Contributed by Ryan Wheeler

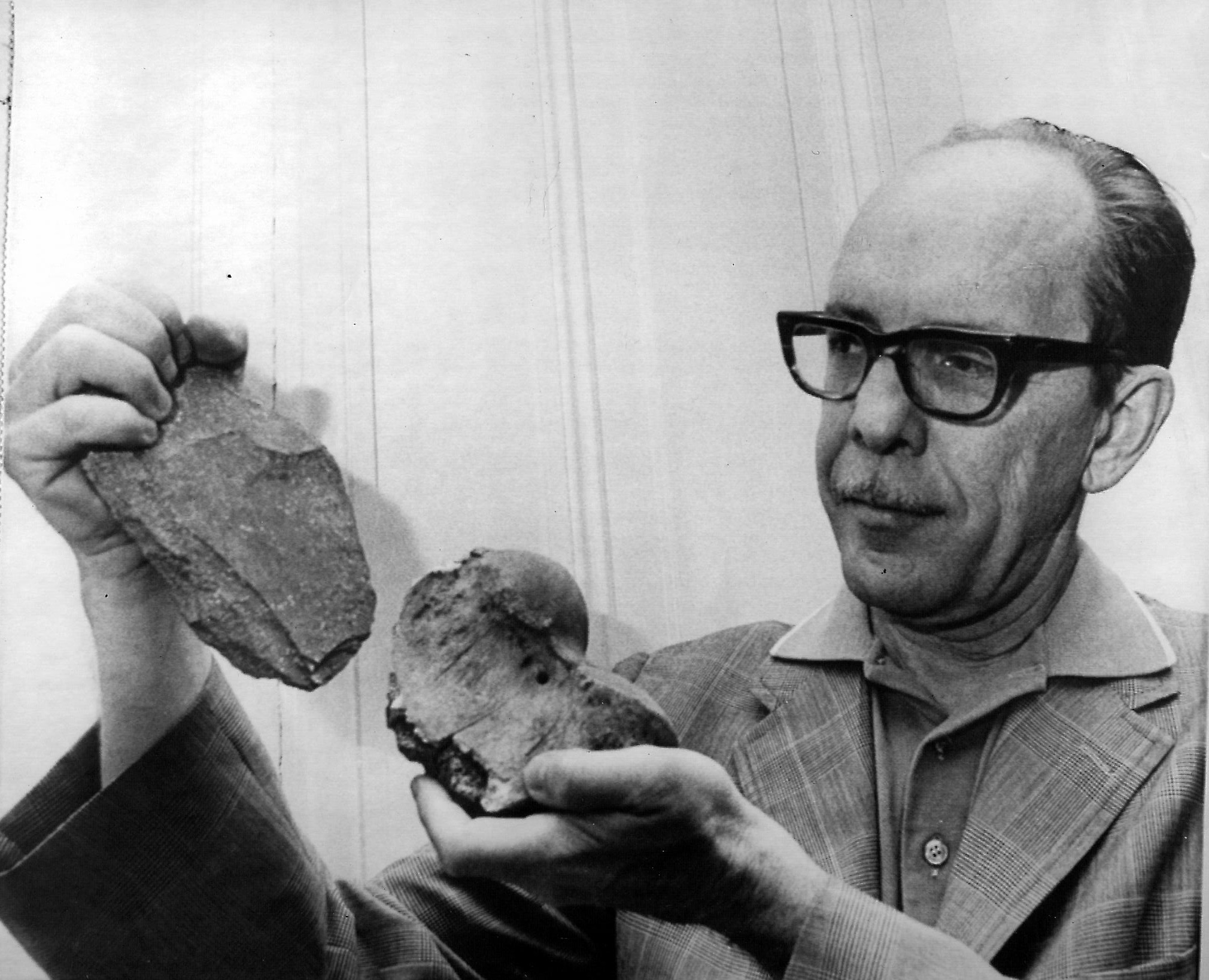

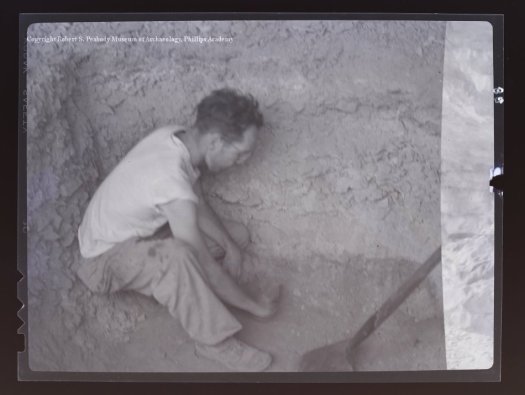

Early in his archaeological career Richard “Scotty” MacNeish, the Peabody’s fifth director, used funds from the Wenner-Gren Foundation to investigate caves and rock shelters in northern Mexico. MacNeish had found that some of these sites contained preserved plant remains, basketry, twine, and other perishable artifacts while a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Early in 1949 his crew chief discovered tiny corn cobs in La Perra Cave in the Sierra de Tamaulipas. The rich biodiversity of this area in northern Mexico, near the Gulf Coast and Texas border, had attracted other scientists interested in the flora and fauna of the so-called cloud forests. Perhaps it is not surprising that the ancient people of the area experimented with plants, including early crops like corn. MacNeish’s work in the Sierra de Tamaulipas pushed corn origins back to 4,500 years ago (about half of the now-acknowledged age).

