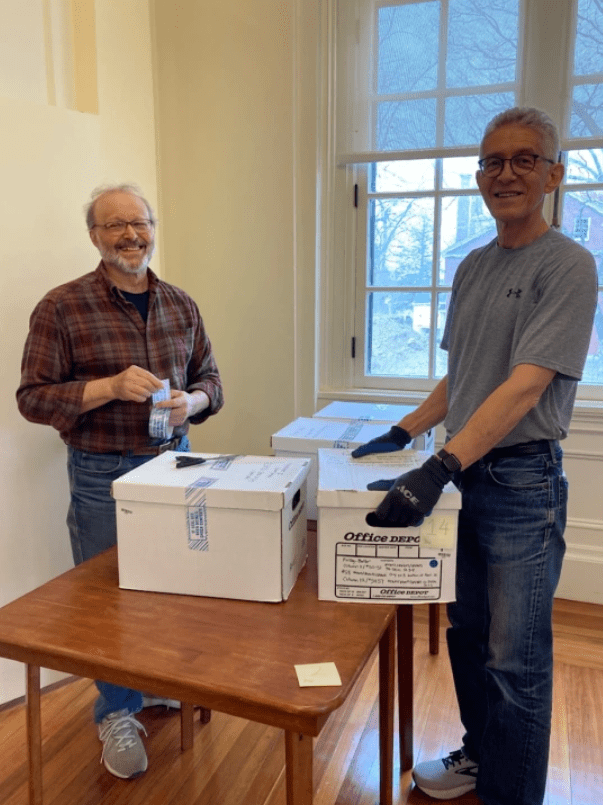

Contributed by Richard Davis

Almost five years ago, I began volunteering at the Peabody Institute. I remember speaking with Peabody Curator of Collections, Marla Taylor, one evening after an evening presentation there and, as they say, the rest is history. In my time there, I think I’ve seen every possible iteration of projectile point imaginable – and there have been many – but what resonates most for me are the stories behind almost every object I’ve handled.

The museum has an important collection of approximately 600,000 objects essentially from North, Central, and South America. It is unlikely that I’ll get to see or work with every one. So far, I have helped catalog 12,000 year old bones from a cave in Peru where South American agriculture is believed to have started, reshelved a couple of dozen hominid skull casts, been taught the rudiments of differentiating mere stones from artifacts that were used for a myriad of tasks, and more.

How I ended up there is a longer story, but on one of several tours, a tomahawk that was found after the Battle of Little Big Horn was shown to me. It was made from a table leg and a piece of metal from another object that was pounded into its newer, more lethal form. My son thought that was pretty compelling and asked for a photo of me with that object – the museum and I willingly complied.

I recently was examining an object that I couldn’t identify – as with many things my neophyte status should suggest – and I asked my ‘boss’ what it might be. You need to understand that the folks at the museum have seen and handled many such objects, so when they get excited by one, I figure it has some particular traction. Marla said – “Oh – that’s really cool,” so I paid close attention.

She said that it was made of flint – it was both very fine grained and smooth, except for some obvious flakes that had seemed to have been worked by somebody – something. Further, she said she knew that it came from a particular region in France and proceeded to pull up a Google search that clearly matched the object I held – a stone hand axe. So far, so good.

Next to the photo and a map were the characters ‘1MYA’ – which, I had to ask about. They, of course, meant 1 Million Years Ago. So – in my hand, I held a hand axe from France that was picked up, engineered, and used by somebody, something about one million years ago!

I went home and found myself puzzling over the object and its age. I can’t keep straight Homo sapiens, Australopithecus, Neanderthal, or any of those beings and ages, but I felt pretty sure that Homo sapiens didn’t go back that far. And after e-mailing Marla the next day, I was assured that indeed, it wasn’t of Homo sapiens origin – it was Home erectus – dating back to that 1MYA descriptor.

So – in short, I’ve had the privilege – for it is that – of holding an object, made by an ancient being for whatever purpose he or she felt necessary. I’m assuming that they weren’t thinking that it would be cool if it ended up in museum someday. They were using it to be sure they ate that night and survived long enough, so that we H. sapiens would have a go in their future.

So – long story short – it’s pretty much not only educational and worthwhile, but lots of fun volunteering at the Peabody.

After five years, I continue to enjoy and feel productive with my time at the Peabody – enmeshed with interesting objects with compelling stories, but more importantly with an amazing group of staff, colleagues, and friends. To a one, they are intelligent, patient (no job need be done in haste or unsafely), generous in both time and knowledge, and tolerant of my quirky humor and often bad puns. It doesn’t get any better.