A Dialogue Between Director for Advancement Initiatives, Jennifer Pieroni, and former Peabody Institute Work Duty student and current Peabody Advisory Board member, Ben William Burke ’11.

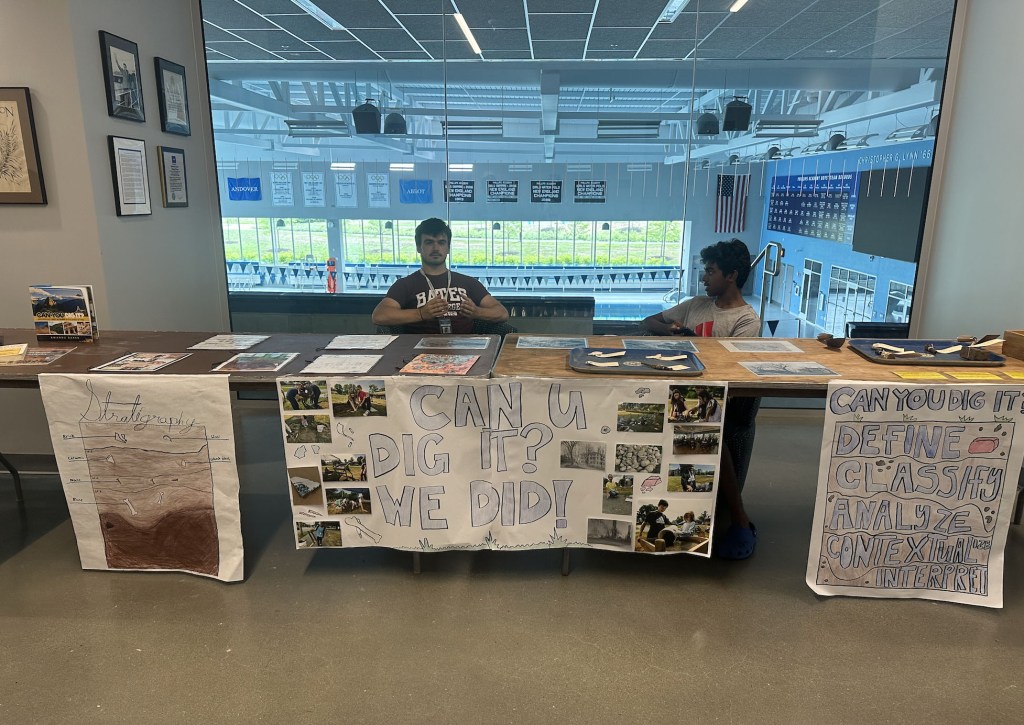

Archaeology isn’t just about uncovering and studying ancient items—at Andover, it’s about shaping a more informed, ethical, and engaged society. By learning archaeology, Andover students gain experiences to understand the world better, think critically, and contribute meaningfully to the future by better understanding the past.

At a recent Peabody Institute meeting, I met Ben William Burke ’11, whose enthusiasm for the Peabody was inspiring. As a new member of the Andover community, I wanted to understand why the Peabody had left such an indelible mark on Ben and why he continues to support it today.

