Contributed by Emma Lavoie

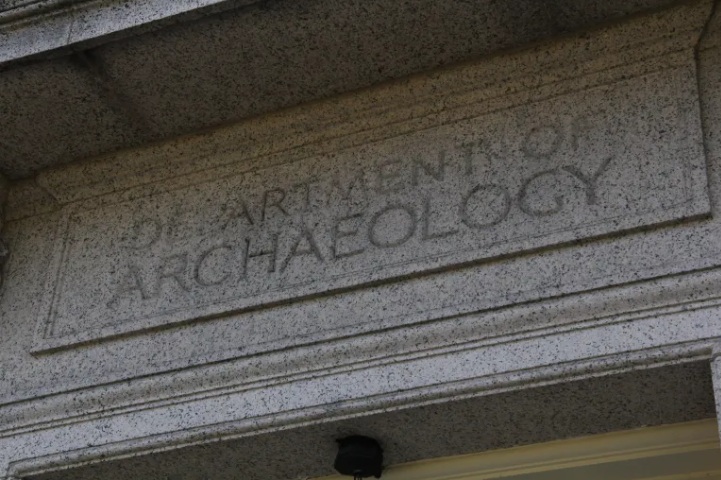

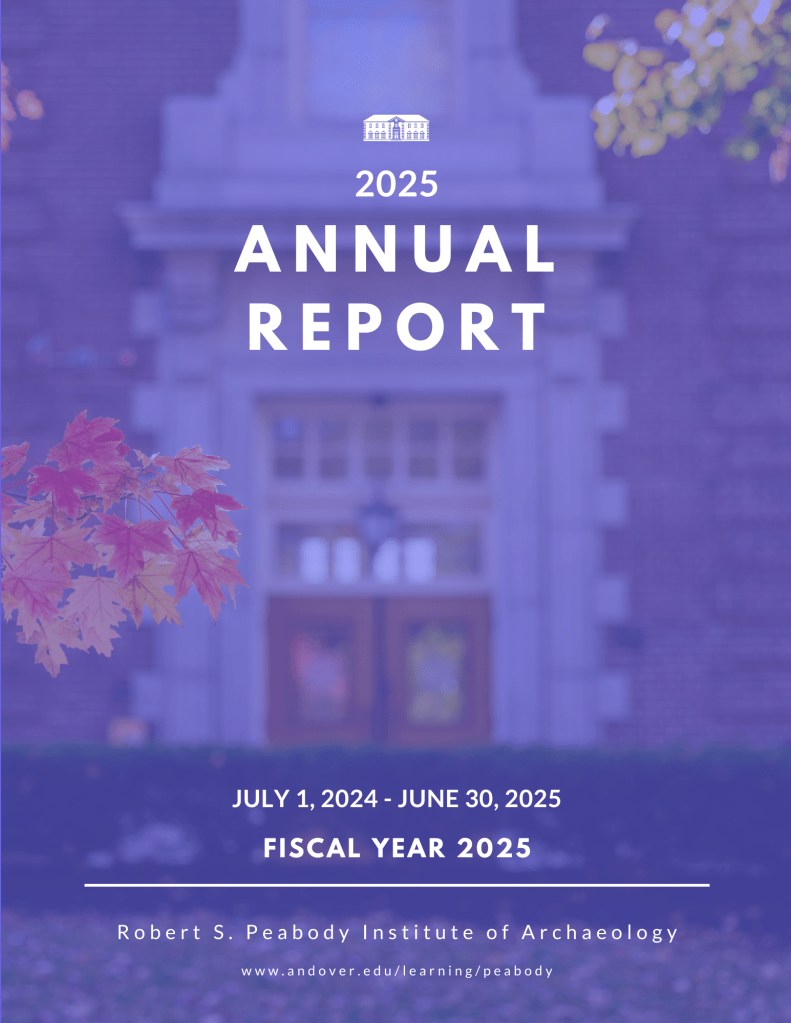

We are just over a month away from celebrating the founding anniversary of the Peabody Institute of Archaeology (originally known as the Department of Archaeology) at Phillips Academy Andover. This year marks a special milestone for the Peabody, being our 125th Anniversary, that’s quasquicentennial if you’re fancy!

This blog celebrates the founding history of the Peabody as captured by Phillips Academy’s student newspaper, The Phillipian, and acts as a “save the date” for more ways to celebrate with the Peabody throughout the year.

On Thursday, March 21, 1901, the Trustees of Phillips Academy established the Department of Archaeology at a meeting held in Boston. An anonymous donor and friend of the Academy, “provided a foundation sufficient for the erection of a suitable building, an endowment for instruction, research, and publication, together with a large collection.”

