Contributed by Emma Lavoie

All work and no play makes Robert S. Peabody a dull boy!

As much as our staff and volunteers love digging deep into research and academic writings, we do love a good book or podcast! As summer descends upon us, prepare yourselves for another installment of our Peabody Picks summer list!

Book Recommendations

A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power

Genre: Historical Fiction

A Council of Dolls is a 2023 historical fiction family saga novel about multiple generations of Yanktonai Dakota women grappling with the effects of settler colonialism, told partially through the point of view of their dolls.

A modern masterpiece, A Council of Dolls is gorgeous, quietly devastating, and ultimately hopeful, shining a light on the echoing damage wrought by Indian boarding schools, and the historical massacres of Indigenous people. With stunning prose, Mona Susan Power weaves a spell of love and healing that comes alive on the page.

Wild Chocolate: Across the Americas in Search of Cacao’s Soul

by Rowan Jacobsen

Genre: Nonfiction

From James Beard Award-winner Rowan Jacobsen, the thrilling story of the farmers, activists, and chocolate makers fighting all odds to revive ancient cacao and produce the world’s finest bar.

When Rowan Jacobsen first heard of a chocolate bar made entirely from wild Bolivian cacao, he was skeptical. The waxy mass-market chocolate of his childhood had left him indifferent to it, and most experts believed wild cacao had disappeared from the rainforest centuries ago. But one dazzling bite of Cru Sauvage was all it took. Chasing chocolate down the supply chain and back through history, Jacobsen travels the rainforests of the Amazon and Central America to find the chocolate makers, activists, and indigenous leaders who are bucking the system that long ago abandoned wild and heirloom cacao in favor of high-yield, low-flavor varietals preferred by Big Chocolate.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks

Genre: Memoir, Nonfiction

Many cultural and religious traditions expect those who are grieving to step away from the world. In contemporary life, we are more often met with red tape and to-do lists. This is exactly what happened to Geraldine Brooks when her partner of more than three decades, Tony Horwitz – just sixty years old and, to her knowledge, vigorous and healthy – collapsed and died on a Washington, D. C. sidewalk on Memorial Day 2019. The demands were immediate and many. Without space to grieve, the sudden loss became a yawning gulf.

Three years later, she booked a flight to a remote island off the coast of Australia with the intention of finally giving herself the time to mourn. In a shack on a pristine, rugged coast she often went days without seeing another person. There, she pondered the varied ways those of other cultures grieve, such as the people of Australia’s First Nations, the Balinese, and the Iranian Shiites, and what rituals of her own might help to rebuild a life around the void of Tony’s death.

A spare and profoundly moving memoir that joins the classics of the genre, Memorial Days is a portrait of a larger-than-life man and a timeless love between souls that exquisitely captures the joy, agony, and mystery of life.

The Boys in the Boat by Daniel James Brown

Genre: Nonfiction

For readers of Unbroken, out of the depths of the Depression comes an irresistible story about beating the odds and finding hope in the most desperate of times—the improbable, intimate account of how nine working-class boys from the American West showed the world at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin what true grit really meant.

It was an unlikely quest from the start. With a team composed of the sons of loggers, shipyard workers, and farmers, the University of Washington’s eight-oar crew team was never expected to defeat the elite teams of the East Coast and Great Britain, yet they did, going on to shock the world by defeating the German team rowing for Adolf Hitler. The emotional heart of the tale lies with Joe Rantz, a teenager without family or prospects, who rows not only to regain his shattered self-regard but also to find a real place for himself in the world. Drawing on the boys’ own journals and vivid memories of a once-in-a-lifetime shared dream, Brown has created an unforgettable portrait of an era, a celebration of a remarkable achievement, and a chronicle of one extraordinary young man’s personal quest.

