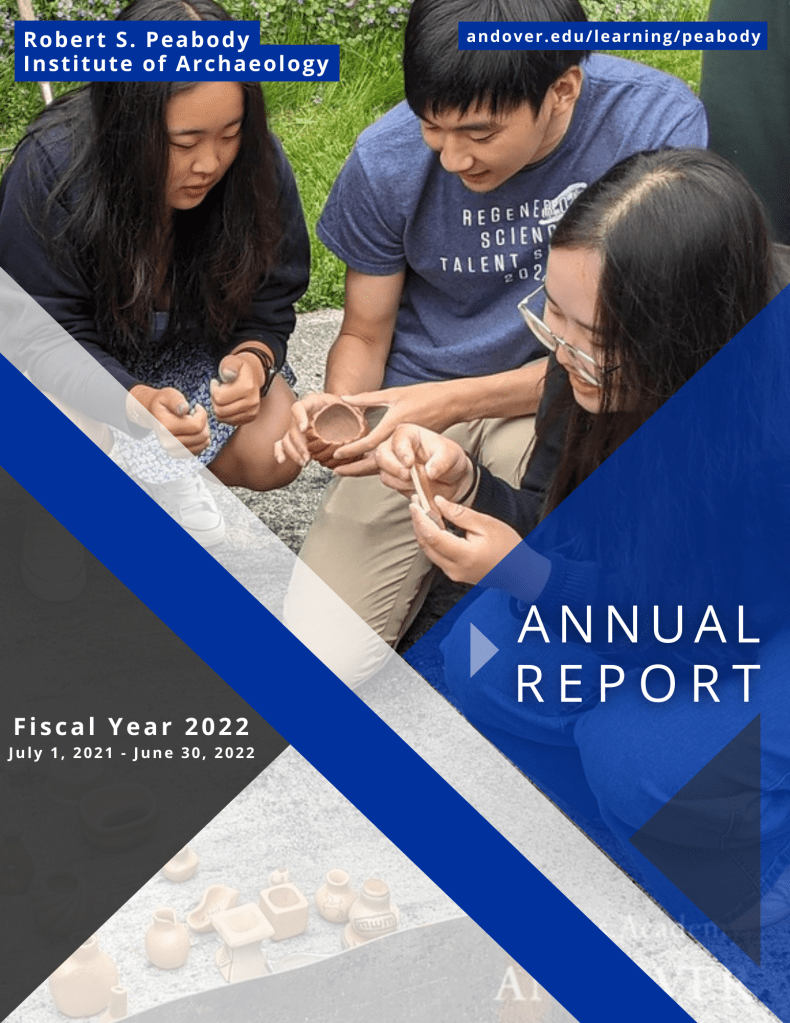

Contributed by Emma Lavoie

Ever wonder what lies behind a photograph? Beyond the simple description scrawled on the back of each image? The Peabody collection contains more than 600,000 artifacts, photographs, and documents. The Peabody’s photograph collection, specifically, is extensive and contains many interesting, yet untold stories. To bring these stories and photographs to light, we would like to share them with YOU, fellow readers, in our blog series, Behind the Photograph. You can find these stories using our BehindThePhoto tag on our blog.

The Mural

As the Peabody enters the pre-construction phase of a much-needed renovation project, I’ve been looking back at some of our old photos of the building. This image in particular is fascinating, as it was taken during the installation of the Peabody’s Stuart Travis mural in 1938. Those of you who have visited the Peabody may find the room in this image familiar – it’s the interior of our front entrance door! Although those columns behind the mural have since been removed, the crown molding, floor, and archways are still present at the Peabody today. Around the perimeter of the image you’ll find what looks to be an old grandfather clock against the wall to the left. If you peer closely just through both archways (to the right and left) you’ll see glimpses of exhibit cases where the Peabody’s first floor galleries housed exhibits and displayed artifacts.