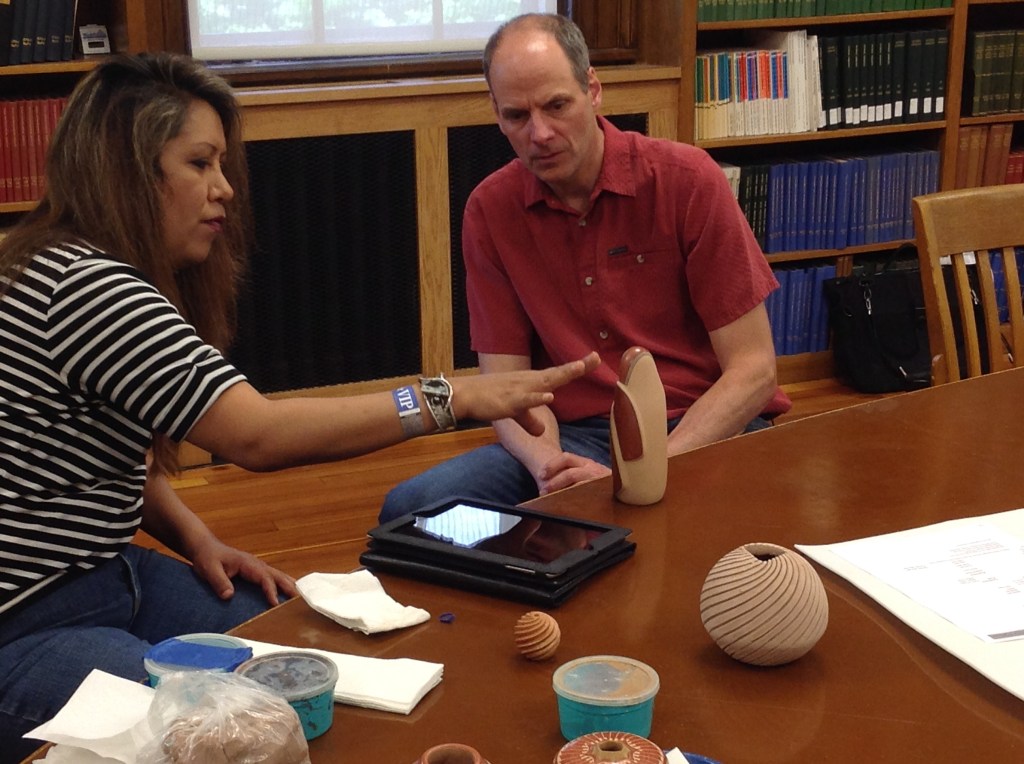

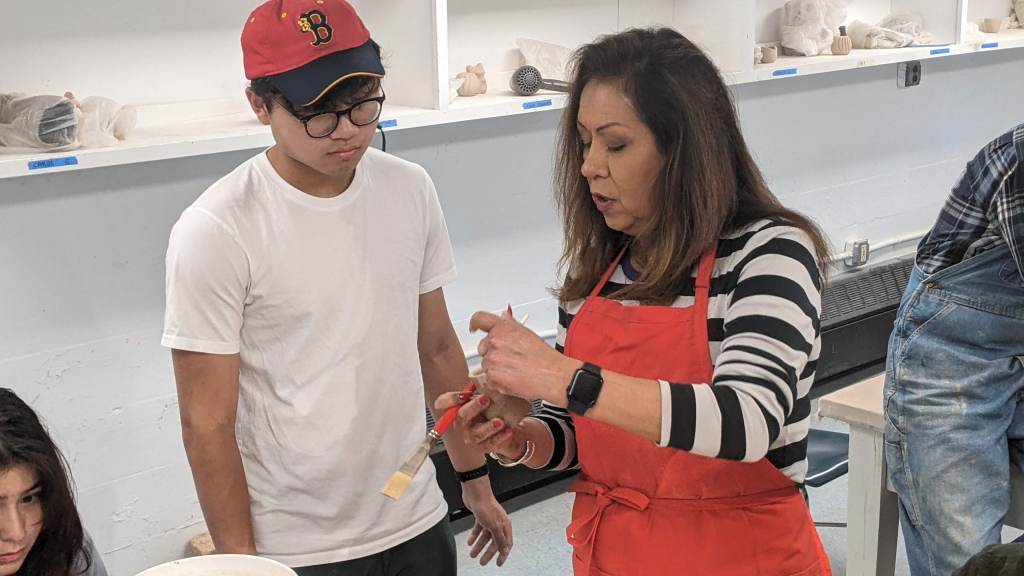

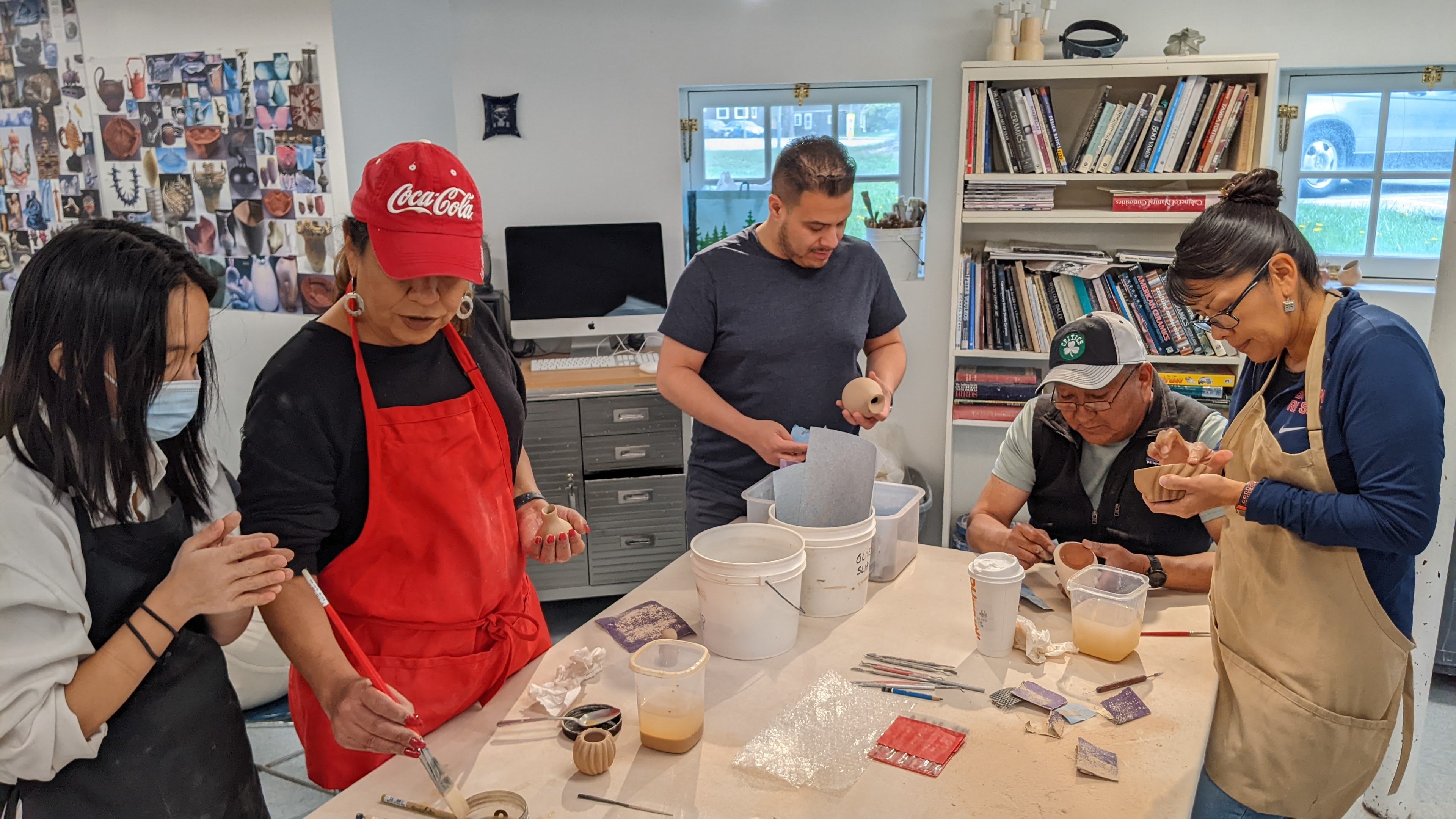

By email, Ben shared: “As a work duty student at The Peabody, I received unparalleled access to its extensive collection and cultural immersion programs. These experiences brought me face to face with — and taught me the value of — perspectives different from mine. In those moments, I was challenged to understand before correcting, to empathize before judging, and to build on the past in a way that respects it.”

