Contributed by Emma Lavoie

As the school year comes to a close and we take time to slow down (thank you vacation time), what better time this season then to grab a book and settle down on a porch swing. It’s time to grab your library card, load up your Kindle, or get yourself to your local bookstore. Our staff and friends of the Peabody have done it again… Back by popular demand! The Peabody shares their favorite finds for this summer’s reading list. We even threw in a podcast as a bonus for any listeners! We hope you have a wonderful summer dear readers and enjoy exploring these “Peabody Picks.”

Happy reading!

The Rose Code by Kate Quinn – Recommended by Emma Lavoie, Administrative Assistant

If you read one historical fiction book this year, THIS SHOULD BE IT! As England prepares for World War II, three women from very different walks of life answer the call to mysterious county estate Bletchley Park, where the best minds in Britain train to break German military codes. Osla translates decoded enemy secrets, Mab works the legendary code-breaking machines, and Beth is one of the Park’s few female cryptanalysts. Eventually war, loss, and the impossible pressure of secrecy will tear the three apart. Flash forward seven years later, these friends-turned-enemies are reunited by a mysterious encrypted letter – the key to which lies buried in the long-ago betrayal that destroyed their friendship and left one of them confined to an asylum. A mysterious traitor has emerged from the shadows of their Bletchley Park past, and now Osla, Mab, and Beth must resurrect their old alliance and crack one last code together against the backdrop of the royal wedding of Elizabeth and Philip.

“The reigning queen of historical fiction.” – Fiona Davis, New York Times bestselling author of The Lions of Fifth Avenue

Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann – Recommended by Michael Agostino, Peabody Volunteer