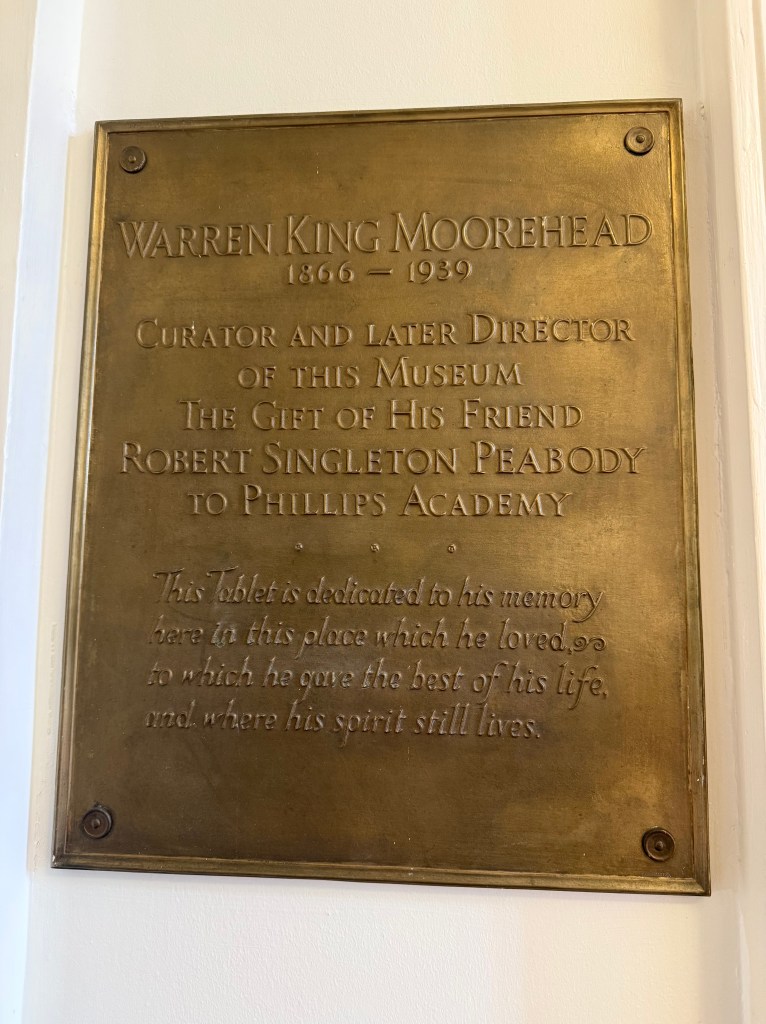

The inaugural officers of the Department of Archaeology were Dr. Cecil F.P. Bancroft (Principal of Phillips Academy), Charles Peabody (first Peabody Director), and Warren K. Moorehead (first Peabody Curator and Chief Executive Officer of the Archaeology Department).

In later years, the anonymous donor was recognized as Phillips Academy alumnus, Robert S. Peabody (Class of 1857), the namesake of our institution. Peabody’s passion for archaeology led him to create the archaeology program to encourage young students’ interest in archaeological sciences and to foster respect and appreciation for Native American culture. In addition, the institution would support archaeological research and serve as a place for students of Phillips Academy to gather.

At the time (1901), this was the largest single gift to the Academy and included Peabody’s collection of nearly 40,000 items. It was not only rare but quite unusual for a preparatory school to have its own department of archaeology with international connections and a major collection.

