Contributed by Marla Taylor and John Bergman-McCool

Every museum is full of stories and story-tellers. Our recent work in the inventory process has uncovered an old story that always gets my attention (Marla’s). But, before I begin, I must give credit to Eugene Winter, the Peabody’s late Curator Emeritus, who was a story-teller extraordinaire – I am sharing a shortened version of his memories. (Another time, I will tell you about the time Gene cooked his lunch in an active volcano or walked on a whale. The man was full of stories!)

In 1986, Gene welcomed a man named George McLaughlin into the Peabody. McLaughlin claimed to be creating a handbook on archaeology for the local Boy Scouts and was looking to photograph objects in the Peabody’s collection. As a teacher himself, Gene was happy to encourage this project and made arrangements for McLaughlin to return a couple weeks later to access the collection.

However, McLaughlin instead returned the next day and told the administrative assistant, Betty Steinert, that Gene had authorized him to examine the collection – alone. Over the next three days, McLaughlin helped himself to an unknown number of objects from the collection.

Less than a week later, Gene received a call from security at Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. A man matching McLaughlin’s description had stolen artifacts from a grad student’s work area and ran out of the museum before he could be caught. Because McLaughlin had now crossed state lines, the FBI became involved.

Gene and Betty remembered that McLaughlin had used the Peabody’s phone to call his wife about being late for dinner. This crucial piece of information allowed the FBI to locate McLaughlin’s home. Fortunately, McLaughlin was arrested soon after these incidents and all materials in his possession were seized.

In total, McLaughlin victimized six institutions in New England and stole thousands of artifacts valued at over $800,000 in 1986 ($1.9 million in 2020 dollars). He intermingled the artifacts based on his own system and systematically removed their catalog numbers (often the best clue to their original home). By so drastically removing the objects from their context, it was a challenge to return the objects to their appropriate homes.

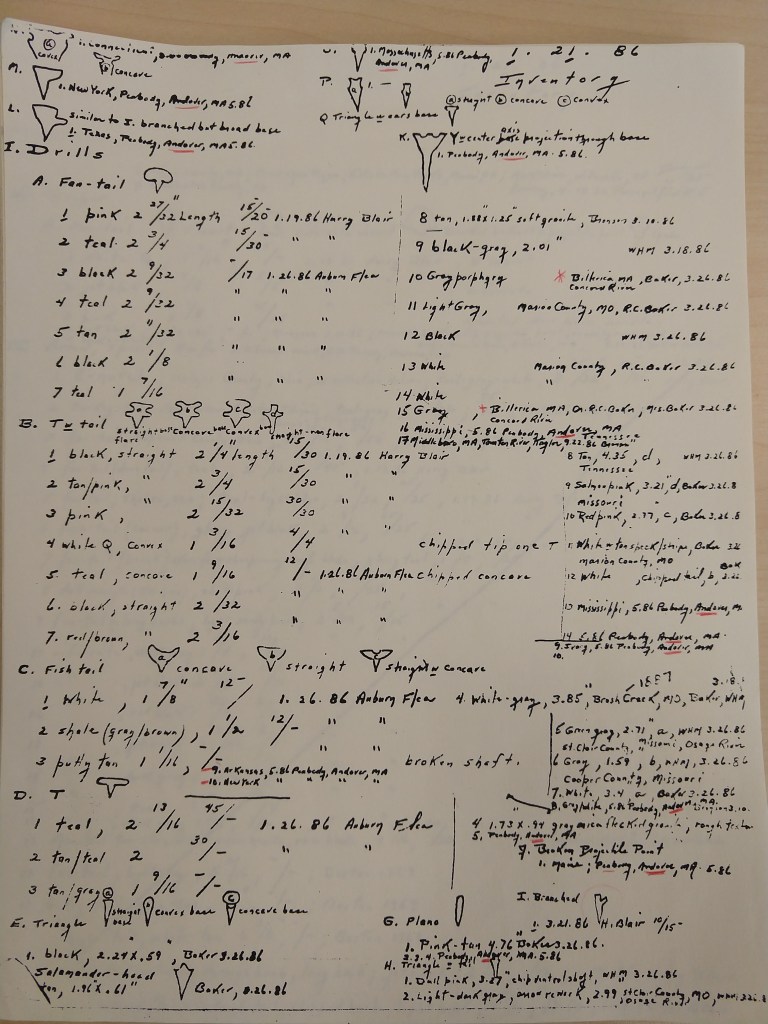

McLaughlin had kept his own version of a ledger identifying the objects and where they came from. And fortunately, Gene was able to recognize a dozen or so very specific objects from the Peabody’s collection. The FBI left it up to the victimized institutions to divide the material in McLaughlin’s collection. The Peabody ended up with nearly 1600 objects from McLaughlin.

Ultimately, McLaughlin was sentenced to a three year suspended sentence and four years of probation. He was also fined $10,000 and ordered to pay a small restitution to each institution.

And therein lays the origin of the Peabody’s FBI collection.

Having come across these materials during our inventory and rehousing project it was time for them to be cataloged by myself (John). One challenge confronted us: McLaughlin had removed any identifying numbers applied by the museums and applied stickers with his own numbers. As the objects were cataloged, a careful inspection was made for remnants of original numbers not completely obliterated during the removal process. There were many with tantalizing hints of legible numbers. In the end though, there were just a few objects with numbers clear enough to associate with our museum’s ledger.

The remaining majority of objects needed new numbers. As mentioned above, McLaughlin had organized the objects and transcribed them into a ledger of sorts. His ledger was too general to make a one-to-one comparison with our own museum’s ledger, but it served as the outline of our numbering system. We added our own prefix, indicating that these objects were stolen and returned by the FBI and followed that with the McLaughlin number. In that way the objects will always carry that part of their strange history.

I (Marla again) do want to note that to our knowledge, McLaughlin is not responsible for the missing artifacts from Etowah and Little Egypt discussed in our blog in 2019.