Contributed by Ryan Wheeler

We were fortunate to receive a generous gift from Phillips Academy trustee and Peabody Advisory Committee member Peter T. Hetzler MD, FACS (Class of 1972) in December 2017 that allowed us to purchase several important books to add to our library.

One of these is the very rare, privately published volume Birdstones of the North American Indian by Earl C. Townsend, Jr. Published in 1959, Townsend’s book was limited to 700 copies. A reprint edition was released in 2003 by Steven Hart, but these are also scarce and hard to find. Both the original edition and the reprint can be quite expensive, if you are lucky enough to find one. Townsend (1914-2007) was an attorney and founding member of the Indiana Archaeological Society, as well as an avid collector of Native American artifacts, cars, and artwork. According to Townsend’s obituary, he was honored by the Black River-Swan Creek Saginaw Chippewa Tribe with the name Senee Pen Eshee Na Na, meaning “Birdstone Man.”

Townsend’s preface begins with a reference to Warren Moorehead, the Peabody’s first curator, who “spoke of the need for specialized volumes, each devoted to one particular form of prehistoric North American Indian relic.” Moorehead insisted that the province of archaeologists was the study of material culture and he urged his contemporaries to abandoned reconnaissance and site survey that were becoming more common in the first quarter of the twentieth century and hunker down on description and classification of artifacts. Moorehead published at least three volumes that highlighted objects, mostly those held by artifact collectors. His most expansive was the 1910 two volume The Stone Age in North America. Moorehead also published more detailed studies of particular artifact types, like his 1906 The So-Called “Gorgets,” an early bulletin of the Phillips Academy Department of Archaeology, and his 1899 The Bird-stone Ceremonial.

Townsend’s 719-page book is nothing short of monumental, and depicts thousands of birdstones from public and private collections. He also covers the ideas about what these objects are, which are myriad and diverse, as well as how they were made, distribution patterns, cultural affiliations, and fraudulent specimens.

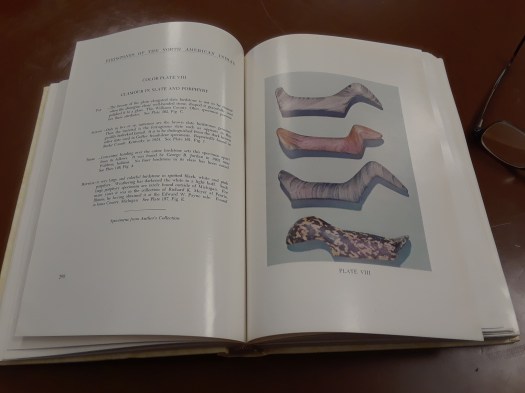

So, what is a birdstone? As Townsend notes, this is not an easy question to answer, since there is no clear agreement on how they were used in antiquity. In terms of form, birdstones are often described as highly stylized depictions of birds. A variety of distinct forms are all described in detail by Townsend. The virtuosity of manufacture, incredible symmetry, and sculptural quality have often elicited comparison with modern art. Sizes range from an inch or two to larger examples that are five or six inches in length. A common feature is the presence of bi-conically drilled holes, one at either end of the birdstone’s base. These holes are often the site of breakage and repair. Most birdstones are made of banded slate, especially the greenish-gray banded Huronian variety, but other stones were used as well, including porphyry. Many have projecting eyes or ears. Few if any have come from secure archaeological contexts and most are known as field finds. Townsend’s distribution map indicates that the vast majority of birdstones in his sample come from areas around the southern margins of the Great Lakes, especially in Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, New York, and Ontario. Cultural affiliations of birdstones vary across this area and include a number of Late Archaic and Early Woodland cultures like Glacial Kame and Red Ochre, circa 1500-500 BCE.

Townsend does a nice job of summarizing the diverse opinions on birdstones. The ideas range from Charles C. Abbott’s notion that they were worn as hair ornaments by women during maternity to use as a spear thrower (atlatl) counterweight. Other ideas include attachment to flutes or similar musical instruments, game pieces, hair or clothing ornaments, staff mounted religious symbols, and atlatl handle grips (Townsend’s preferred idea). Considering the diversity of forms, it seems likely that different styles were used in different ways and there are probably layers of meaning that we are unable to detect. Many contemporary archaeologists have accepted that birdstones are, in fact, associated with atlatls or spear throwers (for example, this is how they are described by David Penney in his essay on Archaic art in the 1985 exhibit catalog Ancient Art of the American Woodland Indians). Many articles about birdstones have been added to the literature since the 1959 publication of Townsend’s book, often proposing new ideas or offering further support or evidence for an existing hypothesis.

We were particularly excited to acquire a copy of Townsend’s Birdstones because the Peabody collections contain many examples of this enigmatic and interesting artifact. Only a few, however, are illustrated in Townsend’s book, including two from Ohio that had been salvaged after breakage (see Townsend 1959: Plates 76s and 77h). A few other fine examples from the Peabody are illustrated here.

It’s unlikely that we will unlock the secret of the birdstone anytime soon, however, we are immensely grateful to Peter Hetzler for his generous gift of the Earl Townsend book, which nicely complements our object collection!

