Contributed by Ryan Wheeler

As we prepare updated Native American Graves Protection & Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) summaries and the required notices following claims and decisions about affiliation we are frequently confronted with the names of collectors. Some of these are quite familiar to us, Warren K. Moorehead, for example, who was our first curator and then our director. We recognize that the names of collectors often hold significant clues that may help make connections between now widely distributed holdings—what we refer to as “split and shared collections,” or aid in understanding localities or other entanglements. I’ve started developing short biographies of some of the collectors, with the hope that knowing when and where they were active might inform some of these other considerations. To develop the biographies, I usually rely on genealogical information to fill in birth and death dates, geography, personal and professional connections, and other details. Many of these collectors were in contact with Warren Moorehead and their names appear in his correspondence files or in his books, especially those volumes that highlight collectors and collections. In other cases, the collectors have some connection to our parent organization, Phillips Academy—either as students, alumni, or faculty. Here are a few recent biographies:

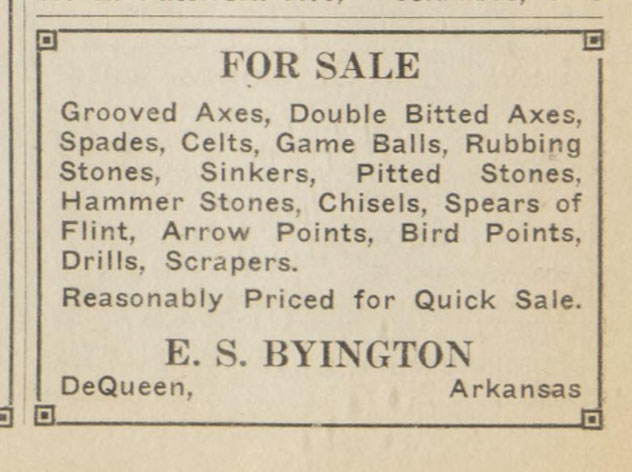

Edward Spencer Byington (often styled as E.S. Byington) was a civil engineer in DeQueen, Sevier County, Arkansas (1866-1941). He worked for several railroad companies, including DeQueen & Eastern. Byington often bought and sold artifacts, and his ads can be found in several publications—see for example, The Philatelic West (1926), and Hobbies, the Magazine (1931). One of Byington’s ancestors was Cyrus Byington, an early settler and missionary to the region, who had traveled to the area with Choctaw people being forced from their homes in Mississippi. E.S. Byington was an affiliate of Warren K. Moorehead and advocated for establishment of an “Association of Indian Relic Collectors & Dealers.” Correspondence with Moorehead indicates he was collecting artifacts during railroad construction and maintenance. Byington is listed as the source of at least 131 items in the Peabody Institute holdings.

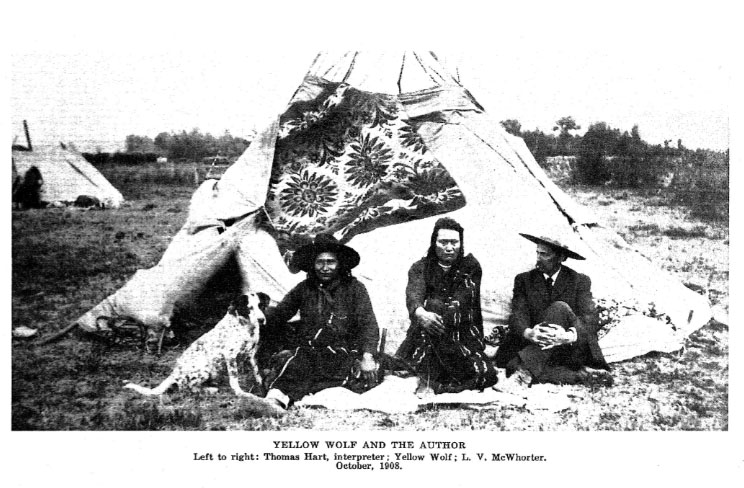

Lucullus Virgil McWhorter (often styled as L.V. McWhorter) was an American farmer and rancher, frontiersman, and writer who was a regular source of Native American material heritage for Warren K. Moorehead at the Peabody Institute (1860-1944). McWhorter compiled information on Indigenous communities and history of the Pacific Northwest, and is generally regarded as an advocate and ally of the Native American individuals and tribes that he worked with, including Yellow Wolf and the Nez Perce. See Washington State University for the McWhorter papers and finding aid, which frequently mention Moorehead: https://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:80444/xv98497. McWhorter is listed as the source of at least 507 items in the Peabody Institute holdings.