The Peabody’s mural was created by American artist, illustrator, and designer, Stuart Travis (1868-1942). Stuart Travis is well-known to the Phillips Academy Andover community. Not only can you find his work at the Peabody, but all over – the Oliver Wendell Holmes Library, Paresky Commons, the Gelb science building, and the wrought iron gate at the entrance to the Moncrieff Cochran Bird Sanctuary. Stuart Travis is buried in the Chapel Cemetery here on campus.

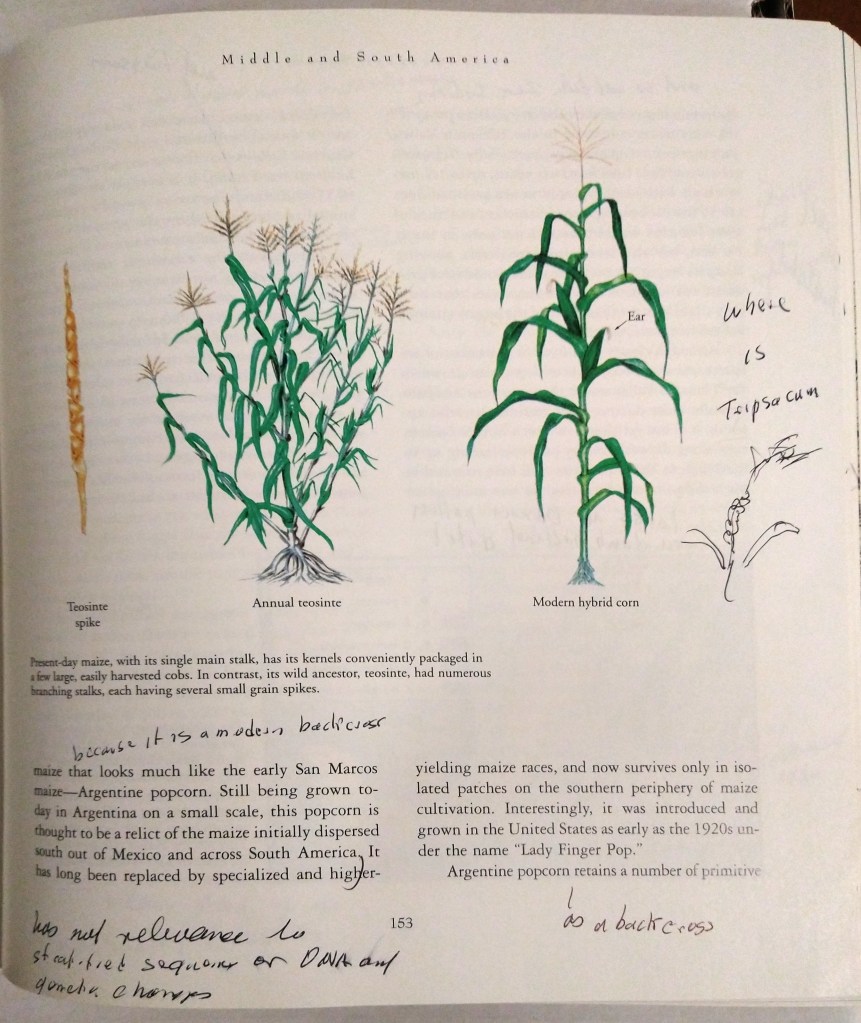

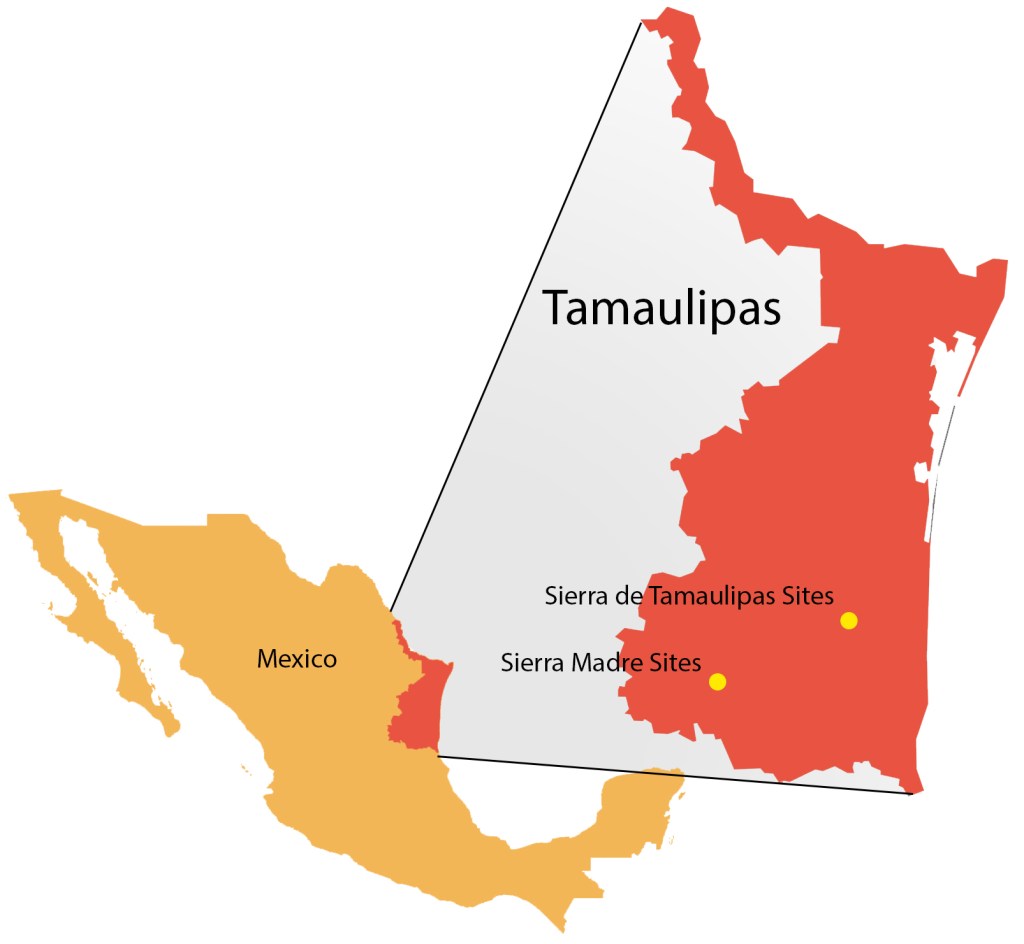

The mural was installed in the Peabody’s central staircase where it continues to reside today. Titled “Culture Areas of North America,” this mural reflects ideas about anthropology and archaeology in the 1930s and 1940s. The mural features many drawings of artifacts from various sites and museum collections, some drawings even link to archaeological works by long-time Peabody Director, Warren K. Moorehead (1924-1938) as well as Director, Douglas Byers (1938-1968) and Curator, Fred Johnson (1936-1968).

The mural was dated 1938, however, Stuart Travis continued to make additions through 1942. The mural was later restored in 1997 by Christy Cunningham-Adams through the generous support of the Abbot Academy Fund. If you look closely at the image, you’ll see the mural was created in sections (i.e. the very fine line located down the middle of the mural). One interesting detail you cannot see from the photo, but rather in person is the various pencil notes and markings that still remain on the mural. This leads me to believe that perhaps the mural was never quite finished or rather, some new additions planned for the mural never came to fruition.

For more information about the Peabody’s Stuart Travis mural, check out this blog by Peabody Director, Ryan Wheeler – Culture Areas of North America: The Peabody’s Stuart Travis Mural.

Another fascinating find and story is this blog from our past temporary archivist, Irene Gates, who discovered six small notebooks belonging to Stuart Travis depicting illustrations and information about the Indigenous communities represented in the mural.