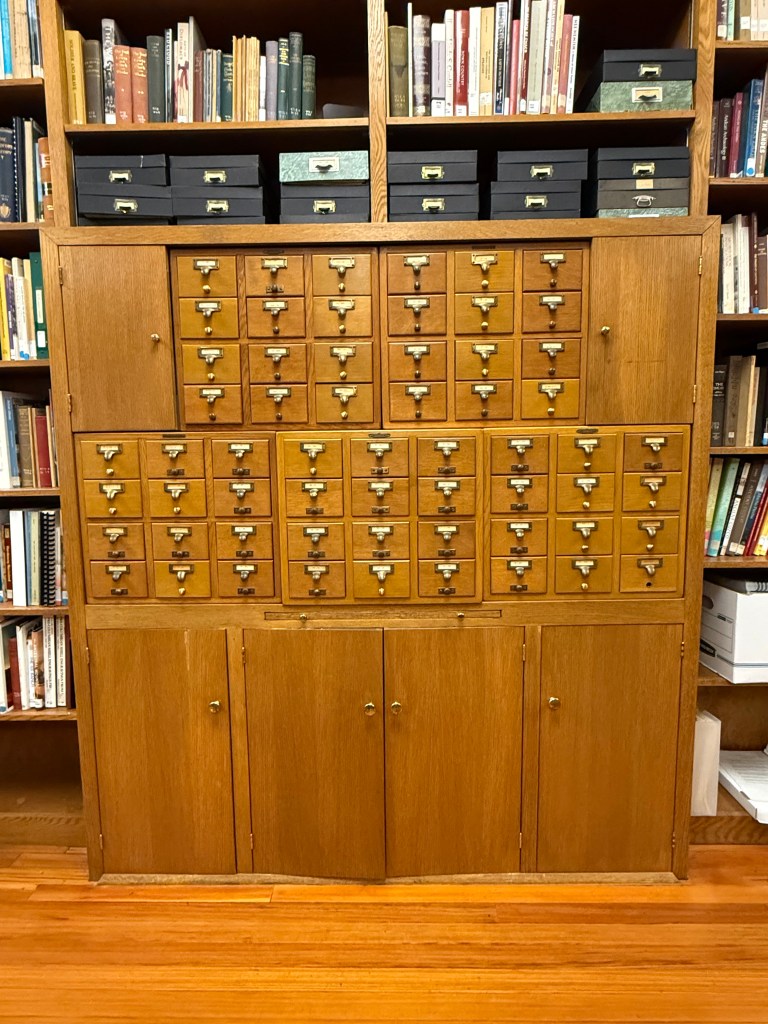

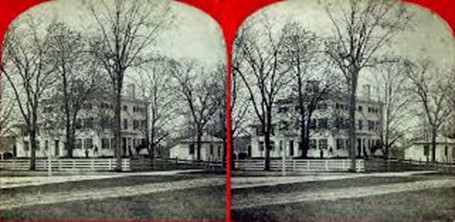

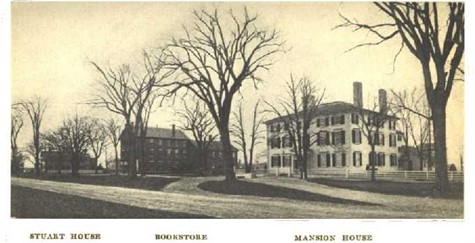

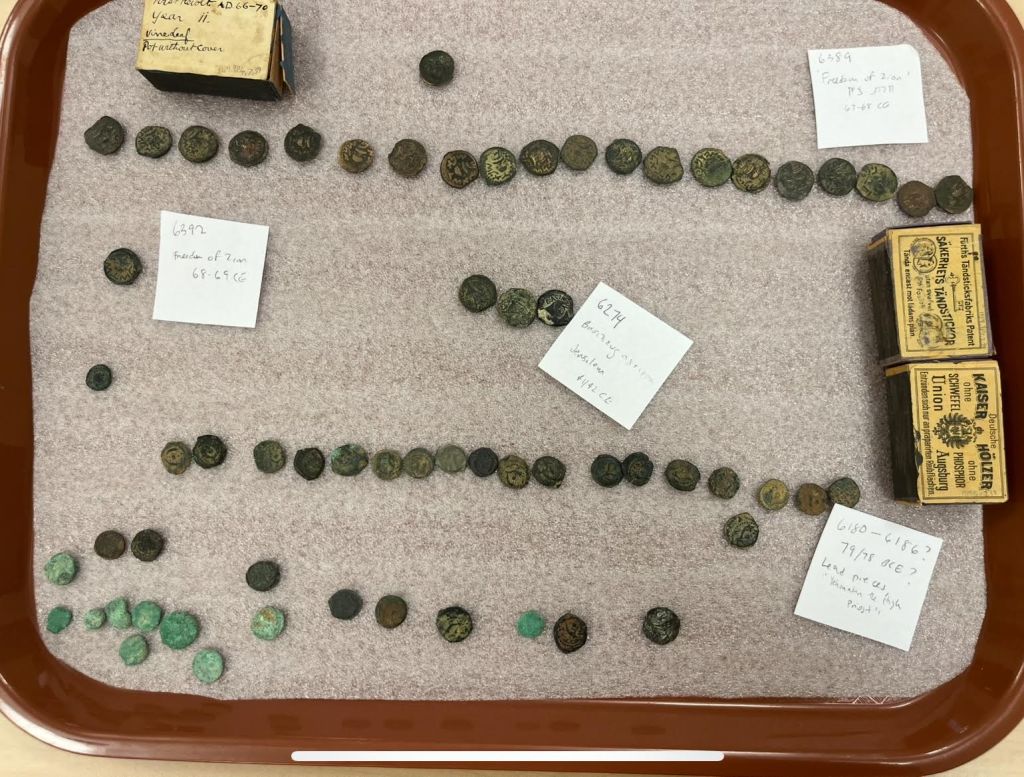

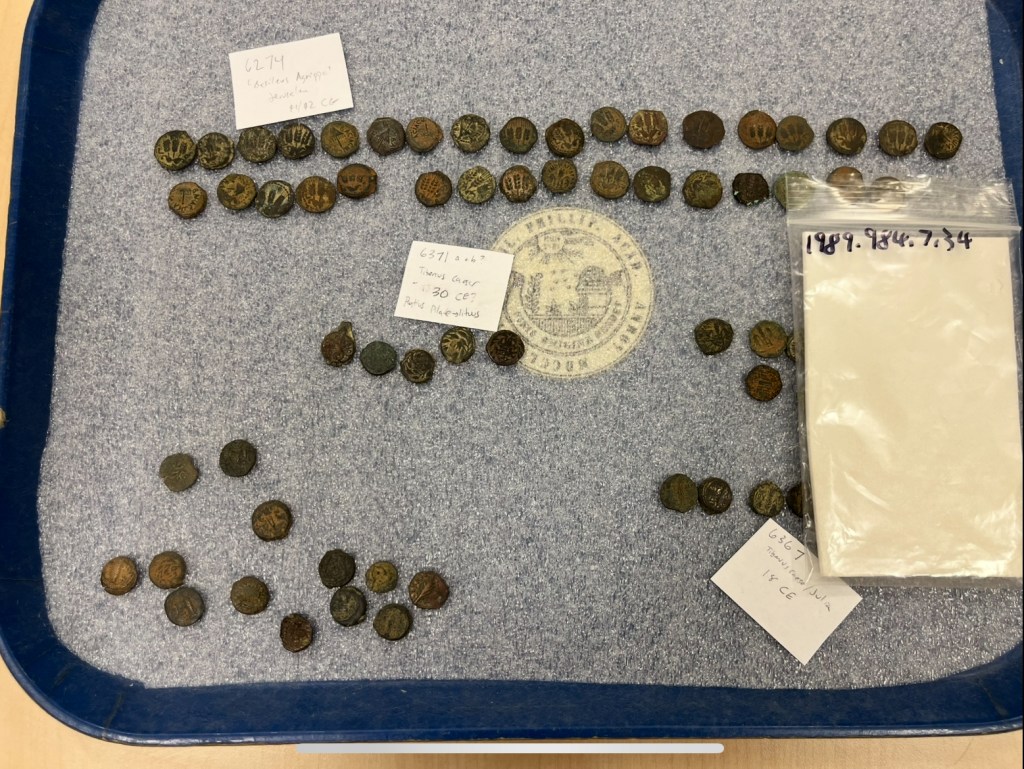

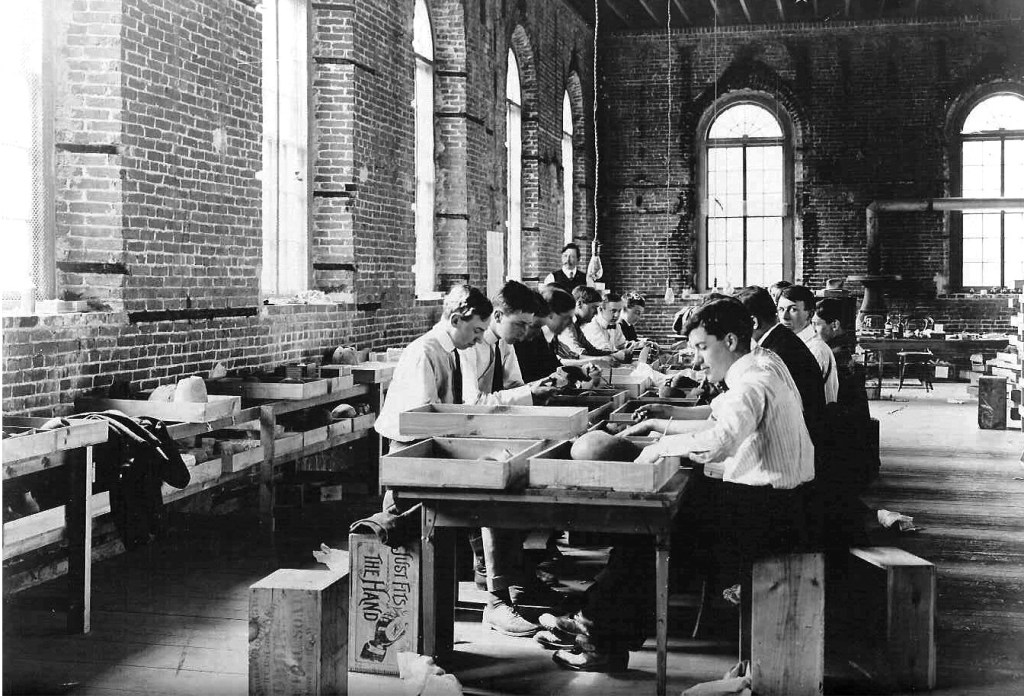

The new archaeology department was officially dedicated on Wednesday, May 1, 1901. Warren K. Moorehead spoke at a campus chapel meeting describing upcoming construction for the department and that a new building would be located on the corner of Phillips and Main Streets, where the current institute resides today. “The collection is now in Philadelphia and will be brought here [Phillips Academy] within the next two weeks and placed in the old gymnasium until the new building is finished.” Students from the Archaeology class would meet in the old gymnasium (located in the Brick Academy – the gym incarnation of Bulfinch Hall) on Monday and Thursday afternoons to help Mr. Peabody and Mr. Moorehead unpack the collection. The class met there for weeks while the new building was under construction, the laboratory-style work giving a unique replacement to the typical lectures students attended in their daily classes.

In the image above, students are unpacking from the very wooden drawers the Peabody used as housing for the collection, before it was replaced by more sustainable storage material in Phase 1 of the Peabody’s building project in 2023. If you look closely, you’ll see Mr. Moorehead standing in the background overseeing his students’ work!