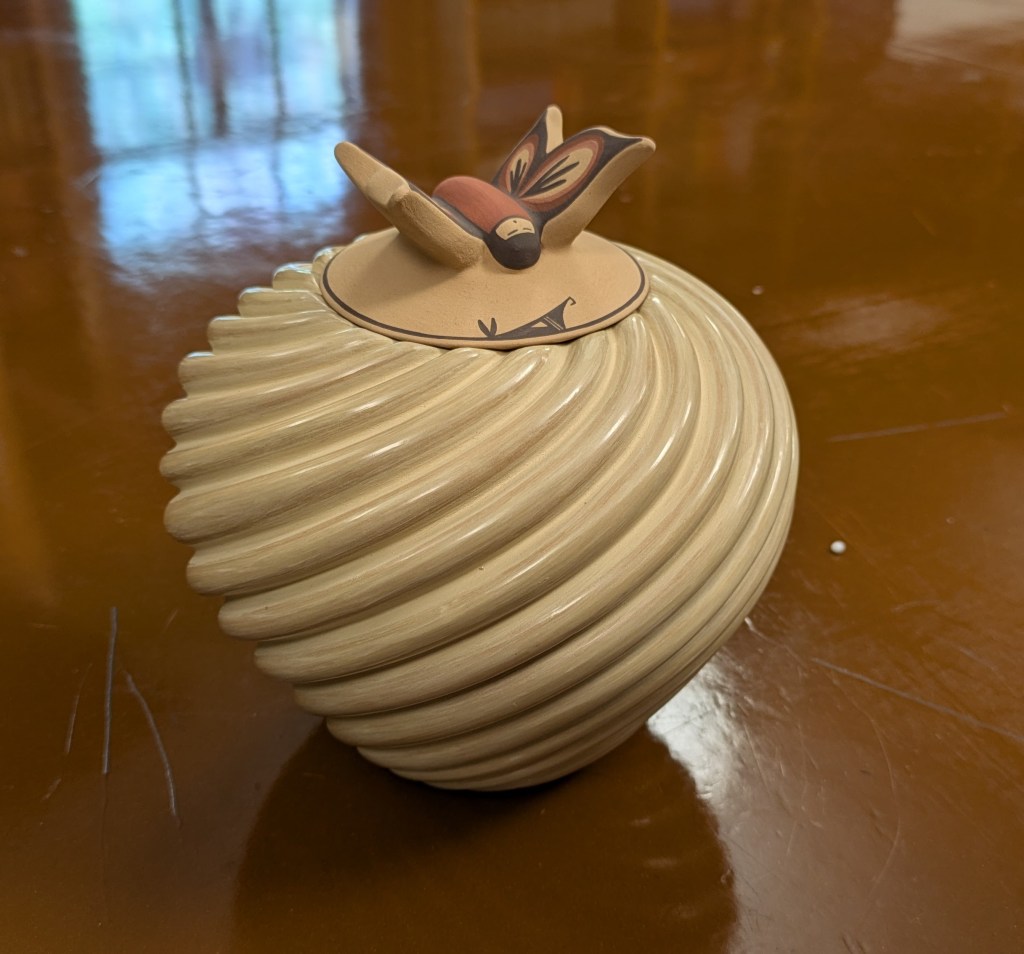

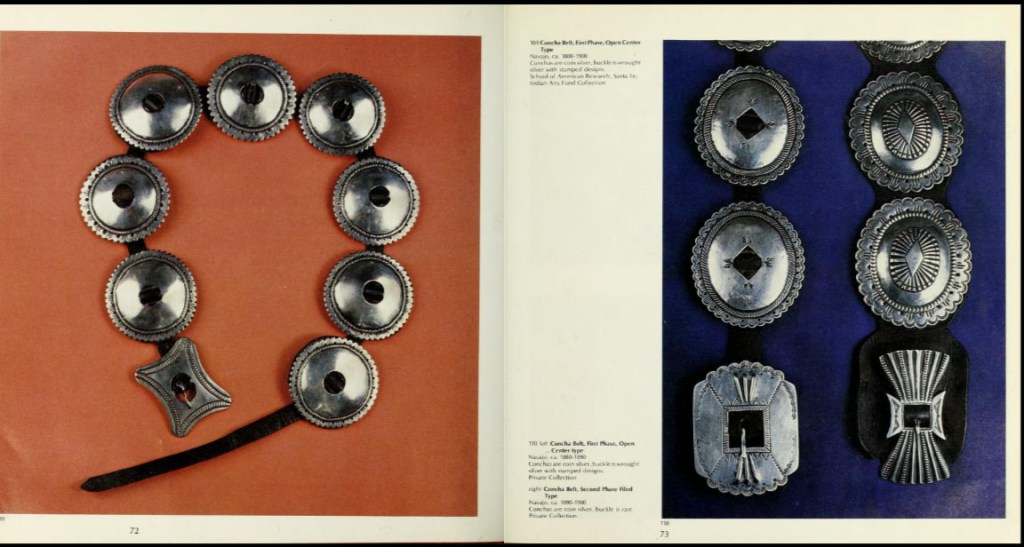

Donnelley Erdman (1938-2024) was a graduate of Phillips Academy (Class of 1956), an architect and instructor at Rice University. In 1978-79 he was involved in an exhibition of Southwestern material culture at the Aspen Center for the Visual Arts, Aspen, Colorado. See Philip M. Holstein and Donnelley Erdman (1979) Enduring Visions: One Thousand Years of Southwestern Indian Art, Aspen Art Museum (exhibit catalog). Erdman is listed as the source of at least 195 items in the Peabody Institute holdings.

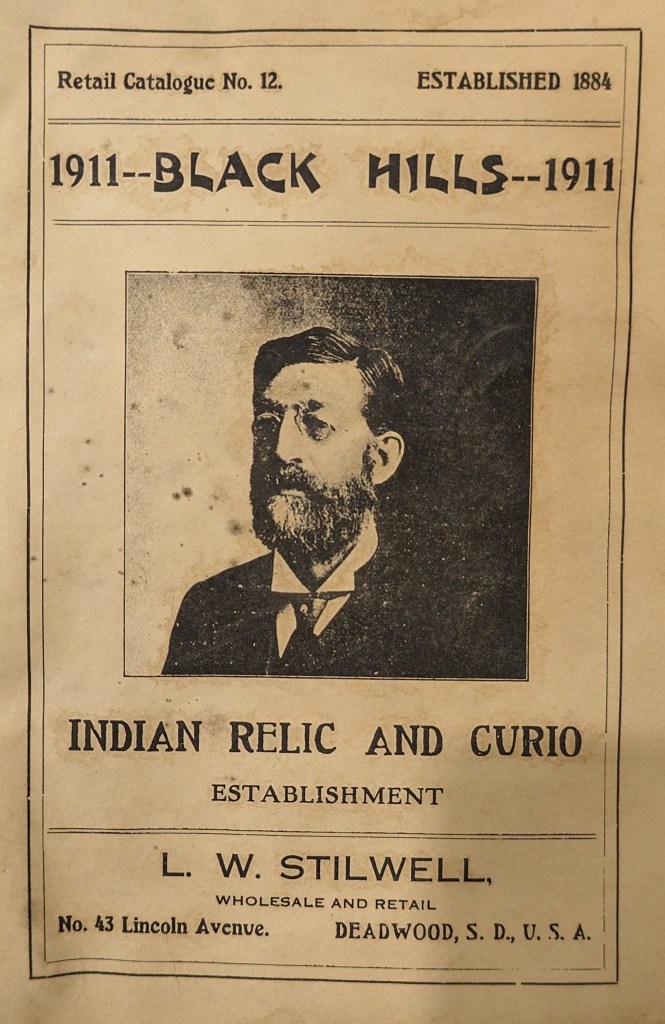

Lucien White Stilwell (often styled as L.W. Stilwell) was born in New York and grew up in Wisconsin (1843-1932). Following graduation from Ripon College, Stilwell moved to Cairo, Illinois and engaged in the grocery business. Throughout the 1860s and 1870s he was engaged in the grocery business via several partnerships, briefly worked for the Elgin Watch Company before relocating to Deadwood, South Dakota in 1879. In Deadwood, Stilwell was involved in banking, but it was here that he began to develop and expand his business in buying and selling Native American and natural history items. Throughout the 1880s he frequently advertised in collecting magazines, including Young Oologist, Mason’s Coin Collectors Magazine, The Agassiz Association Journal, The Museum, Hoosier Naturalist, The Philatelic West, and others, as well as short publications on geology. In the early 1900s he published catalogs advertising his “Indian Relic and Curio” establishment. He sold his business to Kenneth J. Crawford Company in 1928. Condensed from a longer biography by John N. Lupia III: https://www.numismaticmall.com/encyclopedic-dictionary-of-numismatic-philatelic-biographies/stilwell-lucien-white Stilwell is listed as the source of at least 18 items in the Peabody Institute holdings.