The Film

Mural history aside, the material image itself has quite the hazardous history (or should we say fiery?) The original image of the mural installation was made on a nitrate negative, a type of film used as a base for photographic roll film created by George Eastman in 1889. Nitrate was used for photographic and professional 35mm motion picture film until the 1950s.

What many may (or may not) know is nitrate film is highly flammable and also toxic when decomposing with age. New nitrate film could ignite with the heat of a cigarette, while decomposing nitrate film can ignite spontaneously at temperatures as low as 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Once ignited, nitrate film burns rapidly, fueled by its own oxygen, and releasing toxic fumes.

Before you jump to thoughts of flammable film spontaneously combusting in the Peabody’s collections, let me assure you THERE IS NO nitrate film currently located at the Peabody. But at one point in time there used to be nitrate film in the Peabody’s archival photograph collection, YIKES! As of July 2010, all nitrate negatives were digitized and then discarded due to the film’s potential hazard to the Peabody collections and building.

With that out of the way, let’s dive in to the history of nitrate film and how much of this history went up in smoke. We see its legacy in Alfred Hitchcock’s Sabotage – a bus operator tells a young boy he cannot bring two reels of nitrate film onboard, it’s flammable after all. Then in Quentin Taratino’s Inglourious Basterds – nitrate film’s volatile chemistry is used for his alternate history story of a plot to assassinate high-ranking officials of the Nazi party, including Hitler.

Nitrate fires were infrequent compared to the rapid spread of cinema, however, when disaster occurred at the hands of nitrate film, the results were quite devastating. One such fire occurred at Paris’s 1897 Charity Bazaar, claiming 126 lives many of which were women. In 2019, a French drama miniseries debuted on Netflix called Le Bazar de la Charité (The Bonfire of Destiny) depicting this destructive time in history.

The 1940s saw numerous fires in New York City involving nitrate film. Investigators found no evidence of negligence by personnel or the careless use of cigarettes. In fact, it appeared the nitrate film spontaneously ignited due to abnormally hot summers. Since burning nitrate produces its own oxygen, submerging the film in water is futile. In addition, the fumes given off by its ignition are highly toxic and hamper any efforts to suppress the fire. These fumes contain oxides of nitrogen which, if inhaled, can be fatal. Unfortunately, nitrate film must burn itself out.

Besides its combustive properties, nitrate is extremely fragile. Overtime, the film naturally shrinks and deteriorates, even when treated with care. Film archivists in the 1970s and 80s expressed urgency for the preservation of nitrate film using the slogan, “Nitrate Won’t Wait,” with images of the destruction of vault fires such as the 1978 vault fire at the National Archives and Records Service in Suitland, Maryland, which destroyed 12.6 million feet of historical newsreel footage and outtakes donated by Universal Pictures. As a result of this, many nitrate negatives and film have been digitized or reprinted on polyester stock (the replacement to nitrate beginning in the 1950s).

How to Spot Decomposition in Nitrate Film (sourced from the Science & Media Museum Blog)

1.) Fading picture with amber discoloration

2.) Film becomes brittle; emulsion becomes adhesive and film sticks together

(At stages 1 and 2, film can be copied)

3.) Film has a noxious odor

(At stage 3 some parts of the film may be copied)

4.) Film is soft and covered with a viscous froth

5.) Film is deteriorating into a brownish acrid powder

(At stages 4 and 5, film should be immediately destroyed by local fire department)

On the other side of the argument, many believe nitrate film is a viable artifact that doesn’t have to be destroyed or hidden away. In 2015, the Nitrate Picture Show was created by the Eastman Museum to raise awareness of nitrate and preserve what remains. The Eastman Museum currently houses 24,054 reels of nitrate film.

Circling back to our mural image – I’d like to provide the current status of our Peabody mural during the pre-construction phase of our planned renovation work. We are taking protective measures to keep it safe during upcoming renovation work. Here you can see a temporary wall being placed over the mural as a protective layer.