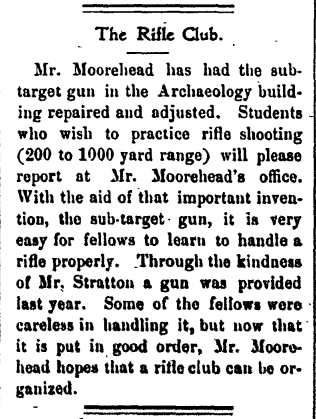

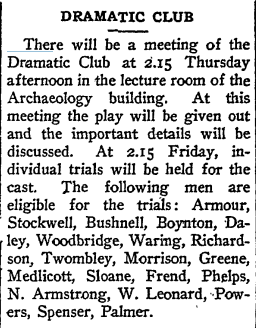

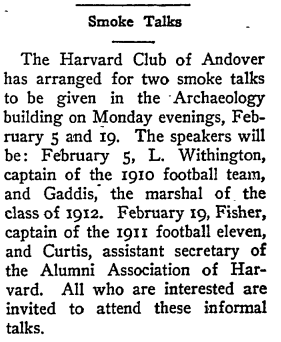

The first lecture in Archaeology was given by Charles Peabody on October 14, 1901. Lectures were shared between Peabody and Warren K. Moorehead, most taking place in other buildings on campus such as the science building while the Department of Archaeology was under construction. In addition, Moorehead would take students participating in the archaeology class to various sites in the area – examining shell heaps in Ipswich, MA and an Indigenous village site along the Merrimack River near Lawrence, MA.

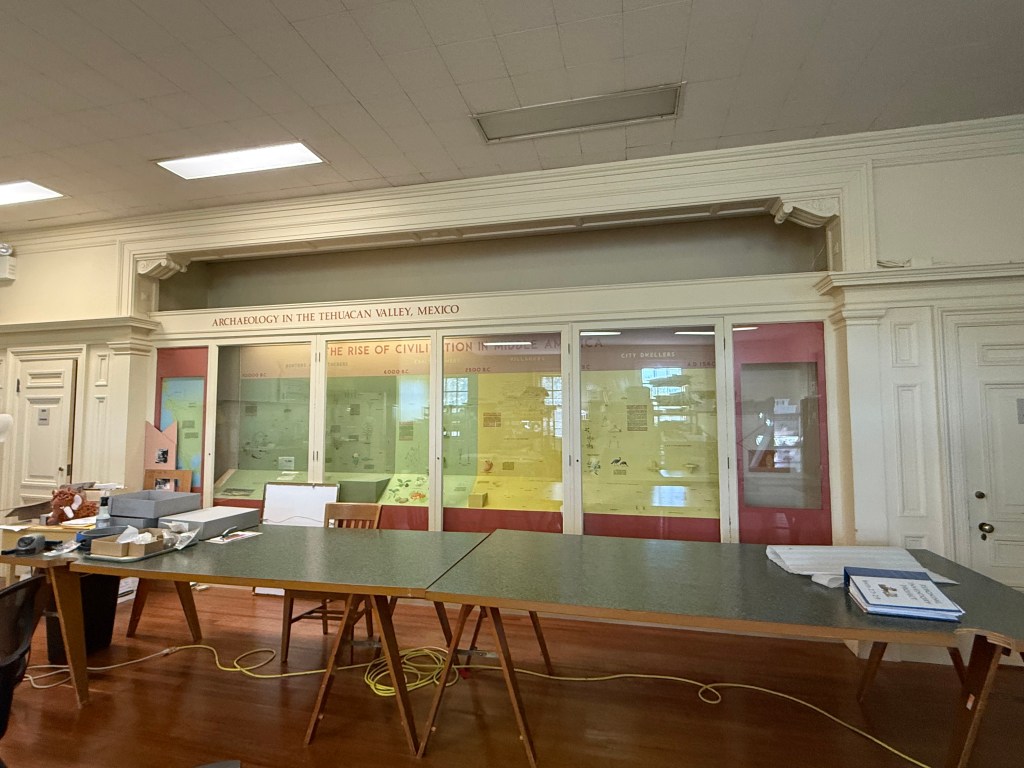

It is fascinating to see the parallels between current Peabody events and this moment in time – as of January 2026, the Peabody staff have moved out of the Peabody building to a temporary space across campus while the final Phase 2 of the Peabody’s building project begins. In addition, classes with the Peabody are (at present) being taught across other locations on campus during the building’s construction. With our Peabody Director, Ryan Wheeler, even teaching his Human Origins course in the science building as we saw Mr. Peabody and Mr. Moorehead doing about 125 years before!