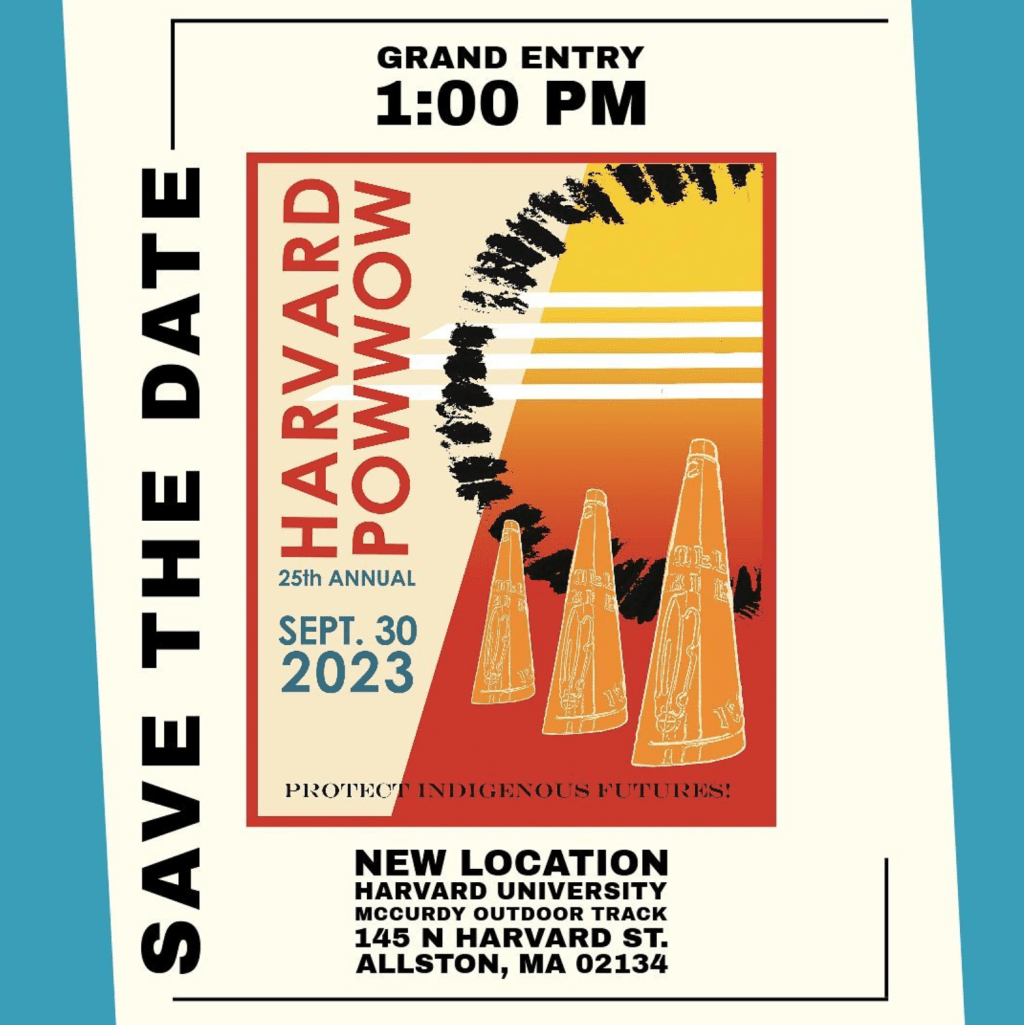

Set in the 1920s, this book features people of the Osage Nation who were relocated to barren lands in Oklahoma which were later discovered to be rich in oil. Per capita, members of the Osage nation quickly became the richest people in the world and targets for murder. This book carefully describes efforts by lawmen to solve these crimes and bring the murderers to justice. The lawmen were led by J. Edgar Hoover and his organization soon became the FBI – in what became one of the organization’s first major homicide investigations. Together with the Osage and Texas Ranger, Tom White, they began to expose one of the most sinister conspiracies in American History. A true-life murder mystery about one of the most monstrous crimes in American history, Killers of the Flower Moon, is highly acclaimed, receiving numerous awards, and was recently made into a movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert Deniro.

“A masterful work of literary journalism crafted with the urgency of a mystery…. Contained within Grann’s mesmerizing storytelling lies something more than a brisk, satisfying read. Killers of the Flower Moon offers up the Osage killings as emblematic of America’s relationship with its indigenous peoples and the ‘culture of killing’ that has forever marred that tie.” – The Boston Globe

Swords and Deviltry (Fafhrd & the Gray Mouser #1) by Fritz Leiber – Recommended by Ryan Wheeler, Peabody Director

First in the influential fan-favorite series, Swords and Deviltry collects four fantastical adventure stories from Fritz Leiber, the author who coined the phrase “sword and sorcery” and helped birth an entire genre. This collection of short stories and novellas follows the adventures of barbarian Fafhrd and conjurer turned sword fighter Gray Mouser written by Leiber in the 1950s and 60s and collected in 1970. If you like Robert E. Howard and Conan the Barbarian, you will love this! And if you do, there are a total of seven of these collected volumes chronicling the exploits of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, in this and other dimensions.

“A Grand Master of Science Fiction and Fantasy.” – Science Fiction Writers of America

A Gentlemen in Moscow by Amor Towles – Recommended by Richard Davis, Peabody Volunteer

In 1922, Count Alexander Rostov is deemed an unrepentant aristocrat by a Bolshevik tribunal, and is sentenced to house arrest in the Metropol, a grand hotel across the street from the Kremlin. Rostov, an indomitable man of erudition and wit, has never worked a day in his life, and must now live in an attic room while some of the most tumultuous decades in Russian history are unfolding outside the hotel’s doors. Unexpectedly, his reduced circumstances provide him entry into a much larger world of emotional discovery. Brimming with humor, a glittering cast of characters, and one beautifully rendered scene after another, this singular novel casts a spell as it relates the count’s endeavor to gain a deeper understanding of what it means to be a man of purpose.

“How delightful that in an era as crude as ours this finely composed novel stretched out with old-World elegance.” – The Washington Post

Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo – Recommended by Marla Taylor, Curator of Collections

Galaxy “Alex” Stern is the most unlikely member of Yale’s freshman class. Alex dropped out of school early and into a world of dead-end jobs and much, much worse. In fact, by age twenty, she is the sole survivor of a horrific, unsolved multiple homicide. Some might say she’s thrown her life away, but Alex is offered a second chance: to attend one of the world’s most prestigious universities on a full ride. What’s the catch, and why her? Still searching for answers, Alex arrives in New Haven tasked by her mysterious benefactors with monitoring the activities of Yale’s secret societies. Their eight windowless “tombs” are the well-known haunts of the rich and powerful, from high-ranking politicos to Wall Street’s biggest players. But their occult activities are more sinister and more extraordinary than any paranoid imagination might conceive. They tamper with forbidden magic. They raise the dead. And, sometimes, they prey on the living.