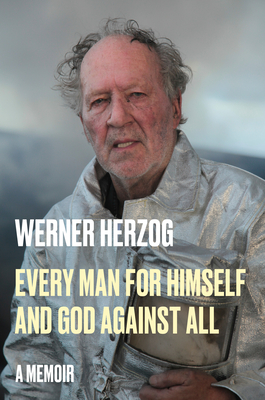

Every Man for Himself and God Against All: A Memoir

by Werner Herzog and Michael Hofmann (Translator)

Genre: Memoir, Biography

Werner Herzog was born in September 1942 in Munich, Germany, at a turning point in the Second World War. Until age 11, Herzog did not even know of the existence of cinema. His interest in films began at age 15, but since no one was willing to finance them, he worked the night shift as a welder in a steel factory. He started to travel on foot. He made his first phone call at age 17, and his first film in 1961 at age 19. The wildly productive working life that followed—spanning the seven continents and encompassing both documentary and fiction—was an adventure as grand and otherworldly as any depicted in his many classic films.

Every Man for Himself and God Against All is at once a personal record of one of the great and self-invented lives of our time, and a singular literary masterpiece that will enthrall fans old and new alike. In a hypnotic swirl of memory, Herzog untangles and relives his most important experiences and inspirations, telling his story for the first and only time.

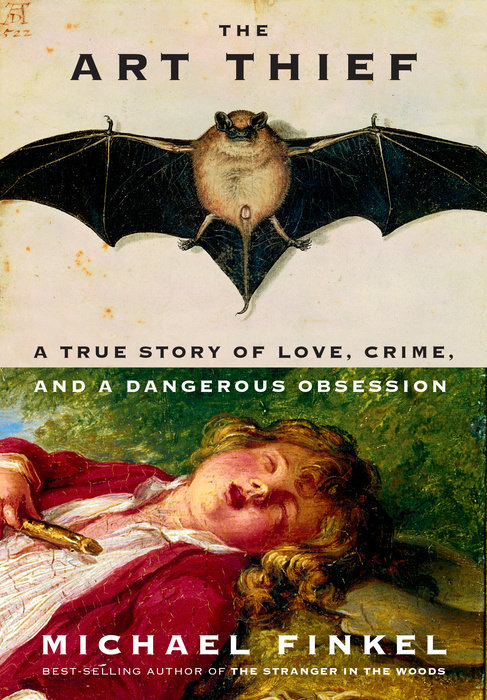

The Art Thief by Michael Finkel

Genre: Nonfiction, True Crime

One of the most remarkable true-crime narratives of the twenty-first the story of the world’s most prolific art thief, Stéphane Breitwieser.

In The Art Thief, Michael Finkel brings us into Breitwieser’s strange and fascinating world. Unlike most thieves, Breitwieser never stole for money. Instead, he displayed all his treasures in a pair of secret rooms where he could admire them to his heart’s content. Possessed of a remarkable athleticism and an innate ability to circumvent practically any security system, Breitwieser managed to pull off a breathtaking number of audacious thefts. Carrying out more than two hundred heists over nearly eight years—in museums and cathedrals all over Europe—Breitwieser, along with his girlfriend who worked as his lookout, stole more than three hundred objects, until it all fell apart in spectacular fashion.

