Contributed by Marla Taylor

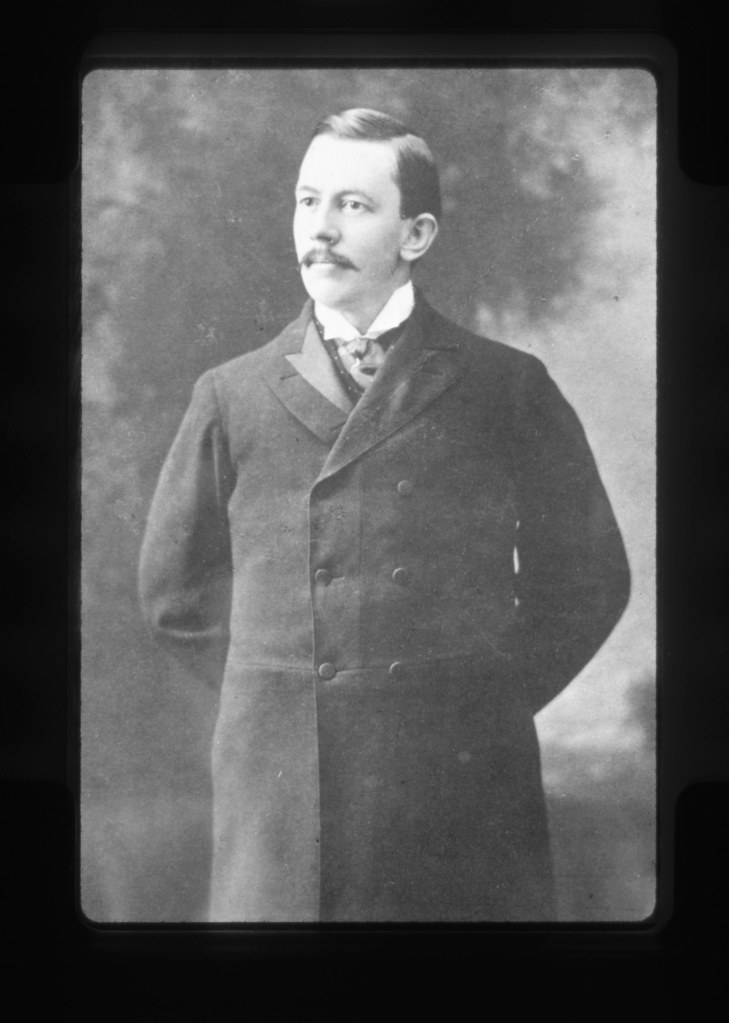

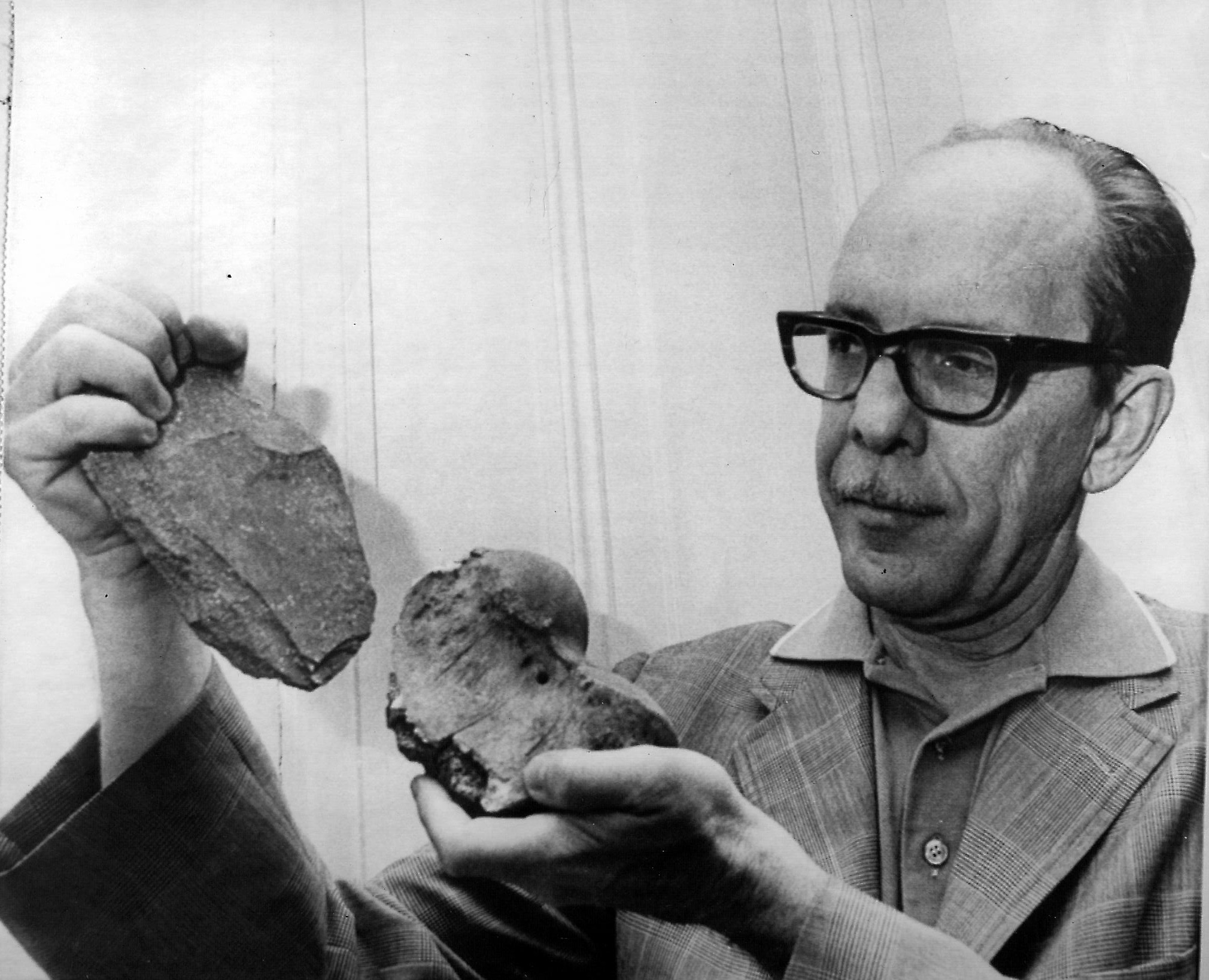

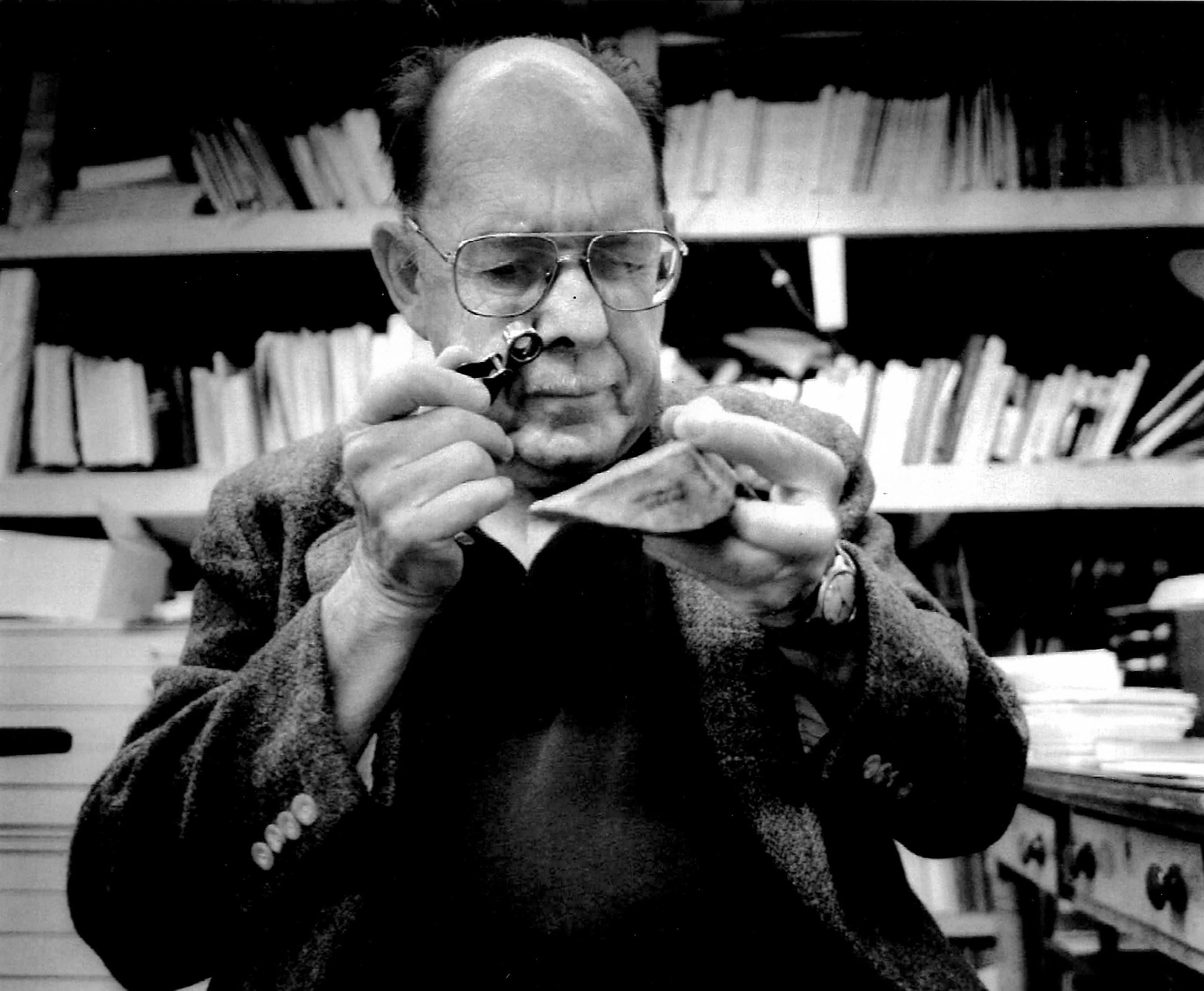

When thinking about the collections held by the Peabody Institute, I often also think of Warren K. Moorehead. Regular readers of the blog (I know there are a few of you out there!) are certainly familiar with his name and how tightly he is intertwined with the Peabody. To recognize Moorehead’s 155th birthday this week, I wanted to take a few minutes to share some of his story.

Warren King Moorehead (1866-1939) grew up in Ohio, where he cultivated a lifelong interest in archaeology and Native Americans. In his early career, he worked as a correspondent for The Illustrated American and served as the first curator of archaeology for the Ohio Archaeological Society (now the Ohio History Connection). In 1896, he began what would become a personal friendship with Robert S. Peabody, providing him with several Indigenous artifact collections. When Mr. Peabody chose to donate his collection to Phillips Academy in 1901, he appointed Moorehead as the first curator of the Department of Archaeology. Moorehead served in that capacity until 1924 when he then assumed the directorship. He finally retired in 1938, only a year before his passing.

