Contributed by Adam Way

This blog is the culmination of work done by Independent Researcher/Volunteer Adam Way to explore how the Peabody Institute has been portrayed by Phillips Academy students in The Phillipian over the years. Adam shared two previous blog posts about his work (Combing Through the Phillipian and Combing Through The Phillipian: End of an Era) and recently completed the project. His final blog is a summary of what he learned.

The relationship between The Phillipian and the Peabody Institute has existed since the Institute’s founding back in 1901, and while the strength of that relationship has waxed and waned, it has persisted nonetheless. During my time combing through over a century’s worth of The Phillipian issues, I have noticed a few substantial changes, mainly the amount of coverage that the Peabody Institute received, the type of coverage, and the student’s view of Peabody.

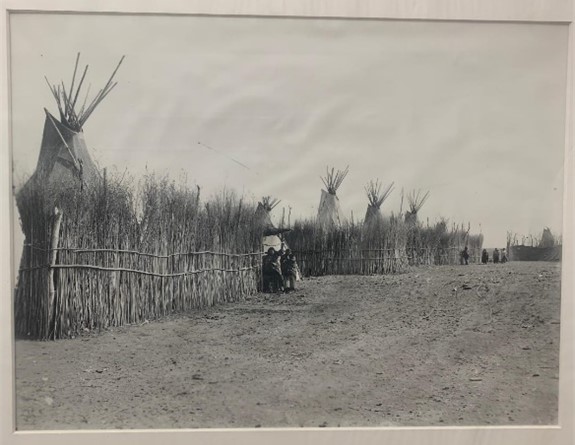

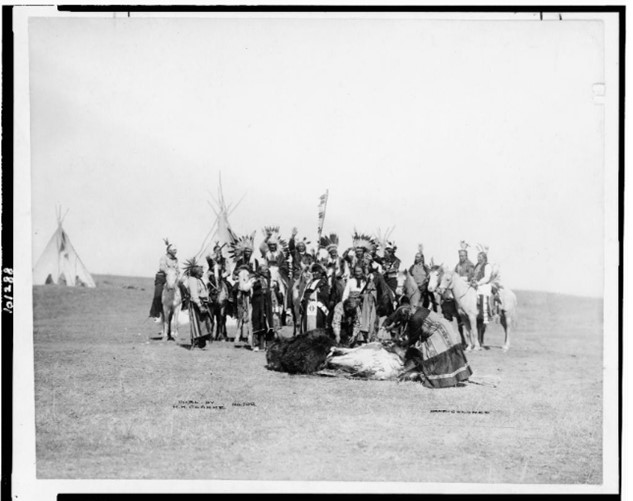

The first major difference that appears when looking through The Phillipian archives is that the number of times that the Peabody is addressed/mentioned decreases drastically towards the present. In 1910, the Peabody Institute, then the Department of Archaeology, was mentioned 153 times throughout the year, with the following years yielding similar results. A significant amount of the times that the Peabody Institute was mentioned in these early years can be attributed to the existence of extracurriculars that took place within the building. Events such as meetings of the Banjo or Drama clubs and other such student activities that took place in the Peabody make up a large portion of mentions, while the rest is composed of articles detailing the academic work and scholarship being conducted by the Institute.