University of Connecticut PhD candidate Zac Singer was the first recipient of the Linda S. Cordell Memorial Research Award, which supported his reanalysis of the Neponset site collection, specifically focusing on the middle Paleoindian (circa 10,000 to 11,000 years ago) assemblage from the site. Singer will use the data to complement his excavation and analysis of a Paleoindian site on the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation in southeastern Connecticut. This research will expand understanding of Paleoindian life in the Northeast, including study of lithic sources and stone tool manufacture; the work also will document a significant but little-studied Peabody Museum collection.

University of Connecticut PhD candidate Zac Singer was the first recipient of the Linda S. Cordell Memorial Research Award, which supported his reanalysis of the Neponset site collection, specifically focusing on the middle Paleoindian (circa 10,000 to 11,000 years ago) assemblage from the site. Singer will use the data to complement his excavation and analysis of a Paleoindian site on the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation in southeastern Connecticut. This research will expand understanding of Paleoindian life in the Northeast, including study of lithic sources and stone tool manufacture; the work also will document a significant but little-studied Peabody Museum collection. Jessica Watson is a PhD candidate at University at Albany-SUNY. Her research involves analysis of animal bones from the Frisby-Butler and Hornblower II sites on Martha’s Vineyard. These collections were donated to the Peabody in 2012 by Jim Richardson and represent excavations made in 1982 with the late archaeologist Jim Peterson. Jessica says her dissertation research will use “faunal assemblages from sites in the Northeastern U.S. … (to) examine human-environmental interactions by identifying changes in animal populations during early European colonization (ca. 1600-1700).” Her dissertation is tentatively titled Ecological Effects of Colonization on Mammals and Birds along the Northeastern Atlantic Coast.

Jessica Watson is a PhD candidate at University at Albany-SUNY. Her research involves analysis of animal bones from the Frisby-Butler and Hornblower II sites on Martha’s Vineyard. These collections were donated to the Peabody in 2012 by Jim Richardson and represent excavations made in 1982 with the late archaeologist Jim Peterson. Jessica says her dissertation research will use “faunal assemblages from sites in the Northeastern U.S. … (to) examine human-environmental interactions by identifying changes in animal populations during early European colonization (ca. 1600-1700).” Her dissertation is tentatively titled Ecological Effects of Colonization on Mammals and Birds along the Northeastern Atlantic Coast. Adam King is Research Associate Professor at the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina. His Cordell project focuses on Warren Moorehead’s 1925-1927 excavations at the Etowah site village near Cartersville, Georgia. King says, “my goal is to use the artifacts and documents produced to help evaluate the … ideas about the distribution of village areas at the site and the possibility that the Late Wilbanks village was burned.” He plans to examine pottery collections from the site and collect carbon samples for radiocarbon dating. Adam’s dissertation on the Etowah site was published as Etowah: The Political History of a Chiefdom Capital (2003) and his research was instrumental in NAGPRA determinations of affiliation made by the Peabody in the 1990s.

Adam King is Research Associate Professor at the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina. His Cordell project focuses on Warren Moorehead’s 1925-1927 excavations at the Etowah site village near Cartersville, Georgia. King says, “my goal is to use the artifacts and documents produced to help evaluate the … ideas about the distribution of village areas at the site and the possibility that the Late Wilbanks village was burned.” He plans to examine pottery collections from the site and collect carbon samples for radiocarbon dating. Adam’s dissertation on the Etowah site was published as Etowah: The Political History of a Chiefdom Capital (2003) and his research was instrumental in NAGPRA determinations of affiliation made by the Peabody in the 1990s. ersity where he teaches courses on human rights and ethics, cultural property, the archaeology of North America, and the peopling of the Americas. He received the Linda S. Cordell Memorial Research Award to support his ongoing documentation of Paleoindian and Early Archaic period artifacts. Dave has already collected over 5000 early stone tool images, mainly from the Southeast, and new data from the Peabody’s collections will be used in several shape analyses, particularly looking at shape differences and assessing the degree of regional variation. He notes that current shape analyses of Paleoindian tools has been done on small datasets and that his “intent is to analyze hundreds of Paleoindian and Early Archaic artifacts to produce robust statistical inferences about temporal and spatial group relationships.” Dave received his PhD in 2006 from Florida State University in Tallahassee and serves as president of the non-profit

ersity where he teaches courses on human rights and ethics, cultural property, the archaeology of North America, and the peopling of the Americas. He received the Linda S. Cordell Memorial Research Award to support his ongoing documentation of Paleoindian and Early Archaic period artifacts. Dave has already collected over 5000 early stone tool images, mainly from the Southeast, and new data from the Peabody’s collections will be used in several shape analyses, particularly looking at shape differences and assessing the degree of regional variation. He notes that current shape analyses of Paleoindian tools has been done on small datasets and that his “intent is to analyze hundreds of Paleoindian and Early Archaic artifacts to produce robust statistical inferences about temporal and spatial group relationships.” Dave received his PhD in 2006 from Florida State University in Tallahassee and serves as president of the non-profit