Contributed by Emma Lavoie

The change in season brings a time for storytelling and passing down traditions. The winter months are a prime time for sharing scary stories due to colder weather keeping people inside and gathered together.

In honor of Indigenous Peoples’ Day (October 14) and upcoming National Native American Heritage Month (November), we’re highlighting some folklore inspired by the Indigenous dark fiction anthology, Never Whistle at Night. This book is comprised of 26 short stories that explore aspects of Indigenous horror, beliefs, traditions, and folklore. These stories are told by a variety of Indigenous authors (see complete list below), edited by Shane Hawk (Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma) and Theodore C. Van Alst Jr. (Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians), and introduced by Stephen Graham Jones (Blackfeet Nation).

Contributing Authors

Norris Black (Haudenosaunee, Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory)

Amber Blaeser-Wardzala (White Earth Nation)

Phoenix Boudreau (Chochenyo)

Cherie Dimaline (Métis Nation of Ontario)

Carson Faust (Edisto Natchez-Kusso Tribe of South Carolina)

Kelli Jo Ford (Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma)

Kate Hart (Chickasaw/Choctaw in Arkansas)

Shane Hawk (Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma)

Brandon Hobson (Cherokee Nation Tribe of Oklahoma)

Darcie Little Badger (Lipan Apache Tribe of Texas)

Conley Lyons (Comanche)

Nick Medina (Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana)

Tiffany Morris (Mi’kmaw)

Tommy Orange (Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma)

Mona Susan Power (Standing Rock Sioux Tribe)

Marcie R. Rendon (White Earth Band of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe)

Waubgeshig Rice (Wasauksing First Nation)

Rebecca Roanhorse (Navajo Nation)

Andrea L. Rogers (Cherokee Nation)

Morgan Talty (Penobscot Indian Nation)

D.H. Trujillo (Pueblo)

Theodore C. Van Alst Jr. (Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians)

Richard Van Camp (Dene Nation)

David Heska Wanbli Weiden (Lakota)

Royce Young Wolf (Hiraacá, Nu’eta, and Sosore, ancestral Apsáalooke and Nʉmʉnʉʉ)

Mathilda Zeller (Inuit)

The title of the anthology refers to a belief common in many Indigenous cultures that whistling at night can attract malevolent entities. The act of night whistling is forbidden by many Native American cultures due to a shape-shifting entity, known as a “Skinwalker” or “Stekini” that responds to the call, causing harm to those who encounter it.

Native cultures use storytelling to pass down knowledge and history, including folklore. Scary stories often carry deeper meanings, serving as lessons and warnings. Some of my favorite stories from this book were: Kushtuka, Quantum, Snakes are Born in the Dark, Before I Go, and Dead Owls.

