultivated as early as 7,000 BC.

The fact that MacNeish did not locate the cradle of corn, shouldn’t take anything away from the massive effort he and his colleagues undertook during their search. As for the Tamaulipas maize, MacNeish himself credits his project in Tamaulipas for planting the seeds that would develop into the multidisciplinary approach he would adopt for much of his subsequent career.