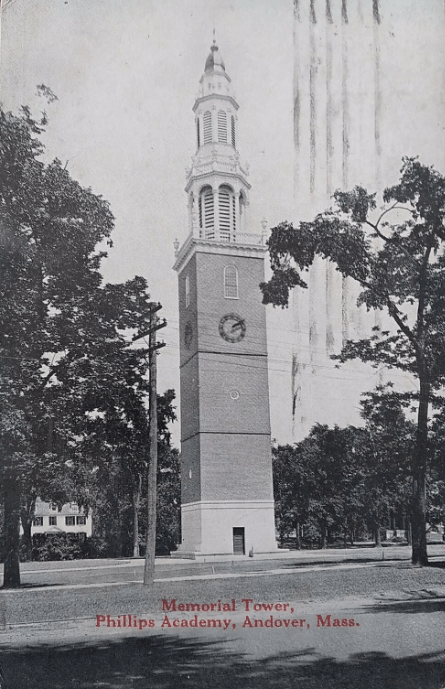

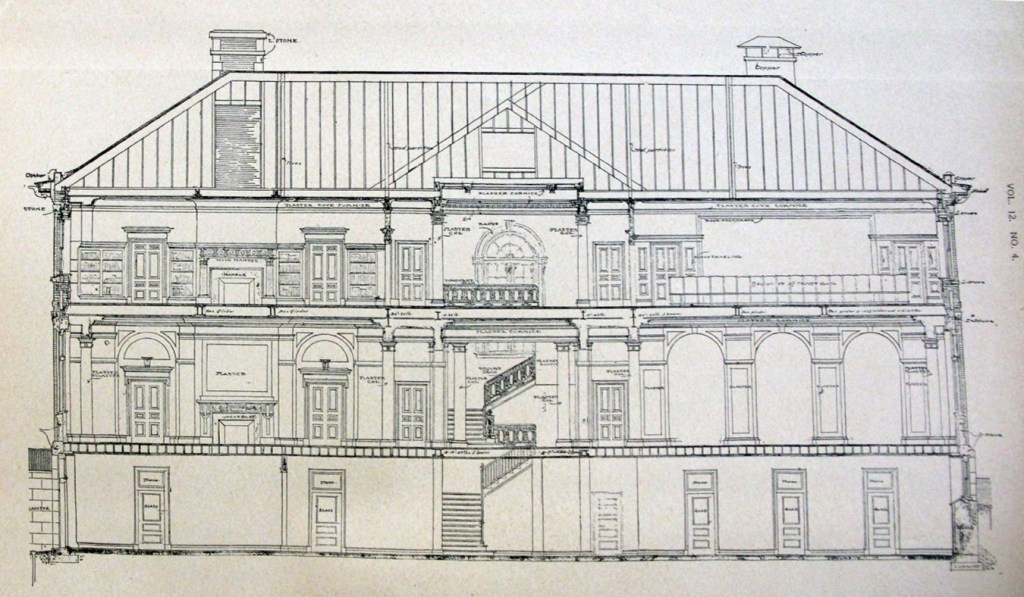

By October 30, 1901, bids for the new Archaeological building were in and construction was to begin soon after. Guy Lowell was chosen to design the building – the Peabody being his first architectural commission for Phillips Academy. Guy Lowell would later design other buildings on campus such as the Isham Infirmary (1913), Memorial Bell Tower (1922), and Samuel Phillips Hall (1924). Lowell also played a part in the development of the campus “Vista”, the reorganization of the Great Quadrangle, and renovations to Bulfinch Hall (1902). The Boston architect was most renowned for his design of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and New York State Supreme Court Building.

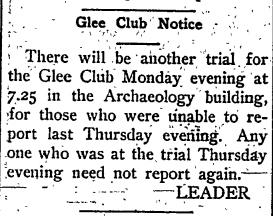

The building plans called for more than just a museum, detailing reception and meeting rooms “in which the students may assemble during recreation hours, both day and evening.” Spaces would be provided for the various clubs on campus as an informal gathering place.