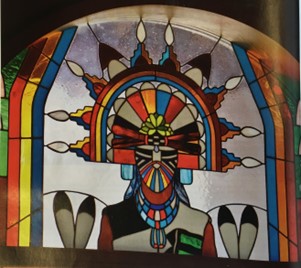

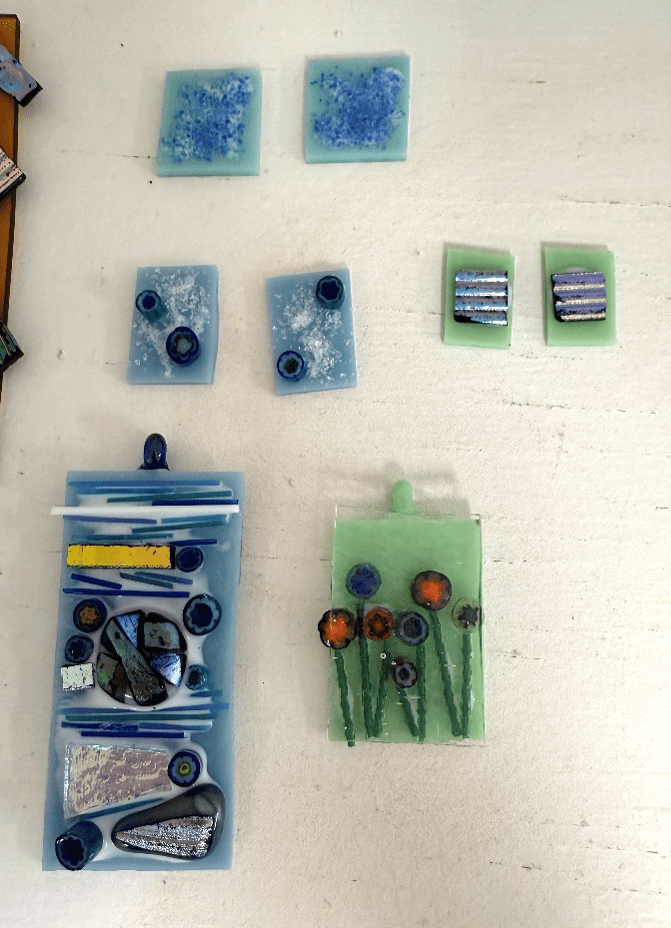

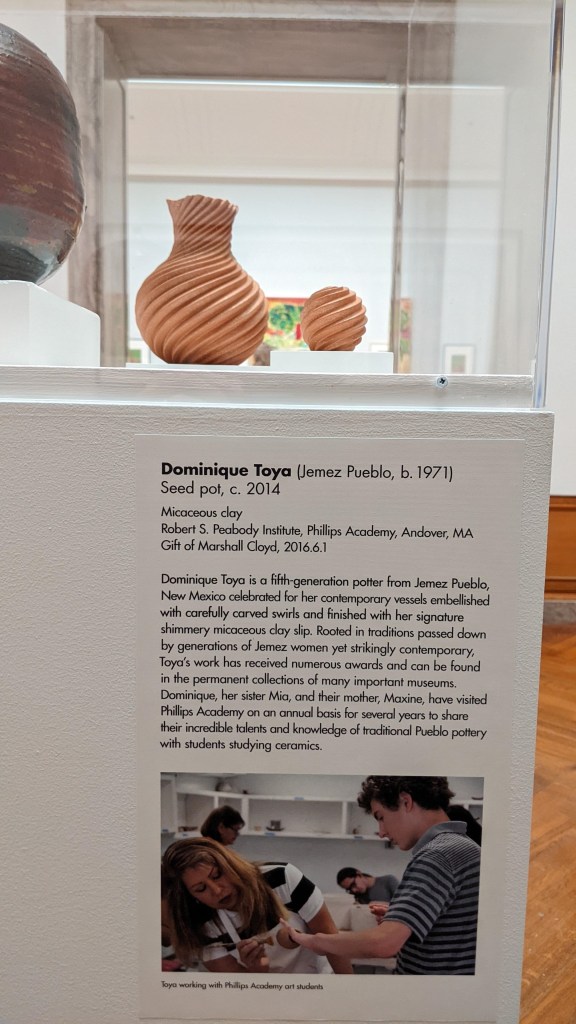

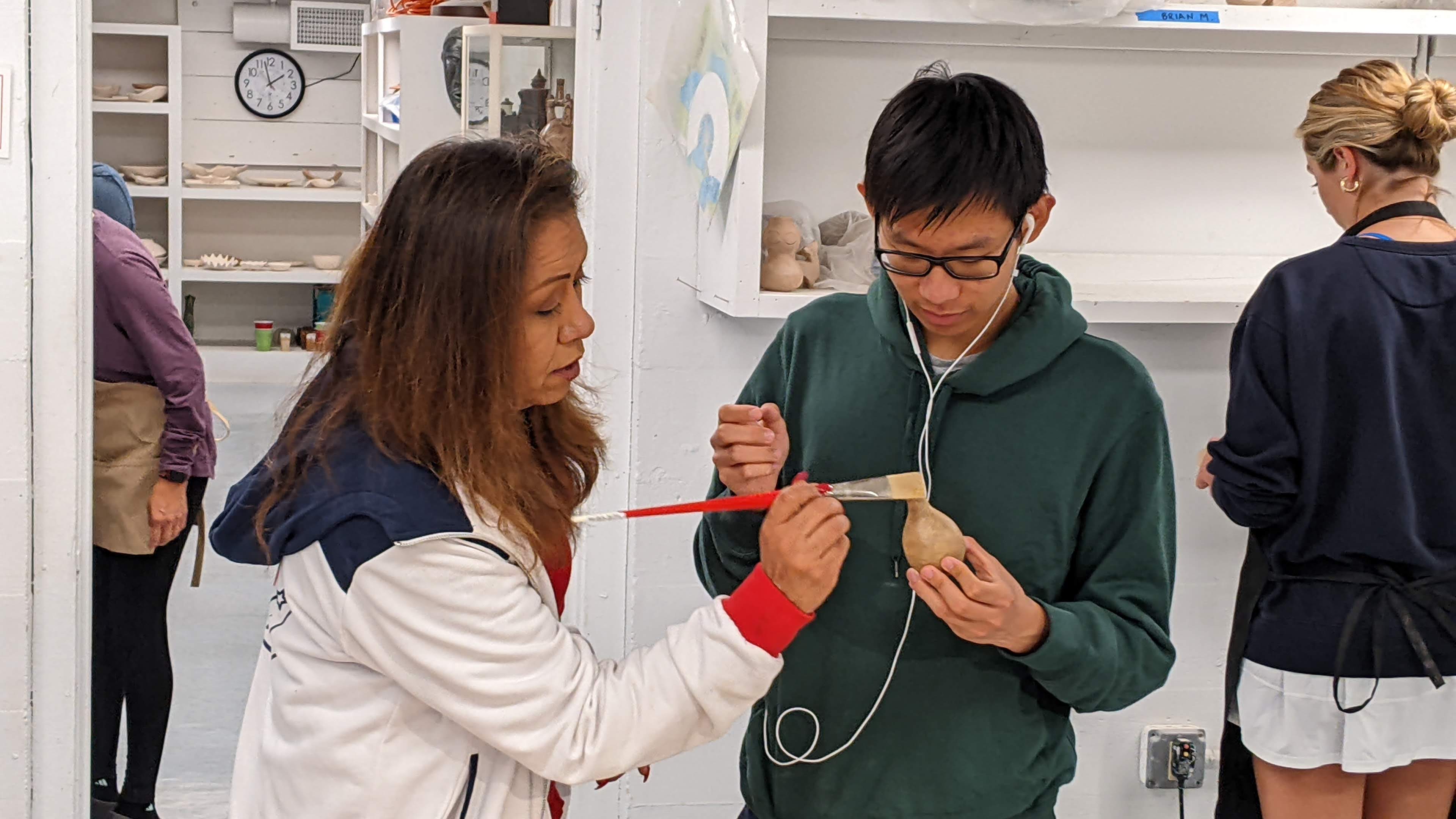

Today’s Andover students gain the transformational learning opportunity of being a part of an organization that leads in the field of repatriation and reflects Non Sibi by teaching students that archaeology is not just about personal discovery but about responsibility: to the past, to descendant communities, and future generations. Through hands-on study, students engage in meaningful, ethical work prioritizing respect over self-interest.

Ben noted, “There is not an avenue in my life that isn’t positively affected by The Peabody’s lessons in empathy and respect. I support The Peabody because I understand the value in learning to value other’s perspectives – especially when they are different from my own.”

Supporting the Peabody means investing in education that shapes responsible scholars and professionals. By supporting the Peabody with an annual gift, you can help elevate a place where teaching and learning are deeply connected to respect, collaboration, and cultural preservation. Join us in ensuring that the study of archaeology serves our Andover students and also society as a whole.