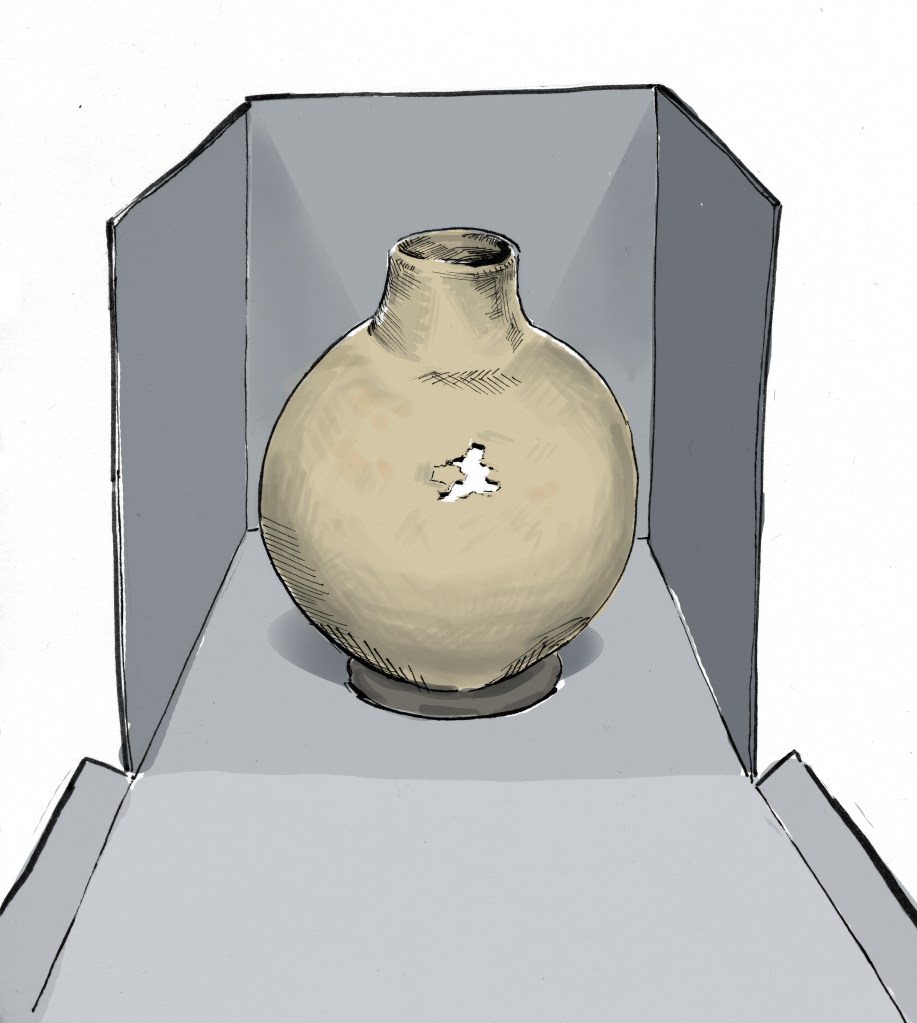

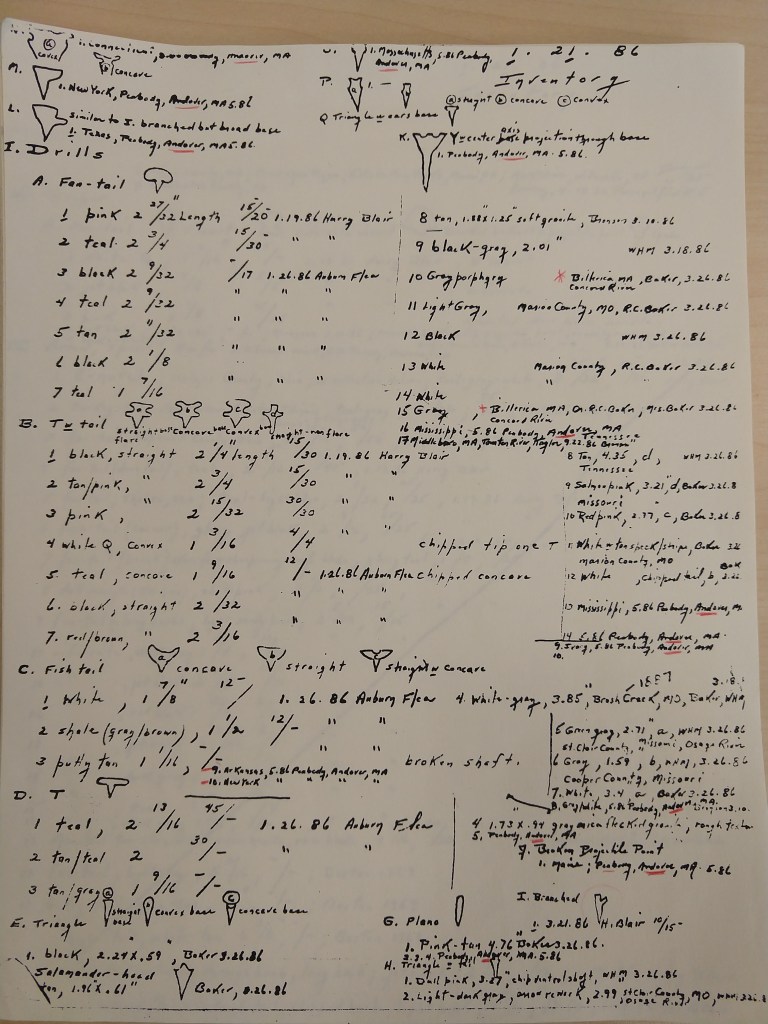

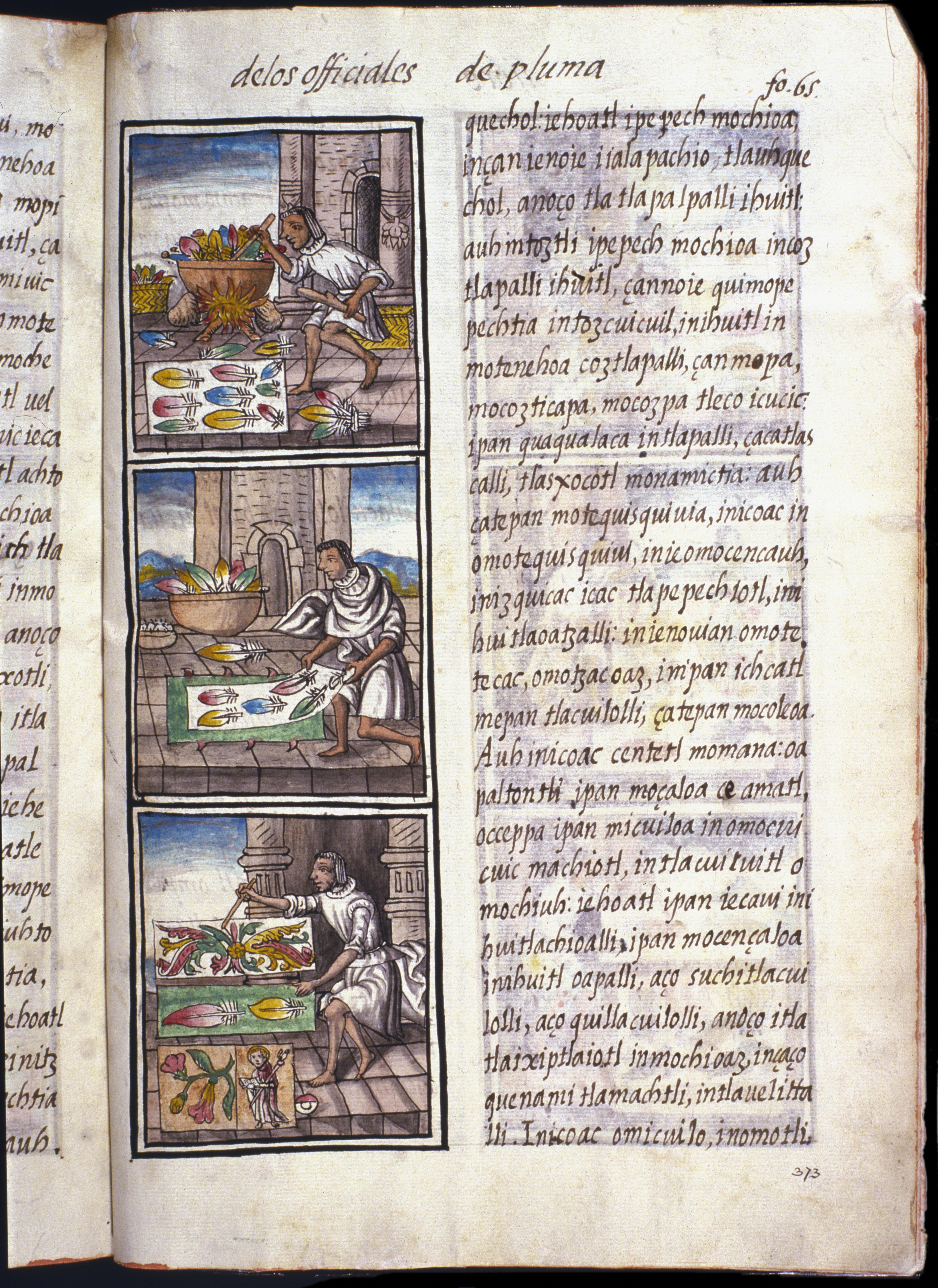

Throughout his career, Moorehead was a prolific writer, excavator, and collector. His large-scale archaeological surveys and excavations included the Arkansas River Valley, northwest Georgia, the Southwest, and coastal and interior Maine. His work directly contributed to expanding the Peabody’s collection by approximately 200,000 objects.

