Contributed by Emma Cook

My name is Emma Cook, I am the Administrative Assistant at the Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology. I have a background in archaeology, history, and museum studies with undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University of Georgia and Tufts University. Aside from my administration duties, I work with the Peabody’s collections. Recently I’ve been involved in the Inventory and Rehousing Project and I am working with collections on the first floor South Alcove, located in one of our gallery/classroom spaces.

The Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology collection comprises nearly 600,000 artifacts, photographs, and archives. Some of these materials are displayed and used for teaching, while many reside in our collection storage. What is unique about much of our collection space is its original storage. The bays and drawers in which many of these artifacts inhabit are almost as old as the Peabody itself, the bays being first built in the early 1920s. However, below the surface of these pine wood bays and drawers are a collection of uncatalogued objects that have hardly come to light (literally), with some still stored in the tin foil and paper bags they were placed in upon archaeological excavation many years ago.

The antiquated charm of these wooden bays is not enough to meet the need of accessible storage for our collections and the goal is to replace them with new custom-built shelves. In preparation of this storage renovation, objects need to be identified, catalogued, and rehoused. This work is completed through our Inventory and Rehousing Project.

I began my work simply inventorying the objects in each drawer of each bay in the alcove. Some of these objects were already identified, numbered, and recorded in Past Perfect – a museum software that is the standard for cataloguing museum collections. Through this software, the Peabody collection is documented and made accessible online. My job was to make sure these objects were accounted for and in the right place, as well as properly rehoused and organized within the drawers. Sounds pretty easy right? Well, eventually things changed as I came across several drawers and bays containing objects with old numbers or no numbers at all. This is where my cataloguing efforts began.

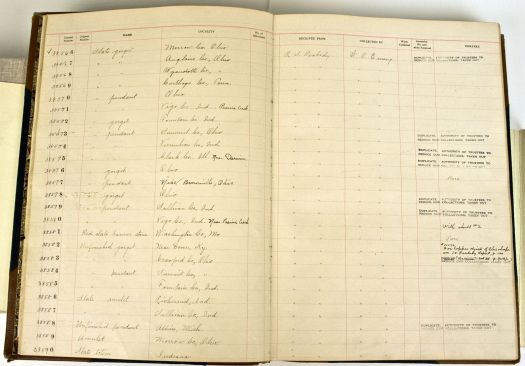

Cataloguing is the process of recording details about an object into a collection catalog or database that documents the information of each object as well as its location in storage. Through this process each object receives a unique number. This number is physically attached to the object and appears in records related to the object in Past Perfect. In museums and archives, objects or materials in a collection are normally catalogued in what is called a collection catalog. In the past, this was traditionally done using a card index, but in the present-day it is normally implemented using a computerized database – for the Peabody this is Past Perfect. Some of the objects I came across with “old numbers” were either connected to the Peabody’s past card index cataloguing system or the Peabody’s original numbering system (i.e. 1,2,3,…. 78,049).

Each object was given a new number associated with the Peabody’s present catalog numbering sequence (i.e. 2019.1.123). This numbering sequence is a three-part number, making it both simple and expandable. The first part of the sequence is the year in which the object was accessioned or catalogued (i.e. 2019). The second part of the sequence is given to objects in chronological order based on when they were first accessioned (i.e. 2019.1). The third part of the sequence gives a single object a number in chronological order (i.e. 2019.1.1). Objects that had an affixed label had the new number written on the label. Objects without labels had their numbers painted on with ink. A solution called B72 is applied to the object before the ink in order to protect the original surface of each object. This solution is not harmful to the object and can be easily removed if a mistake is made or the object needs a different number.

The cataloguing process is not an easy one, nor is inventorying and rehousing a collection. The process may be slow and tedious, but it does have its rewards. By using a great deal of care, time, and effort, rehoused and identified objects can be used for teaching and research. Not only can collection staff have full access to the collection, they can provide a safe and accessible place for these materials in storage. The cataloguing process may seem like a trivial task, but it just goes to show – it’s more than a number.

For more information and reading on the Inventory and Rehousing Project, see the following blogs below:

Transcribing the Collection – January 2019

A New Face in the Basement – January 2019

Ceramic Inventory Complete – December 2018

Collections Reboxing Project Update – April 2018

A Day in the Life of Boxing Boxes – November 2017

Shelving to the Rescue – September 2016

Boxes and Boxes and Boxes – August 2016

Summer Work Duty Students Begin Rehousing Inventory – August 2016