Contributed by Lainie Schultz

On the weekend before Columbus Day in Columbus, Ohio, 1911, a group of Native American leaders and activists joined together to attend what became the first annual meeting of the Society of American Indians, or SAI. For the next thirteen years, this pioneering Pan-Indian organization was a center for Native American political advocacy, lobbying Congress and the then-Office (now Bureau) of Indian Affairs; offering legal assistance to Native individuals and tribes; publishing a quarterly journal; and corresponding extensively with Native Americans, “Friends of the Indian” reformers, political allies, and critics across the country.

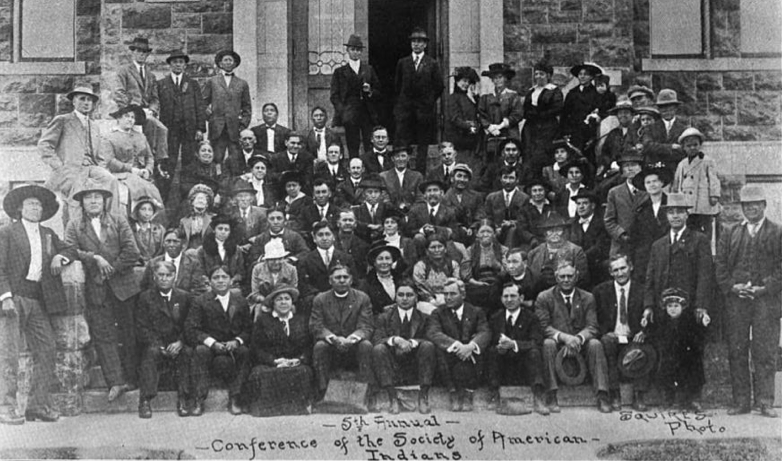

Members of the SAI were a veritable “who’s who” of early twentieth century Native history, representing activists, clergy, entertainers, professionals, speakers, and writers, from communities both on- and off-reservation. To namedrop just a few, these included (but were by no means limited to): attorney Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin (Métis/Turtle Mountain Chippewa/French); musician and writer Gertrude Simmons Bonnin (Yankton Dakota); educator Henry Roe Cloud (Winnebago); Episcopal priest Sherman Coolidge (Arapaho); civil servant Charles Dagenett (Peoria); painter and illustrator Angel De Cora (Winnebago); Episcopal priest Philip Joseph Deloria (Yankton Dakota); physician Charles Eastman (Dakota); author and linguist Laura Cornelius Kellogg (Oneida); ethnologist Francis La Flesche (Omaha); physician Carlos Montezuma (Yavapai Apache); writer, editor, and journalist John M. Oskison (Cherokee); archaeologist Arthur C. Parker (Seneca); lawyer Thomas Sloan (Osage); and advocate Henry Standing Bear (Lakota).

Without sharing a singular vision of Native American identity, tribal self-determination, or what the place of Native Americans should be within US society, these individuals committed themselves to a shared purpose, striving firstly “To promote the good citizenship of the Indians of this country, to help in all progressive movements to this end, and to emulate the sturdy characteristics of the North American Indian, especially his honesty and patriotism.” Seeking to benefit the freedom and development of all Native Americans, the two primary platforms on which the SAI stood were U.S. birthright citizenship for Native Americans and tribal access to the U.S. Court of Claims, addressing the two major issues at the forefront of public debates on the “Indian problem” at the time – the ambiguity of Native American legal status and the Office of Indian Affair’s mismanagement of Native lands and resources.

The investment of people’s time and unpaid labor in the work of the Society and its journal was extraordinary but ultimately unsustainable, and the SAI dissolved in 1923. Disappointingly, it had achieved neither of its major goals. Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, granting birthright citizenship to Native Americans but maintaining their wardship status. The Indian Claims Commission took over twenty more years to come, in 1946, allowing tribes to bring claims against the US government through judicial arbitration, not a court, and successful claims could result only in monetary compensation, not regained lands. The SAI also could not succeed in delivering a unified expression of Native American opinion to the government and public – probably the most unrealistic aim of all.

Despite its “failures,” the Society of American Indians was the first organization of its kind, created by Native Americans to amplify a Native American voice across the country during a time when people’s lives were under siege and they battled to have their voices heard on multiple issues. It may not have lasted long, but the SAI left a legacy of political, legal, and intellectual activism, setting the course for the many Native professional organizations to follow, and standing as part of an ever-present, ongoing continuum of Native Americans advocating for their best interests; joining in the debate as to what that might look like or how to get there; and striving to build better, stronger, and healthier relationships with the rest of the nation.

Maybe consensus is less important than joining in the conversation. Whether you are celebrating Columbus Day, commemorating Indigenous Peoples’ Day, or just slogging through another Monday – that door is always open.