Contributed by Marla Taylor

In fall 2013 the Peabody launched Adopt A Drawer, which connects supporters with our collections. Each gift of $1,000 supports the complete cataloging of one artifact storage drawer. Participants receive an Adopt A Drawer t-shirt, updates on cataloging, and their support is acknowledged with a name plaque and in our online catalog, PastPerfect.

Cataloging the adopted drawers is a time-consuming but rewarding task. Each drawer is selected with care to identify areas of the collection that need a little extra TLC. Often times, I don’t even know what I am going to find in the drawer!

The drawer that I am currently working on has taken quite some time. There are over 130 artifacts – mostly stone tools – from at least 13 different sites across France. Many of them are from cave sites of the Magdalenian era (10,000 – 17,000 years ago), but some of these blades, scrapers, and cores date as far back as 70,000 years old. Some of these tools could have been crafted by the hands of Neanderthals.

When I first began work on the drawer, the tools were piled on top of one another in several smaller boxes. This poor storage can easily lead to damage along the delicately crafted edges of these tools. It was in need of a major upgrade!

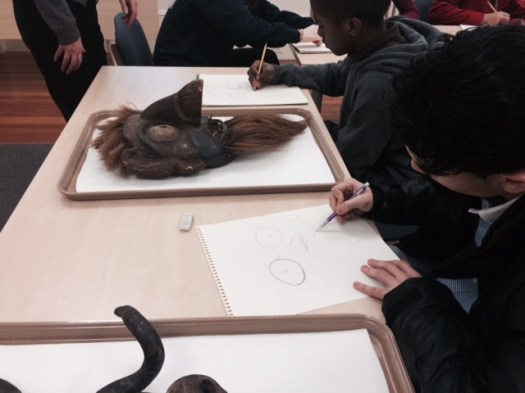

With the help of work duty students – I couldn’t do this without them! – each artifact was photographed, measured, and rehoused. I have researched each artifact in our original accession ledgers for location and collection information. These records have then been combined with notes provided by Kathleen Sterling and Sebastien Lacombe of Binghampton University and experts in the lithic technology of France’s Upper Paleolithic who visited the collection in May 2015. I am integrating all of this information into their catalog records and the adoption process is nearly complete.

I will soon share details of the contents of this drawer with its donor and you can access it too by exploring our collection online.

For additional information how to adopt a drawer watch our short video or visit our website.

Join the Peabody and the Gene Winter Chapter of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society for a night highlighting student work and research. Three groups of students will present their research ranging from historic preservation to 3D printing artifacts to 19th century portrayals of Native Americans.

Join the Peabody and the Gene Winter Chapter of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society for a night highlighting student work and research. Three groups of students will present their research ranging from historic preservation to 3D printing artifacts to 19th century portrayals of Native Americans.