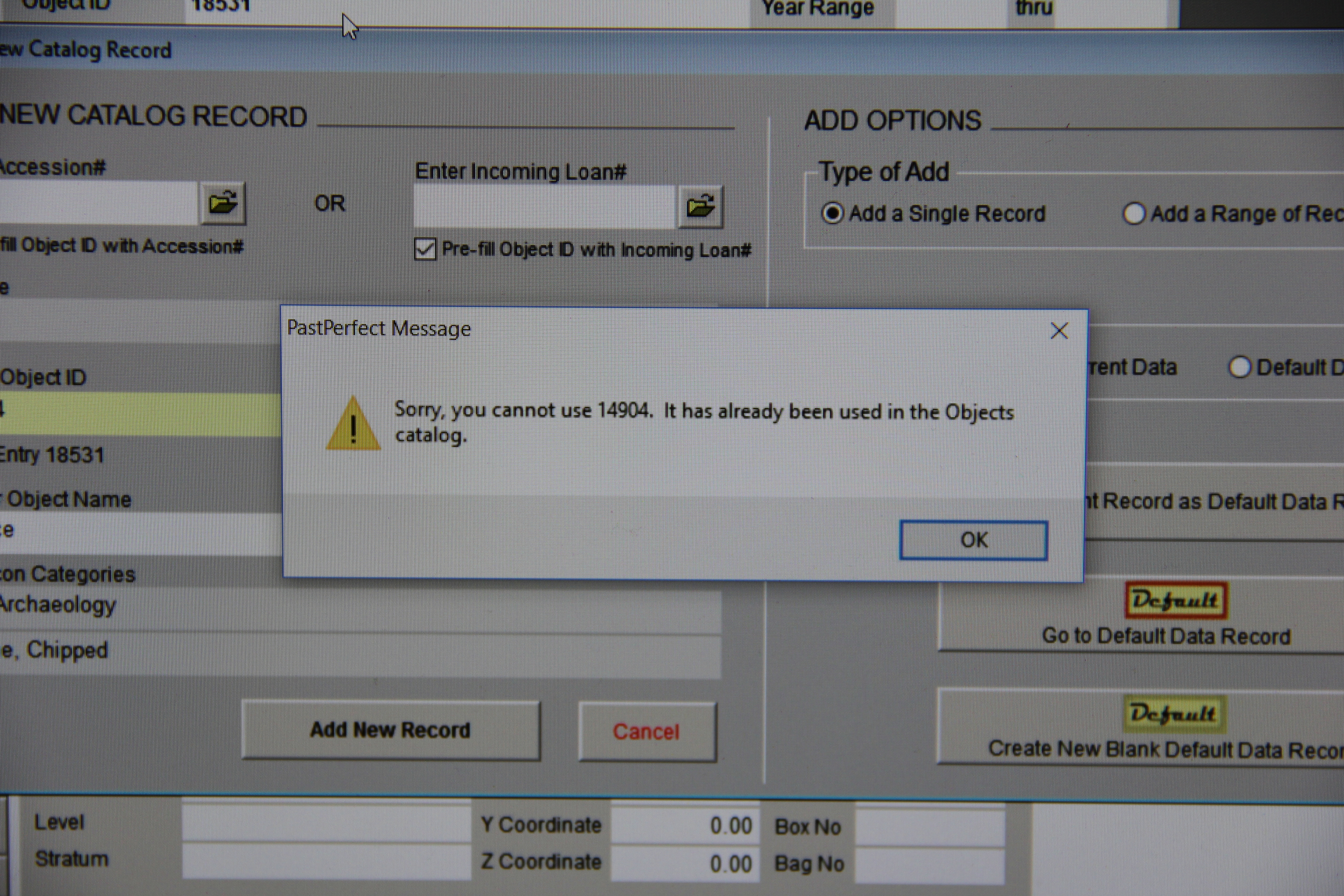

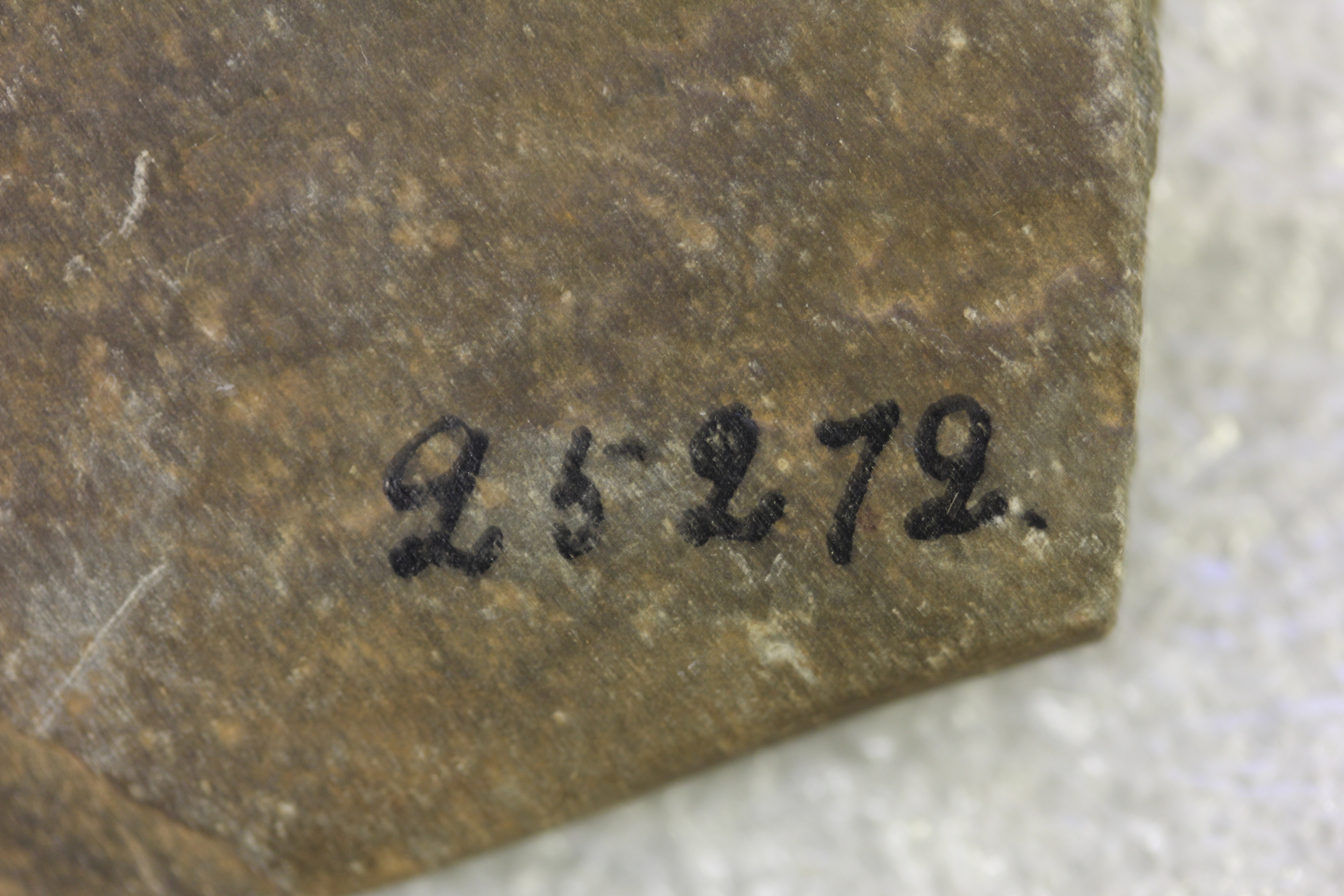

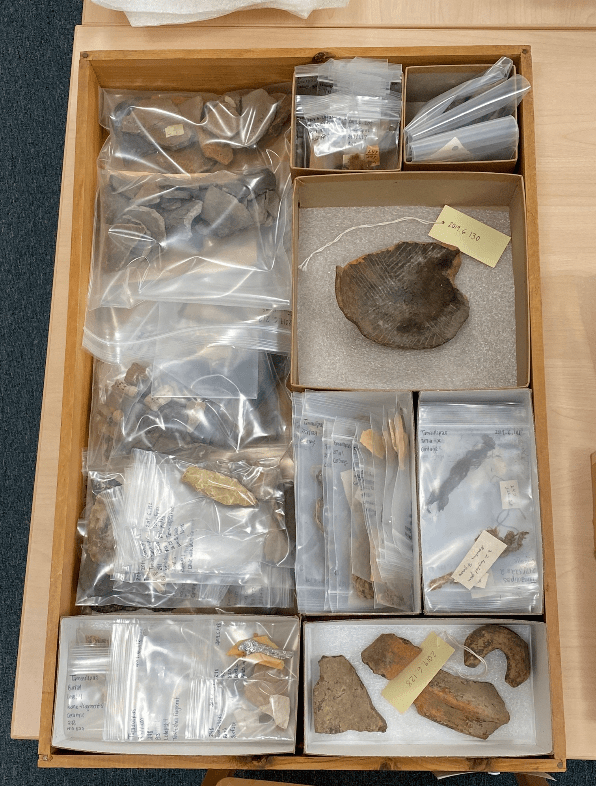

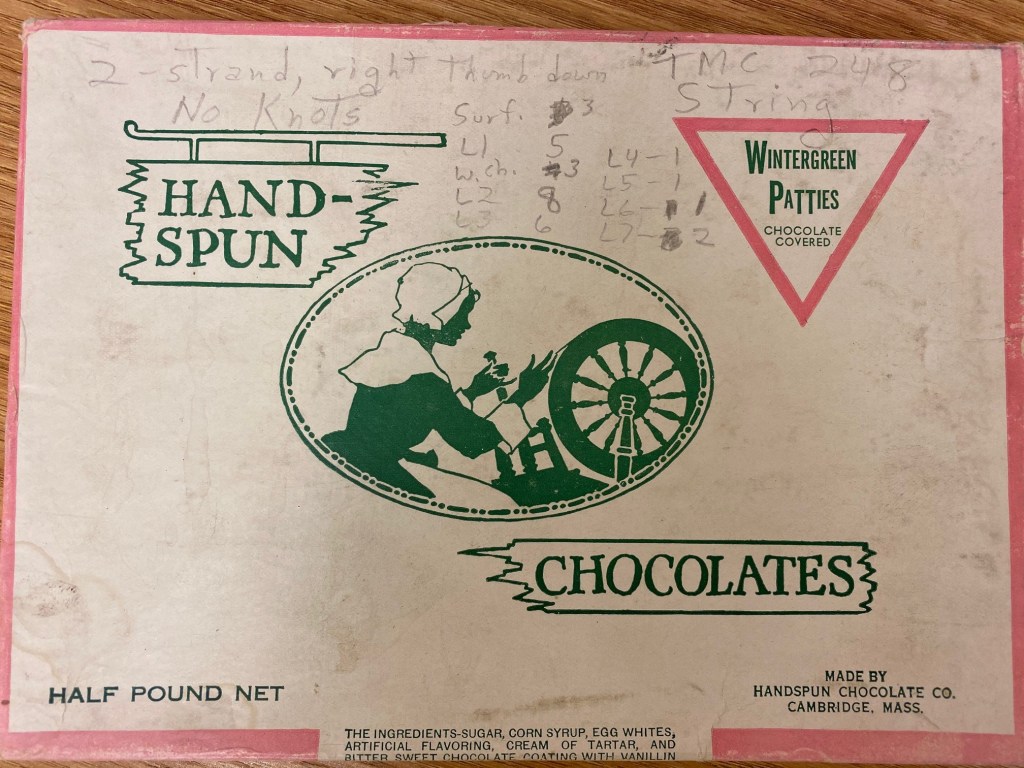

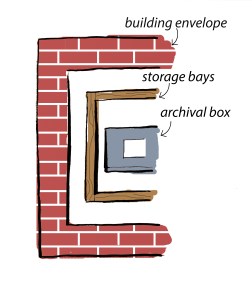

The Peabody houses a small type collection of materials from MacNeish’s work in Tamaulipas, including artifacts, photographs, and fieldnotes. Last year we collaborated with the Boston Public Library’s Digital Commonwealth project to digitize the archival records associated with MacNeish’s Tamaulipas project, primarily to facilitate access by Mexican archaeologists working in the region. Those files are available on InternetArchive. We also digitized many of the photos from the project, available via PastPerfect Online. Recently, Peabody staff member Emma Lavoie has been cataloging the artifacts from Tamaulipas. Looking over Emma’s shoulder one day at the many preserved plant remains, I was surprised to see part of an ancient orchid!

The Orchidaceae are one of the largest families of flowering plants, known to most of us from the cultivated examples with colorful and fragrant blooms available at grocery stores and garden centers. Commercial growing of orchids as houseplants began in the nineteenth century as the demand for “parlor plants” increased and diverse hybrids were created, many with fantastically shaped and colored blooms. Most of the orchids available for sale are of the genus Phalaenopsis. In the wild there is considerable diversity too, with terrestrial and epiphytic examples and a range of shapes, sizes, colors, and scents. Perhaps the best-known orchid is vanilla, a terrestrial form from Mexico.