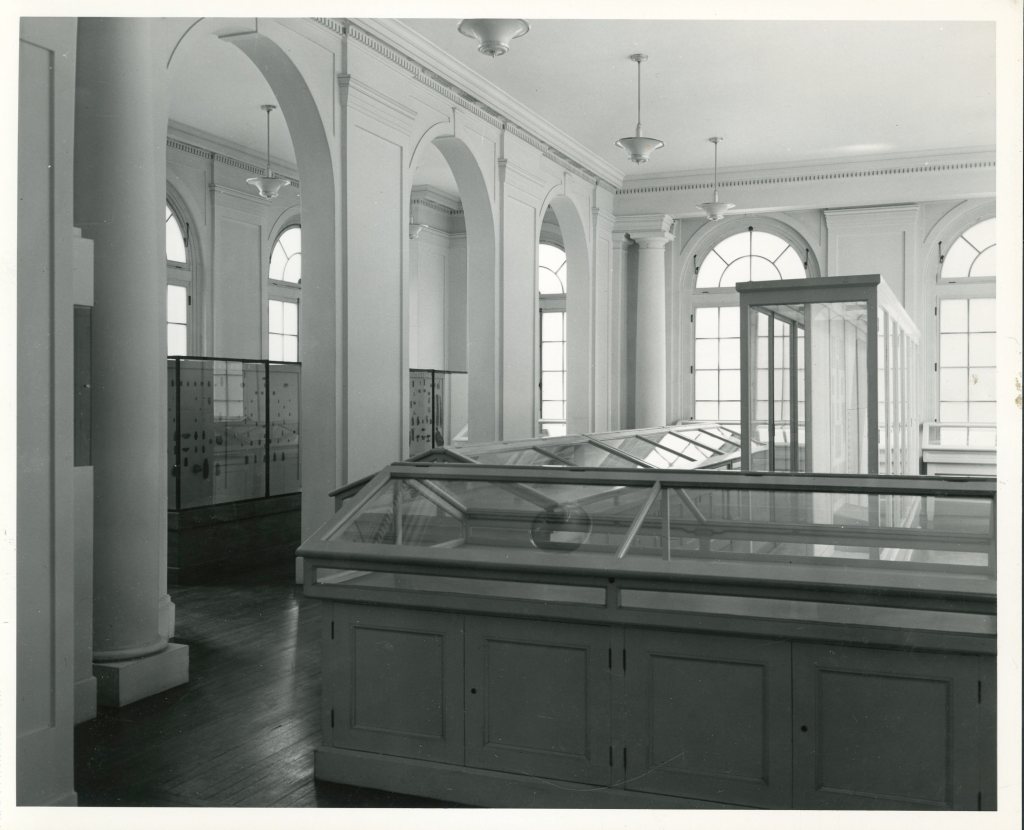

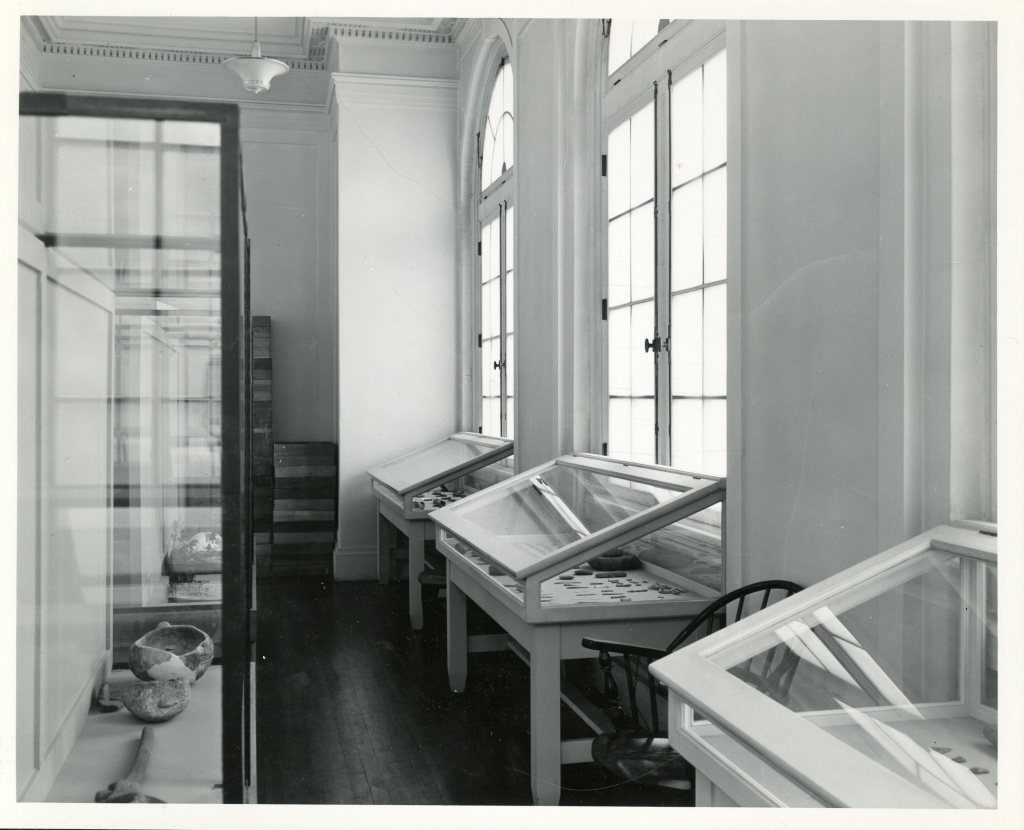

“The main entrance is in the center, opening into a spacious hall wherein the largest specimens in the collection can be shown. On one side of this hall is to be a big exhibition room, with an alcove, and on the opposite side is a similar hall, behind which are the custodian’s office and private apartments, and a cataloguing room.

The building is two stories. The second floor is given over to a room, on one side of the main hall, to be used for lectures and entertainment, with a large platform provided for these purposes. This hall will seat 175 or 200 students. On the other side of the main hall is a large library and reading room and lounging place, with a stack room, which will make it possible to care for 15,000 volumes. The windows on the lower floor are arched at the top, while those of the second are what architects term square headed.

The basement of the building is commodious, but will not be finished at once, although the plan is to have eventually an assembly room, a grill room, various committee rooms for the athletic departments, offices for The Phillipian and Mirror, and possibly a small cooperative store for the benefit of the students.”