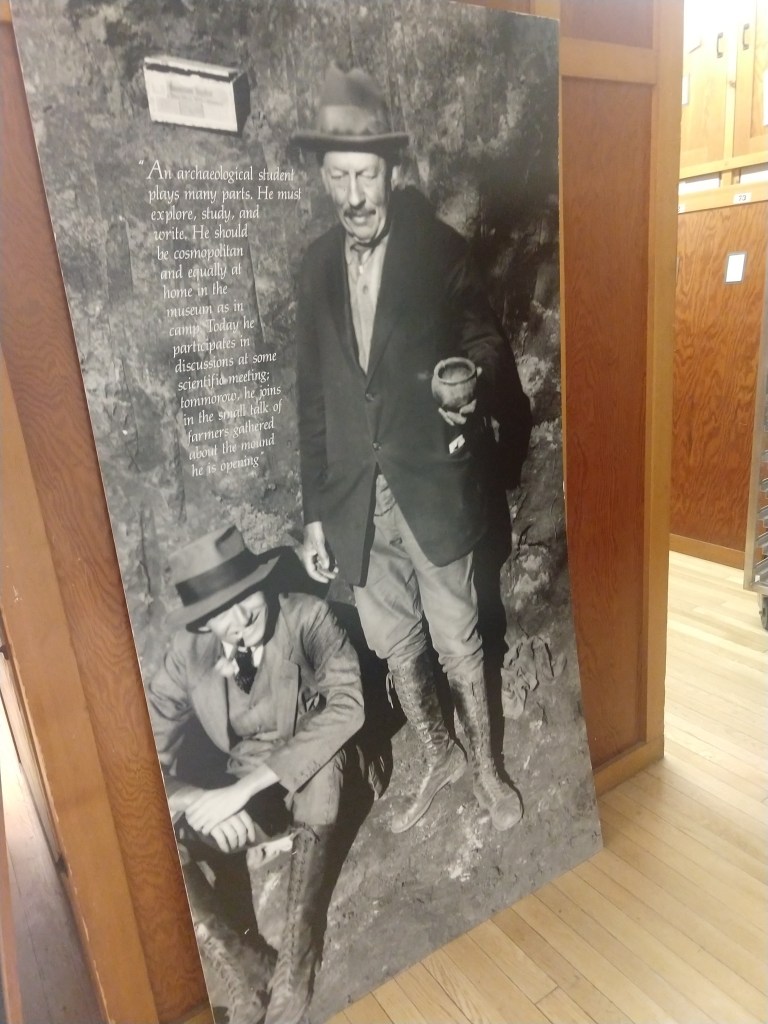

The constant high volume of mentions during the early years of the Peabody Institute, unfortunately, do not last forever. It appears that the turning point was, more or less, when Warren K. Moorehead retired from his position as director and was replaced by Douglas Byers. While the overall number of yearly mentions had been on a steady decline since the beginning of the century, the number had remained relatively consistent and the articles were primarily focused on academic work and lectures at the Peabody Institute. This changed when Byers and curator Fred Johnson took over, as it appears that these two did not have as close of a relationship with the The Phillipian as Moorehead did. This trend continued, and arguably was exacerbated under Richard “Scotty” MacNeish. I believe that this divide can be attributed to a shift in focus from teaching in the classroom to fieldwork, as all three of these former directors placed a heavy emphasis on fieldwork, while there was a lack of a consistent archaeology and/or anthropology class during this period (with other factors playing into that decision like student interest). Luckily, in the time since MacNeish, the Peabody Institute has regained a stronger, and more frequent, presence in the The Phillipian.

The next major change that I noticed while conducting this research, was that the type of coverage that the Peabody received changed over the years. Initially, I noticed this change through the club announcements. As time went on, the number of clubs using the Peabody, or at least publishing that they were in The Phillipian, was declining. Nothing about this appeared to be out of the ordinary as clubs moved to other buildings and Peabody House was constructed for the purpose of holding social events and clubs. The part that seemed strange to me was when members of the Peabody staff and faculty would leave without a single mention of their departure and only a brief mention when their replacement had been found, as was the case with Dick Drennan in 1977. However, as time progressed, the type of coverage in this area also shifted. Not only was there an article detailing the departure of the previous director, Malinda Stafford Blustain, but there was a subsequent article about the hiring of her replacement, Ryan Wheeler. It appears that the relationship between the The Phillipian and the Peabody Institute is steadily returning to its former strength.

The last major change that I have noticed is the waxing and waning of student interest in the Peabody Institute over the years. As with the other two variables that changed over time, student interest seemed to peek early on before dropping drastically as time progressed. After Moorehead’s departure and the subsequent drop in attention received from The Phillipian, the Peabody became increasingly referred to as a “hidden gem” and “unused asset.” There were even pieces written as a joke that say a student died of boredom due to their visit to the Peabody. Pieces like these are written in good fun, however, it does highlight the disparity between how involved students once were and how involved they are now. As with the other two changes that I noticed, this too is changing for the better in recent years. While there are still joke articles, there are fewer instances where the Peabody is labeled as an “unused asset.” There appears to have been a positive reception of student travel programs in the recent past as well as current lectures and other programs offered by the Peabody Institute.

While my time combing through The Phillipian has come to a close, I am glad to see that the Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology is making a resurgence within the paper. The records showed that the institution has been through some difficult times and yet has prevailed and is strengthening its place within the Academy and student life.