Contributed by Ryan Wheeler

A quick Google search reveals that Ruth Benedict still looms large in the minds of contemporary anthropologists. Benedict (1887-1948) is known for many things—she was a favorite student of anthropology icon Franz Boas, she conducted multidisciplinary work across anthropology, psychology, and social science, and was close friend and confidant of Margaret Mead. Mead wrote a marvelous biography of her friend that gives her impressions alongside published and unpublished works by Benedict. Biographies continue to appear, including two dual bios of Mead and Benedict. Benedict wrote and talked about the paradigm shift in our field that she witnessed in the twentieth century as Boasian humanism gave way to scientific approaches. She famously argued that anthropology needed both.

Benedict has fared pretty well in the internet age. Blogger Jason Antrosio, writing at Living Anthropologically, pits Benedict against social geographer Jared Diamond, arguing that Benedict did what Diamond does, only better, more eloquently, with at least as much erudition, more personally, and at least seventy-five years before Diamond. Antrosio’s satiric comparison specifically looks at Diamond and Benedict’s take on what traditional societies have to teach the Western world. Likewise, Alex Golub, in his blog Savage Minds, argues that Benedict’s concise prose presages today’s best blog writing. Perhaps not surprisingly, some of Benedict’s more pithy insights appear on internet sites dedicated to quotation. One of these quotes has gotten a lot of attention recently—here it is:

“The purpose of anthropology is to make the world safe for human differences”

Along with a presence on the quotation websites, this quote has made the rounds as an internet meme (framed against a nice photo of Benedict) and, perhaps most famously, was featured in remarks made by President Barack Obama during a press conference with Afghan President Ghani on March 24, 2015. The President referred to his own mother’s training as an anthropologist, as well as Ghani’s background. The remark, however, doesn’t specifically attribute the quote to Benedict. Simon Kuper, writing in The Financial Times, has dubbed Barack Obama the “anthropologist-in-chief” and a number of others have pointed out that President Obama’s interest in anthropology has tracked a growing interest in our discipline.

Specifically too, that quotation has resonated with a lot of people, myself included. I added it to my e-mail signature sometime over the summer—a place that I usually reserve for my contact info alone. I did notice, however, that while the quote appeared on a lot of websites, there was never any specific source cited. Archaeologist Meg Conkey told me recently that she too like the quote, but was unsure of its origins. She asked me if I knew and pointed out a Reddit post about the quote. The Reddit post argues that “Ruth Benedict never said it, not in any of her published writings. It seems to be merely myth. It is never specifically cited, nor does it make historical sense. In her own time, anthropology was a SCIENCE, not a political party.” The post includes a long list of internet memes, blog posts, and other websites that all attributed the quote to Benedict, but with no specific reference to back it up.

The quote aside for a moment, it is pretty clear that Benedict’s work had a strong political element. In many ways, as a cultural relativist, she sought to challenge American exceptionalism with her work. Benedict, along with anthropologist Gene Weltfish, prepared a pamphlet titled “The Races of Mankind” in 1943, intended as a guide for American troops operating overseas. This became an appendix to later editions of her 1940 book Race: Science and Politics, which makes both a humanistic and scientific case for the equality of all races.

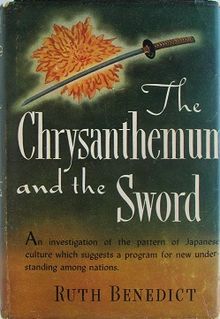

During WWII Benedict prepared an “ethnography at a distance” study of Japanese culture for the U.S. Office of War Information, which appeared in 1946 as The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture. Along with her earlier work, Patterns of Culture, Chrysanthemum remains one of Benedict’s iconic projects. And it may provide a clue about that quote. This is what Benedict writes on page 14 of Chrysanthemum:

“The tough-minded are content that differences should exist. They respect differences. Their goal is a world made safe for differences, where the United States may be American to the hilt without threatening the peace of the world, and France may be France, and Japan may be Japan on the same conditions.”

Anthropologists certainly are a tough-minded lot, even if we get a bit loosey-goosey on our quotations. I suppose this is a consequence of progress, as brainyquotes.com replaces Bartlett’s.

A trip to the bookshelf provides another clue. On page 402 of their textbook Anthropology: The Human Challenge (15th edition) William Haviland and his co-authors include a nice profile of Ruth Benedict. There they say:

As Benedict herself once said, the main purpose of anthropology is “to make the world safe for human differences.”

So, she did say this, or at least something a lot like this. For the precise, we should likely reconsider using those quotes or their exact placement. It’s not surprising, however, that we still have a special place for Benedict in our discipline. Blogger Antrosio makes a nice point that Benedict, however, isn’t perfect, and that she suffers from the same flaws that afflict Jared Diamond:

“This history reveals the major theme missing from both Benedict and Diamond–an anthropology of interconnection. That as Eric Wolf described in Europe and the People Without History. Peoples once called primitive–now perhaps more politely termed tribal or traditional–were part of a co-production with Western colonialism.”

Johannes Fabian, in his 1983 book Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object, makes much the same argument. Despite the shortcomings, Benedict has a lot to offer, from ideas about cultural relativism and race, to the direction that anthropology can take in the twenty-first century. As the contemporary scientific paradigm breaks free of its dialectic with humanism, can humanism assert itself in whatever comes next?

Dr. Wheeler, thank you for tracking down the origin of the distorted quote. I expected that the quote originated as a COMPLETE invention, but I was wrong. To be fair, the way Ruth Benedict actually expressed it is more forgivable: making the world safe for human differences is one of the goals of the social scientists whom she idealizes. She did NOT express such activism as “the purpose of anthropology,” a modern opinion I find much less forgivable. There must be only one purpose of any field of science: truth. Or else such a field is not science.

LikeLike

Thanks for your note–apparently twisted and incorrectly attributed quotes have become quite common–see Garson O’Toole’s new book http://www.opb.org/artsandlife/article/npr-hemingway-didnt-say-that-and-neither-did-twain-or-kafka/

LikeLike

Thank you for writing this and tracking down these quotes. And thank you for the link to my site. I have always felt that the “purpose of anthropology” quote is more of an encapsulation of her last paragraph of Patterns of Culture. You are correct that it shows up more closely in Chrysanthemum, but there it takes on a strange almost nationalist hue.

One tiny quibble: I have an “n” in my last name. Antrosio. Thanks!

LikeLike

Jason–many thanks for your comment! Please accept my apologies for misspelling your name! I’ve fixed that.

LikeLike

Thanks so much, appreciate the sleuthing you’ve done!

LikeLike

And, from the new book Gods of the Upper Air, “He believed the world must be made safe for differences,” Ruth Benedict wrote when Boas died. This seems like a quote that hews even closer to the oft-quoted quote, if Boas is a stand in for anthropology writ large. See: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/08/26/how-cultural-anthropologists-redefined-humanity

LikeLike

Chip– thank you very much for this source. (And Ryan, thank you for this post.) Just for the sake of detail, the original article seems to be Ruth Benedict, “Franz Boas,” THE NATION, January 2, 1943, p. 15 — and, as you point out, it’s cited in Charles King’s GODS OF THE UPPER AIR

LikeLike

This post is very good, thanks for posting!

LikeLike