-Excerpt from The Phillipian, October 30, 1901 Article.

For more details about some of the Peabody’s earlier building features, check out my previous blogs here and here!

As the new building construction began to reach completion, the Peabody collections were growing from various donations across the country. The archaeology department staff stored the collection in various parts of campus such as the old gymnasium (Bulfinch Hall), the new gymnasium (Borden Gym), and the Administration building (which alone, stored about 30 different collections, totaling to about 4,000 items.)

By early February of 1903, the Peabody collection was officially moved into the new building. Briggs & Allyn, a company in Lawrence, MA built fifteen large museum exhibit cases modeled after the Peabody Harvard Museum to display some of the collections.

I did appreciate the Peabody staff’s honesty at the time expressing the difficulties of balancing the move into the building with their academic responsibilities, mentioning “it has been difficult for the officials of the department to conduct class work properly, and for students to understand the course, since all the specimens have been inaccessible… all will welcome the installation of the collections in their proper quarters.”

The formal opening of the new Department of Archaeology building was held on Saturday, March 28, 1903. The opening was celebrated with a reception including performances by the Mandolin and Banjo clubs as well as several speakers from the Academy and Archaeological field. Out of the various addresses by members of the Academy, two stood out – one, from Dr. Robert R. Bishop (on behalf of the Trustees of the Academy) who most gratefully accepted the gift of the new building on behalf of the Trustees, regretting only that “on account of the modesty of the donor, he was not permitted to make known their name.” This being the very donor that we now honor as the namesake of our institution.

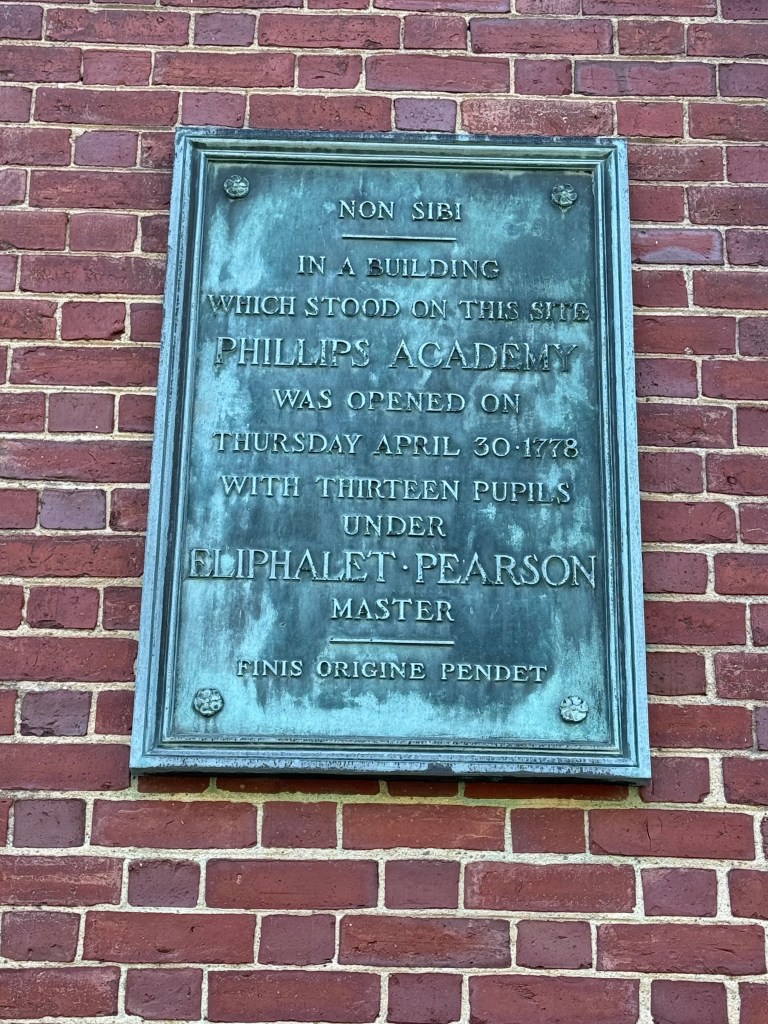

Second, from Vice-Principal A.E. Stearns (on behalf of the Faculty of the Academy) who mentions a very significant fact – “that one hundred and twenty-five years ago the first class that ever graduated from Phillips Academy, met for its exercises on the very spot where the new archaeology building now stands.” I find these words timely as the Peabody looks forward to celebrating 125 years in that same spot next month.

In commemoration of our 125th the Peabody will be celebrating all year with upcoming activities, events, special communications, virtual opportunities to connect with our institution, and ways to support the Peabody and our future projects. There is so much more to come that we cannot wait to share with you! Stay tuned and follow us on our socials so you don’t miss out on the festivities!

Instagram – peabodyandover

Facebook – peabodyphillipsacademy

Twitter – @RSP_Museum

Peabody Newsletter – Sign up here!