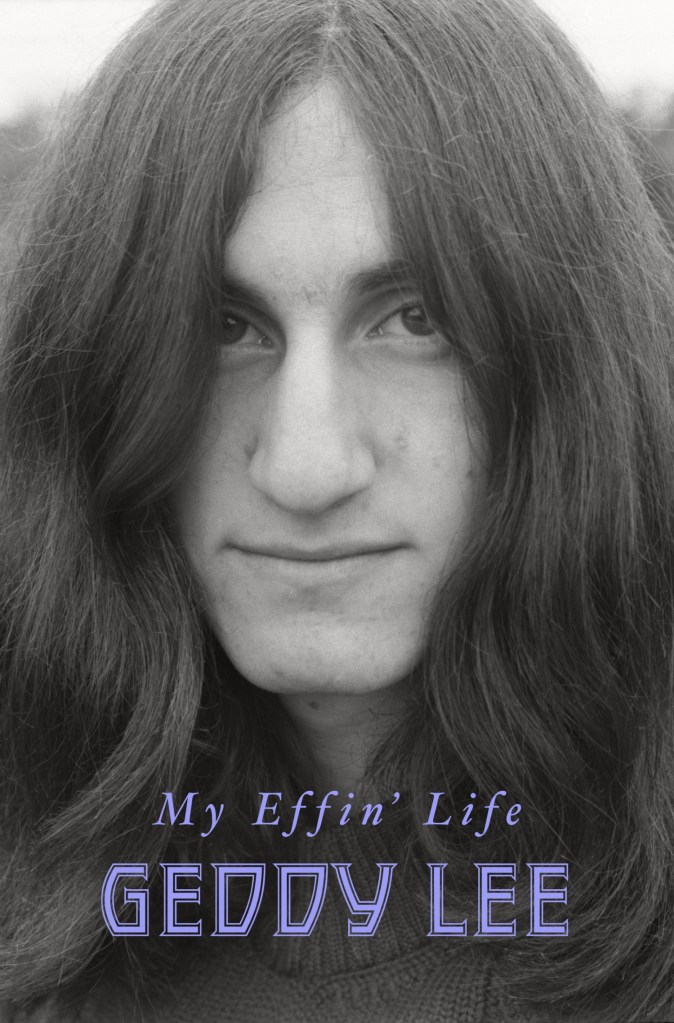

My Effin’ Life by Geddy Lee

Genre: Memoir, Biography

Geddy Lee is one of rock and roll’s most respected bassists. For nearly five decades, his playing and work as co-writer, vocalist and keyboardist has been an essential part of the success story of Canadian progressive rock trio Rush.

Long before Rush accumulated more consecutive gold and platinum records than any rock band after the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, before the seven Grammy nominations or the countless electrifying live performances across the globe, Geddy Lee was Gershon Eliezer Weinrib, after his grandfather murdered in the Holocaust. As he recounts the transformation, Lee looks back on his family, in particular his loving parents and their horrific experiences as teenagers during World War II. He talks candidly about his childhood and the pursuit of music that led him to drop out of high school. He tracks the history of Rush which, after early struggles, exploded into one of the most beloved bands of all time. He shares intimate stories of his lifelong friendships with bandmates Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart—deeply mourning Peart’s recent passing—and reveals his obsessions in music and beyond. This rich brew of honesty, humor, and loss makes for a uniquely poignant memoir.

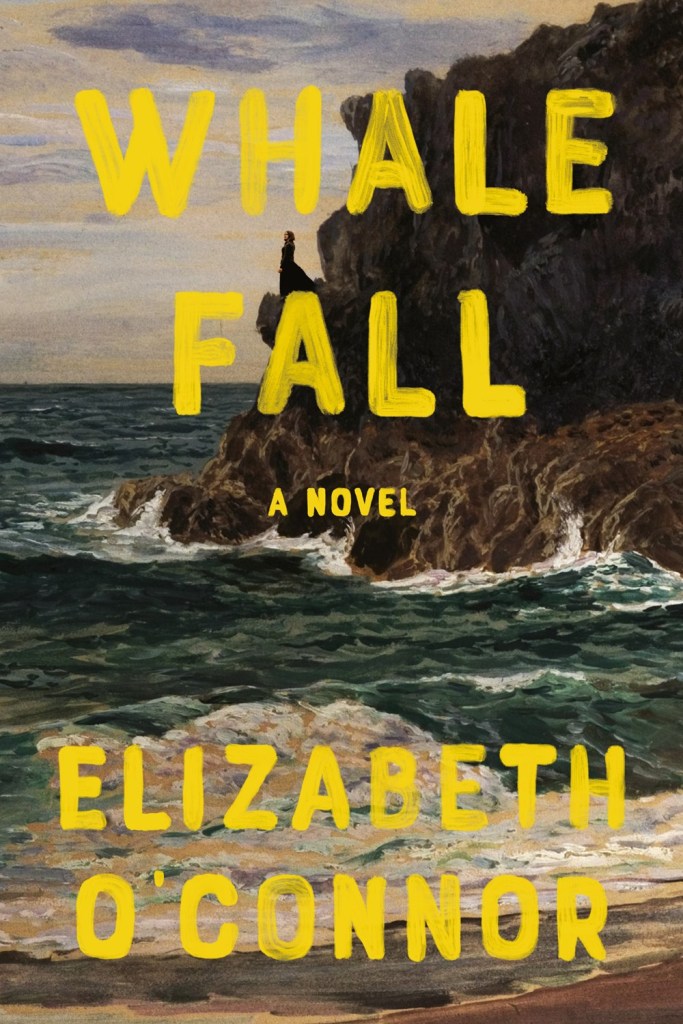

Whale Fall by Elizabeth O’Conner

Genre: Historical Fiction

In 1938, a dead whale washes up on the shores of remote Welsh island. For Manod, who has spent her whole life on the island, it feels like both a portent of doom and a symbol of what may lie beyond the island’s shores. Manod can’t shake her welling desire to explore life beyond the beautiful yet blisteringly harsh islands that her hardscrabble family has called home for generations.