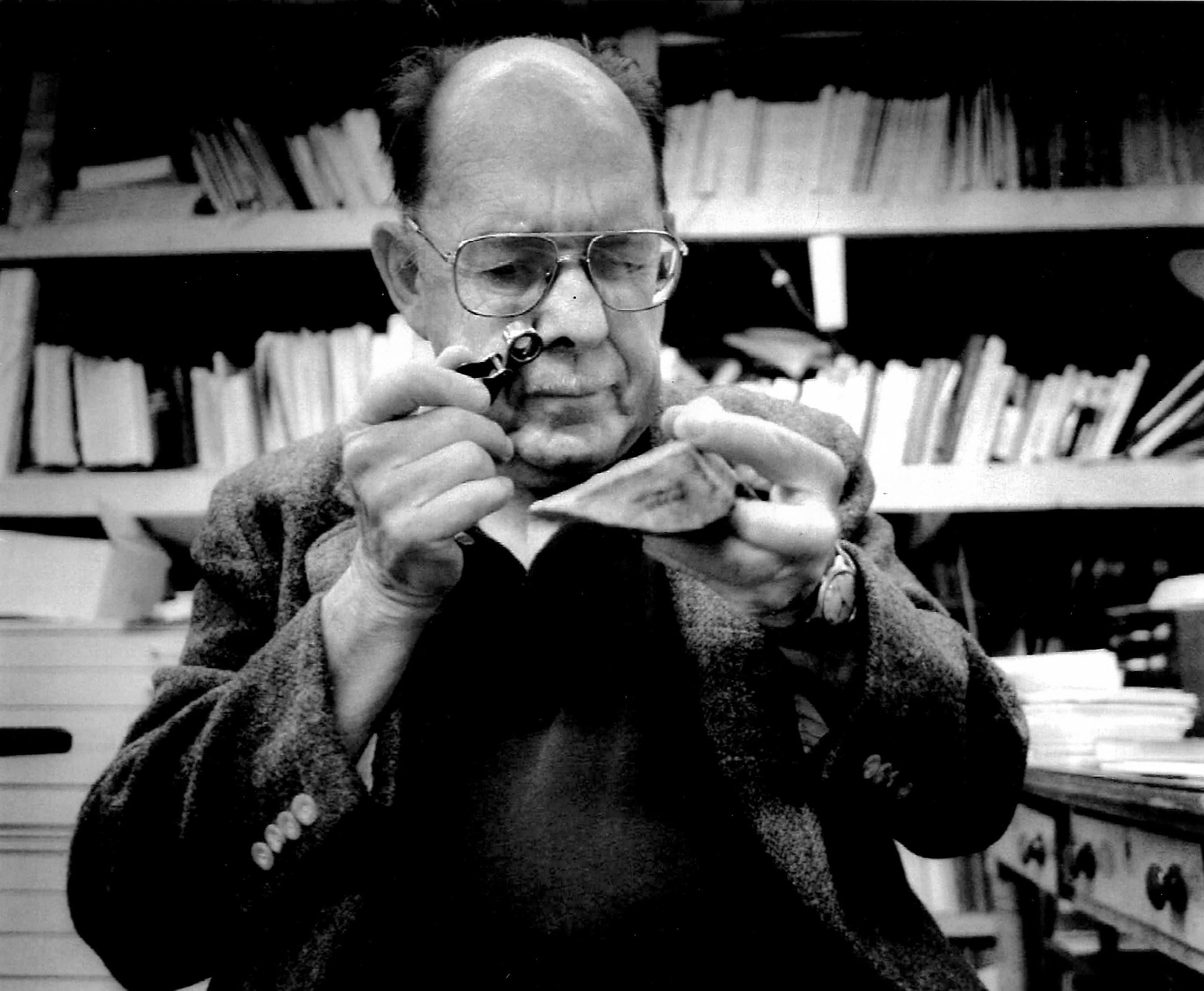

We do not know what genus or species the dried pseudobulbs and roots of the Tamaulipas orchid represent. Notes on file show that botanist C. E. Smith, a student of Paul Mangelsdorf at Harvard, identified the orchid. Mangelsdorf worked closely with MacNeish on his early corn project, and Smith pioneered the field of archaeological botany. Quick searches of the literature did not reveal many examples of archaeological specimens of orchids in the Americas. We do know from some of the few preserved screen-fold books made by the Mixtec, Aztec, and their contemporaries that a variety of orchids were used in medicine, some may been collected for their hallucinogenic properties, and others were used to produce a special glue used in featherwork.

Carlos Ossenbach, in his 2005 study “History of the Orchids in Central America, Part 1: From Prehispanic Times to the Independence of the New Republics,” laments that the destruction of the majority of the screen-fold books by the Spanish also destroyed considerable information on the use of orchids in Mesoamerica. Between 1547 and 1577 Bernardino de Sahagún compiled his History of Things of New Spain (also called the Florentine Codex), which includes considerable information on the use of plants, including orchids, among the Aztec. Here Sahagún documents the use of the Encyclia pastoris orchid for glue making, when he describes how the pseudobulbs of the orchid are cut and soaked in water to produce a sticky substance called tzacutli. The complete codex can be viewed online: https://www.wdl.org/en/item/10096/view/1/35/ Researchers have documented at least twenty-three different orchid species and their use by the Aztec, Maya, and their neighbors, primarily as medicines, adhesives, fixers for pigments, and as ornamental specimens.