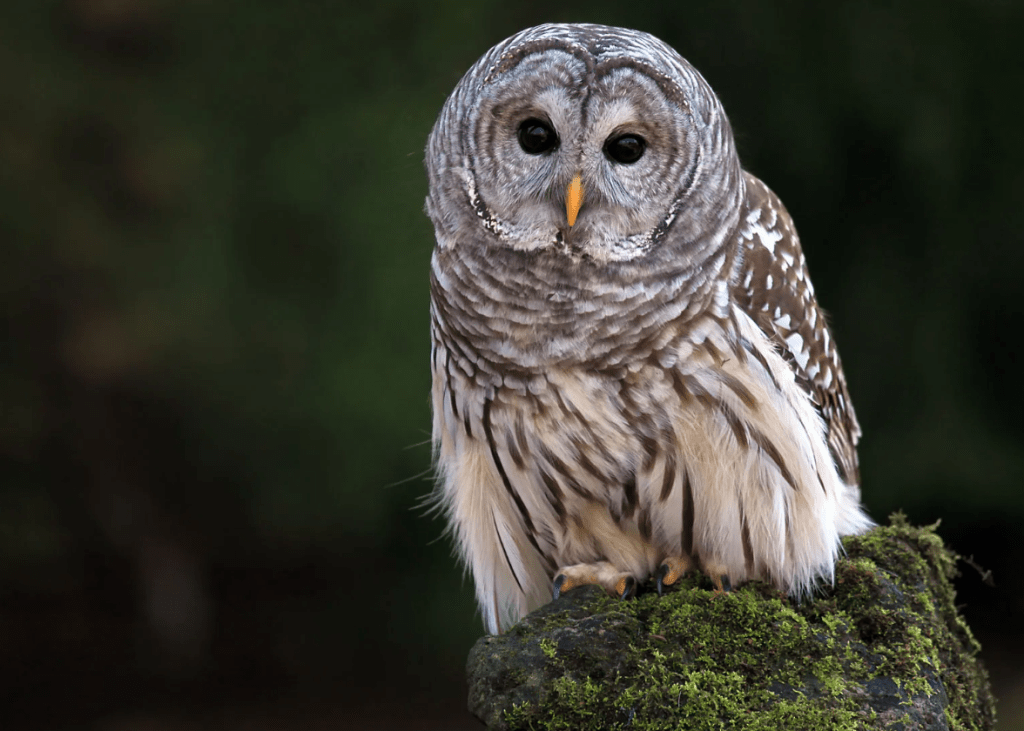

Several stories in the book share a common subject – the owl. Interpretations of owls can be found across different Native American tribes, with some viewing owls more negatively than others. There are several items in the Peabody collection that highlight the owl form, their meanings varying significantly between different Indigenous cultures and locations. Here are just a few for you to explore!

Owls are often associated with death and the spirit world, seen as messengers or harbingers of bad luck reflected in their nocturnal habits. Seeing an owl, particularly during the day can be a sign of death or misfortune. Some tribes consider owls as spirits of the deceased or that they might not be real birds at all, but shapeshifters. The sound of an owl’s hoot is seen as a call to the spirit world or a way to connect with ancestors.

Owl Effigy (2018.2.1266) – Fragment of an owl effigy from the Valley of Mexico. Warren K. Moorehead compared this item to clay effigies from the Etowah village site in his 1932 book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah Site in Georgia.

Folklore of the Valley of Mexico believe in a witch known as “La Lechuza” who shapeshifts in the form of an owl that preys on people who are disobedient, unbaptized, or who harm others. Check out this episode on La Lechuza from the podcast, History Uncovered.

Owl Effigy Slingshot (97.1.53) – From the Ixil Maya community in Chajul, El Quiché, Guatemala. Used by men and boys to hunt birds, though it is common to hunt with a blowgun.

Other tribal beliefs revere owls as symbols of wisdom and intuition, as well as carriers of ancient knowledge and protection.

Ceramic Owl Figurine (2017.6.1) – Ceramic piece by Maxine Toya from the Pueblo of Jemez, New Mexico. In Pueblo culture, owls are seen as protectors. The ceramic owl design is built by stacking and smoothing hand coils of clay. The piece is both carved and painted, the feathers on the front being carved into the clay. Painted designs are intricate using symbols of rain, clouds, and feathers. These designs are all matte and painted with clay slips with only the eyes being polished.

Maxine Toya is well known for her figurative pottery (the first piece of pottery Maxine created was an owl!) Maxine is one of several pottery artists from the Pueblo of Jemez that visit Phillips Academy campus each spring to work with students in ceramic classes. You can read more about these visits here and here!

Ceramic Owl Effigy Jar (90.4.2) – Globular body in black on white design with vessel opening located at owl beak. Owl facial features at neck, wings at sides and tail at back. The globular shape is the most recognizable characteristic of pottery from Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico.

Owls are featured in Cochiti Pueblo pottery, often associated with the god of death and spirit of fertility, Skeleton Man.

Exciting News! – Never Whistle at Night, Part II: Back for Blood is currently accepting submissions from emerging Indigenous writers. This is the second book in the Never Whistle at Night series.