The arrival of two English ethnographers who hope to study the island culture, then, feels like a boon to her—both a glimpse of life outside her community and a means of escape. The longer the ethnographers stay, the more she feels herself pulled towards them, despite her misgivings that her community is being misconstrued and exoticized.

With shimmering prose tempered by sharp wit, Whale Fall tells the story of what happens when one person’s ambitions threaten the fabric of a community, and what can happen when they are realized. O’Connor paints a portrait of a community and a woman on the precipice, forced to confront an outside world that seems to be closing in on them.

Podcast Recommendations

Our Ancestors Were Messy, Hosted by Nichole Hill (Coco Hill Productions)

Genre: History

Our Ancestors Were Messy, is a podcast covering the gossip, scandals, and pop culture that made headlines in the Black newspapers of segregated communities during the pre-Civil Rights era. On each episode, host Nichole Hill and her guests follow the story of an ancestor in search of opportunity, adventure, love, and a way to beat Jim Crow. Hill and her guests learn the mess – and eventual history – their ancestors make along the way.

“I could pretend that I like this podcast because it’s a way to learn about Black history in a way that goes beyond standard narratives of victimization or individual exceptionalism. The stories it tells allow people to be people, with all the messiness and drama and pop culture of their everyday lives in the pre-Civil Rights era. But really I love this podcast because it is just great gossip. Why you trying to make me learn in my free time??” – Lainie Schultz, Peabody Staff

The Thing About Austen, Hosted by Diane Kimneu and Zan Cammack

Genre: History

The Thing About Austen is a podcast about Jane Austen’s world — the people, objects, and culture that shape Austen’s fiction. Come for the historical context and stay for the literary shenanigans. Think of us as your somewhat cheeky tour guides to the life and times of Jane Austen.

“Two professors of literature talk about the material culture in Austen’s stories and their significance to societal culture during the Georgian and Regency eras. From Mr. Darcy’s portrait in Pride and Prejudice to the homemade alphabet in Emma and Captain Wentworth’s umbrella in Persuasion – there are so many interesting stories and histories to unpack from the items detailed in Jane Austen’s stories. Some of my favorite episodes are #83 The thing about the Ha-Ha and #52 The thing about Bath’s Baths (per their recommendation, I did try the hot spring water in the Roman Baths on a recent visit… the taste, not so great, but the experience, 5 stars!) – Emma Lavoie, Peabody Staff

Buried Bones, Hosted by Kate Winkler Dawson and Paul Holes

Genre: Historical True Crime

Buried Bones dissects some of history’s most dramatic true crime cases from centuries ago. Together, journalist Kate Winkler Dawson and retired investigator Paul Holes explore these very old cases through a 21st century lens.

“I have been a fan of Buried Bones for a few years now. Each episode is a dive into a homicide in the past that is explored simultaneously by a journalist/historian (Kate) and a retired forensic investigator (Paul). I really enjoy the blend of history and scientific analysis as the two hosts discuss the crime. Kate deftly narrates the historical event while Paul provides a reasoned analysis from a modern forensic science perspective. I always learn something!” – Marla Taylor, Peabody Staff

Salem The Podcast, Hosted by Sarah Black and Jeffrey Lilley

Genre: History

Welcome to Salem, Massachusetts! Join tour guides Jeffrey Lilley and Sarah Black as they talk all things Witch City. Learn its history, meet its people, and discover the magic.

“This podcast goes beyond the history of the Salem Witch Trials and explores the vast history of Salem and the people who live there. What does a drunk elephant, haunted pepper, a witch solving a murder, and tunnels (IYKYK) all have in common? They all relate back to Salem! This podcast has everything you need to know for your next trip to the Witch City. I personally love the episode interviews with current business owners in Salem.” – Emma, Peabody Staff