The Tamaulipas orchid reminded me of the many terrestrial and aerial orchids that we often encountered at archaeological sites in Florida. Limestone and shelly soils encouraged their growth. It also brought back memories of my work at the Miami Circle site in late 1999. During the fieldwork I stayed with my parents and I was fortunate to accompany my mom on an orchid ramble one Saturday. A bus packed with orchid enthusiasts left Fort Lauderdale and visited at least half a dozen orchid growers in Homestead and Redlands, south of Miami. During the ramble we entered a raffle. I was surprised to receive a call Sunday evening. The gentleman calling informed me I had won a raffle prize and asked if I could collect it after work on Monday. After another intense day at the Miami Circle I navigated my Ford F-150 long-bed pickup through Miami’s crowded streets, onto Florida’s Turnpike, and then onto the Homestead extension. It was dark by the time I found the orchid grower. We entered the massive greenhouse and the grower–the gentleman who had called me the night before–gestured to one of the tables covered with orchids. I assumed I had won one of the orchids. He corrected me in a mellifluous English accent, I had won ALL of the orchids on the bench, approximately 100! He helped me load them into the F-150 and I headed north. My parents were disbelieving upon my return home. After I persuaded them to come outside, however, they acknowledged the enormity of the prize. My dad helped me unload and we struggled to find room in my mom’s orchid shade house. Some are still thriving today, while others were lost to hurricanes.

I’m interested in our Tamaulipas orchid. Could we determine the genus and species? Would that help us better understand why the orchid was in a cave deposit? Maybe as a drug, or for glue making, or as a mind-altering hallucinogen? Perhaps we can connect with a specialist and answer some of these questions!