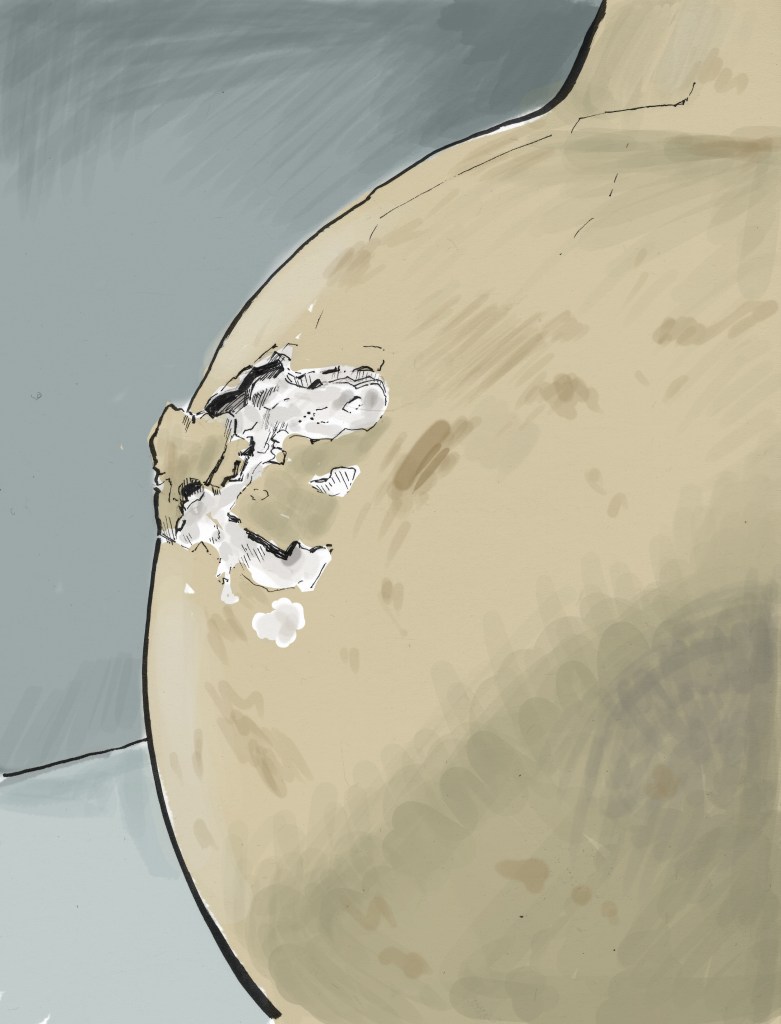

However, it must be acknowledged that Moorehead’s field and collection techniques are quite shocking by modern archaeological and museum standards. Early in his career, particularly in Ohio and Georgia, Moorehead would use horse drawn plows to cut into carefully constructed mounds. Often, his work was destructive yet superficial – he would level or bisect the mounds and collect what was of interest to him with relatively little note taking.

Moorehead was also a dealer – he regularly facilitated trades between institutions and with private collectors to fund his own work or to “remove duplicates.” Definitely something that would never be done now. And, it created lots of headaches.

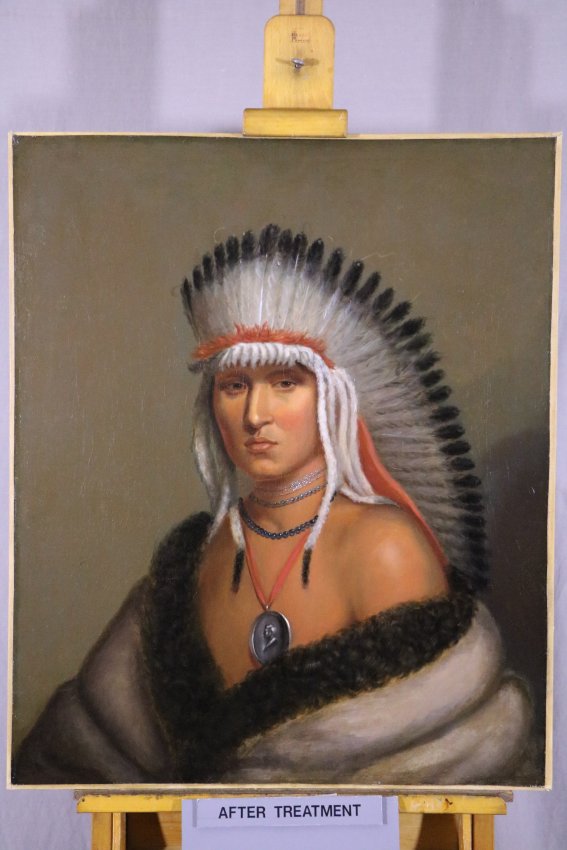

Paradoxically, Moorehead simultaneously served on the federal Board of Indian Commissioners from 1908-1933. His work there focused on injustices committed against contemporary Native Americans. He was present at Wounded Knee shortly before the infamous massacre there on December 29, 1890. He took testimony to investigate the bribery and redirection of funds in the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota. Moorehead wrote The American Indian in the United States, Period 1850-1914 to share his thoughts on the work of the Board of Indian Commissioners and expose the abuses of power that he saw.

It is perplexing to me that Moorehead was able to see the injustices done to contemporary tribes, but continue to be seemingly unaware that the material that he avidly collected and traded was connected to those same people. I firmly believe that Moorehead is an excellent candidate for a riveting biography. Anyone out there have the time to write it??