Contributed by Alberto Agudo (’25)

I stumbled upon the Pecos bone flutes on a bright September afternoon that was supposed to be about beaver pelts and fur trade ledgers. My history class had followed Ms. Doheny to the Robert S. Peabody Institute for a lecture, but after the talk I lingered and asked the speaker, Dr. Lainie Schultz, whether the museum kept any musical instruments. That single question carried me into the archives, where Curator Marla Taylor opened a drawer and revealed two slender bones—one golden eagle, one hawk—pierced and polished, flutes waiting in perfect silence.

Music has framed my life since I was four in Madrid: first as a hobby, then as devotion, from my early passion for Romantic music to the shimmering modernism of Debussy, whose Masques I played at fifteen beneath the stone arches of Dubrovnik’s Rector’s Palace. Yet nothing in my previous musical experience had prepared me for the quiet authority of these flutes. Their accession records were almost empty, their makers unnamed, but the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer of Jemez Pueblo had granted permission for their study. Phillips Academy’s Abbot Independent Scholar program let me transform my curiosity into a full-term research project under the supervision of Dr. Schultz and Dr. Elizabeth Aureden from the music department.

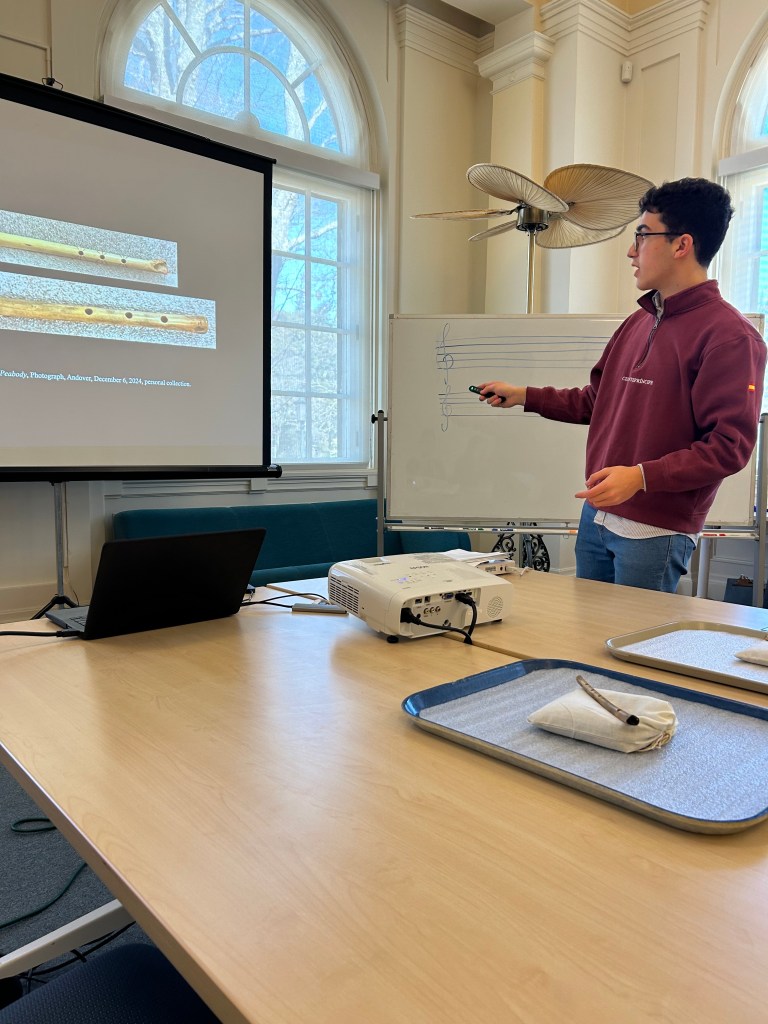

The work began with patient looking. The eagle bone flute—just under twenty centimeters—bears four clean finger-holes; the hawk bone flute is shorter, its stops conical and ringed by three tiny oblique grooves. My initial efforts left me frustrated—despite my solid musical background, I couldn’t answer any of my research questions. Guided by Indigenous scholars, I began to understand the silence and endless questions as a wise teacher. By combining archival materials with present-day Indigenous resources, chiefly from Jemez musician Marlon Magdalena, I built a relationship with the eagle bone flute and experienced the music as something much deeper than pure sound.

In his song “Eagle’s Blessings,” which I shared during my presentation to the Massachusetts Archaeological Society in April, Marlon brings the flute to life. When I first heard it, I was nearing the end of my research, which had been mostly historical and archival. I had tried to learn about other Indigenous music, but this performance tied everything together. Throughout the term, I feared profaning the cultural or religious significance of the eagle bone flute. I understood its sacredness, and as a religious person involved in interfaith activities, I recognize the importance of respecting religious artifacts.

Marlon’s explanation before he played brought everything into focus. He explained that eagle bones are sacred, held only by tribal members and used to lift prayers skyward. When he played, I felt how, through his breath, he gave life back to the eagle and honored her. Suddenly, the silence became understandable. Even though I could not draw solid scientific conclusions, I forged a connection I will never forget.

This project has awakened a passion for ethnomusicology that I am now exploring with the music department, under the guidance of Ms. Ángela Varo-Moreno, studying the presence of LGBTQ+ subcultures in techno music. I would like to end by thanking everyone at the Peabody, at Phillips Academy Andover, and at Pecos and Jemez Pueblos—and other Indigenous communities—who have safeguarded the knowledge that reached me and made this project possible. It has been a gift I will always keep in my heart.