“The best fantasy novel I’ve read in years, because it’s about real people. Bardugo’s imaginative reach is brilliant, and this story – full of shocks and twists – is impossible to put down.” – Stephen King

The Last Thing He Told Me by Laura Dave – Recommended by Beth Parsons, Office of Academy Resources, Director for Museums and Educational Outreach

Before Owen Michaels disappears, he manages to smuggle a note to his beloved wife of one year: Protect her. Despite her confusion and fear, Hannah Hall knows exactly to whom the note refers: Owen’s sixteen-year-old daughter, Bailey. Bailey, who lost her mother tragically as a child. Bailey, who wants absolutely nothing to do with her new stepmother. As Hannah’s increasingly desperate calls to Owen go unanswered; as the FBI arrests Owen’s boss; as a US Marshal and FBI agents arrive at her Sausalito home unannounced, Hannah quickly realizes her husband isn’t who he said he was. And that Bailey just may hold the key to figuring out Owen’s true identity—and why he really disappeared. Hannah and Bailey set out to discover the truth, together. But as they start putting together the pieces of Owen’s past, they soon realize they are also building a new future. One neither Hannah nor Bailey could have anticipated.

“In this novel, now an Apple TV+ series, Laura Dave has given readers what they crave most – a thoroughly engrossing yet comforting distraction.” – BookPage

Leviathan Wakes by James A. Corey – Recommended by Nick Andrusin, Temporary Educator and Collections Assistant

Humanity has colonized the solar system—Mars, the Moon, the Asteroid Belt and beyond—but the stars are still out of our reach. Jim Holden is XO of an ice miner making runs from the rings of Saturn to the mining stations of the Belt. When he and his crew stumble upon a derelict ship, the Scopuli, they find themselves in possession of a secret they never wanted. A secret that someone is willing to kill for—and kill on a scale unfathomable to Jim and his crew. War is brewing in the system unless he can find out who left the ship and why. Detective Miller is looking for a girl. One girl in a system of billions, but her parents have money and money talks. When the trail leads him to the Scopuli and rebel sympathizer Holden, he realizes that this girl may be the key to everything. Holden and Miller must thread the needle between the Earth government, the Outer Planet revolutionaries, and secretive corporations—and the odds are against them. But out in the Belt, the rules are different, and one small ship can change the fate of the universe. Also now a Prime Original TV Series called The Expanse.

“This is the future the way it was supposed to be.” – The Wall Street Journal

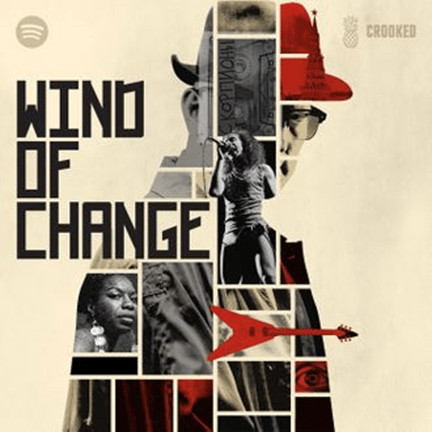

Wind of Change Podcast by Pineapple Street Studios and Crooked Media – Recommended by John Bergman-McCool, Collections Assistant

It’s 1990. The Berlin Wall has just come down. The Soviet Union is on the verge of collapse. A heavy metal band from West Germany, the Scorpions, releases a power ballad, “Wind of Change.” The song becomes the soundtrack to the peaceful revolution sweeping Europe – and one of the biggest rock singles ever. According to some fans, it’s the song that ended the Cold War. Decades later, New Yorker writer (and podcast host) Patrick Radden Keefe hears a rumor from a source: the Scorpions didn’t actually write “Wind of Change.” The CIA did. This is Patrick’s journey to find the truth. Among former operatives and leather-clad rockers, from Moscow to Kyiv to a GI Joe convention in Ohio, It’s a story about spies doing the unthinkable, about propaganda hidden in pop music, and a maze of government secrets.

“Wind of Change is a beautifully constructed listen, never less than entertaining.” – The Guardian